Deaths From Doctor Shortage Fuel Election Angst in Korea

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

(Bloomberg) -- In March 2023, a 17-year-old girl who fell from a building in the South Korean city of Daegu died after her ambulance was turned away by three hospitals that lacked doctors to treat her.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Germany to Order Ships, Armored Vehicles Worth Up to €7 Billion

Iran’s Better, Stealthier Drones Are Remaking Global Warfare

Blackstone $10 Billion Deal Is Latest Bet Property Near Lows

She was among more than 3,750 patients who have died since 2017 after local hospitals refused to provide care, according to a report by Cheong Yooseok, a professor of medical science at Dankook University in Cheonan city.

The startling statistic from one of Asia’s richest countries has become a major issue in the parliamentary elections taking place on April 10. While the country won acclaim for its low fatality rate during the Covid-19 pandemic, the focus now is on inefficiency, waste and skewed economic incentives in the health-care system.

Renowned medical centers in Seoul are overwhelmed by patients, while the rest of the country struggles with a lack of physicians. A six-week-and-counting national walk-out by nearly 13,000 residents and interns protesting a plan to boost medical school enrollment has exacerbated the situation.

Seung-Pyo Jung, an esophageal cancer patient who lives on Jeju Island in south, flew to Seoul National University Bandung Hospital for surgery last June. While he’s supposed to have checkups every four weeks, sometimes it takes several months to get an appointment.

“There’s no doctor at all on this island who can treat esophageal cancer,” Jung said of his hometown, which has a population of almost 700,000 people. “Everything is so concentrated in Seoul.”

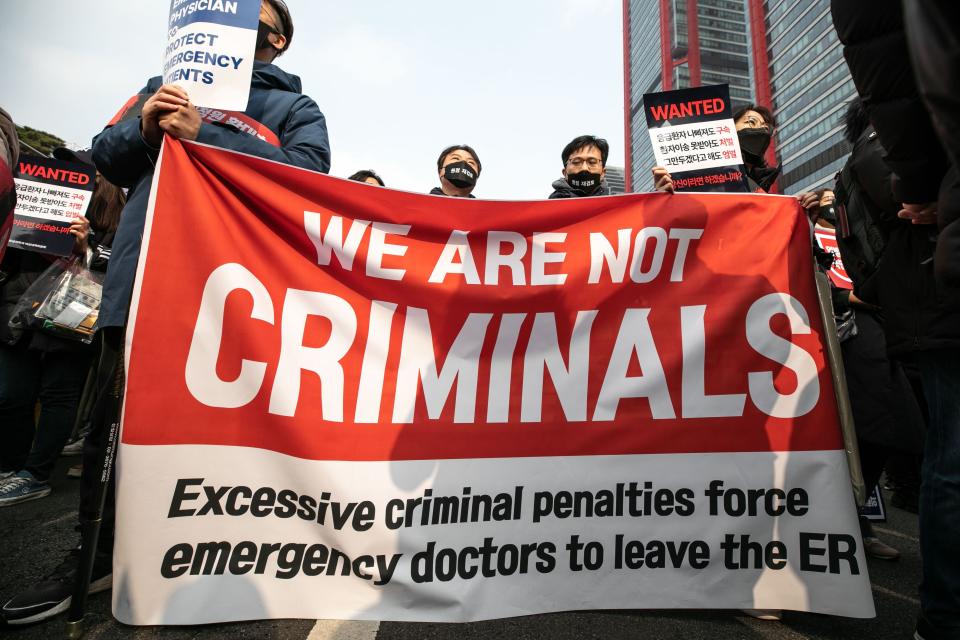

The Korean Emergency Medical Association, which advocates for doctors working at emergency centers, warned that it may join the protest. Meanwhile, the health ministry said it’s willing to discuss the Korean Medical Association’s efforts to delay the plan to increase medical school enrollment if the group has a scientific, rational and unified proposal.

Health Care Collapse

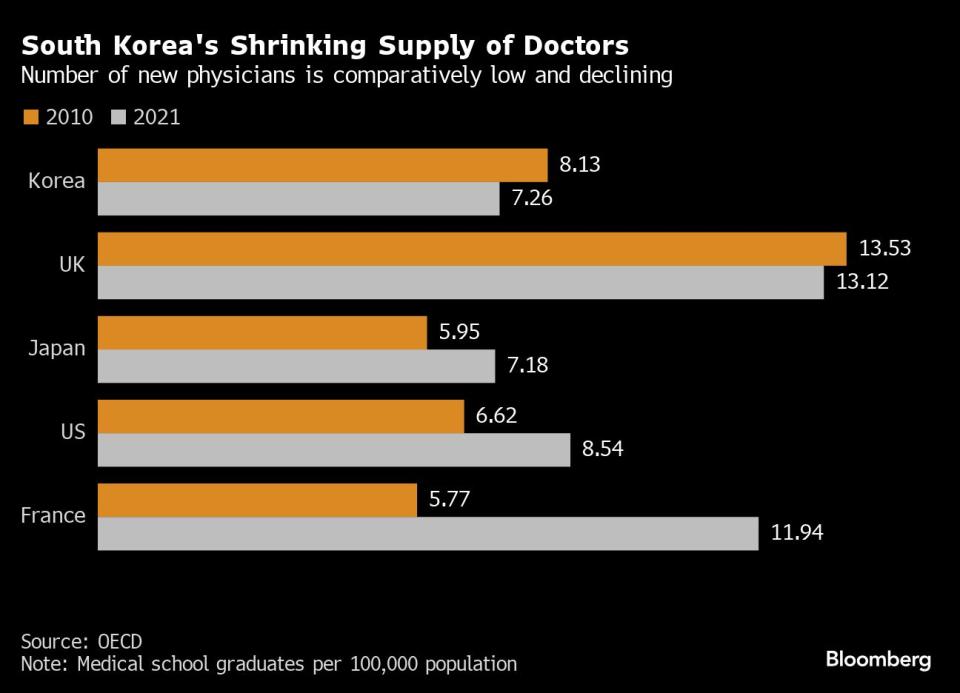

Korea has among the fewest doctors per capita of all developed countries and hasn’t increased the number of medical students in more than two decades, said Gaetan Lafortune, a senior economist at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Demographic factors like the rapidly aging population will exacerbate the scarcity, he said.

South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol has vowed to address the crisis. He proposed measures, like increasing the number of doctors, that have drawn complaints for being “populist moves” ahead of the election to select the 300 member National Assembly.

While his conservative People Power Party is currently in power, he’s trying to flip dozens of seats held by his progressive rivals, led by the Democratic Party, to take control of the national legislature.

The health-care system is “collapsing,” Yoon said at a public hearing in February. “Now is the golden time to push reforms.”

Yet the doctors themselves oppose efforts to expand physician supply, arguing that the government’s proposal to increase medical school enrollment by 2,000 spots a year from the current 3,058 doesn’t address the root problem.

This, they say, is that doctor pay in some critical fields covered by the country’s National Health Insurance system is far lower than that for outside specialists, especially those who do cosmetic and aesthetic procedures. The disparity in compensation and infrastructure between Seoul and rural areas also means a dearth of medical workers outside the capital.

Read more: Yoon Urges Korean Doctors to Return, Leaves Room for Talks

Disappearing Doctors

“Doctors are disappearing at emergency centers, surgery rooms, delivery rooms, and hospitals in smaller cities,” said Cheong, from Dankook University, in a December report. “Many young doctors gave up becoming fellows at medical colleges and work in the beauty industry.”

Cosmetic surgery has aggressively taken hold and medical tourism is booming in South Korea. More than 8 million foreign patients arrived between 2009 and 2022, many for the beauty industry that offers ubiquitous access to plastic surgery, Botox for $6 per shot, and laser skin tightening.

Meanwhile, essential fields including pediatrics have been hard hit. Only 53 residents applied to fill 205 pediatric slots for this year, and just eight were outside Seoul and its surroundings, according to the health ministry. For pediatric surgery, two trainee doctors applied for spots outside of the greater Seoul area.

In June 2023, the Korean Pediatric Society held a conference titled “How to Exit Pediatrics” focused on learning about other disciplines including cosmetic surgery. The seminar was done at the behest of members who said the country’s ultra-low birth rate made it difficult to run pediatric clinics, officials said in a television interview with Channel A.

Outside Seoul

The situation is dire in most parts of the country.

More than half of Korea’s 114,000 doctors and dentists worked in Seoul or Gyeonggi province in 2022, according to the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service.

Hiring doctors outside the capital is tough, said Cho Seung-yeon, president of Incheon Medical Center. He couldn’t find anyone to lead the dialysis division for two years. Another public hospital offered $1 million for a cardiologist, he said.

Salaried doctors at private clinics can earn in excess of $300,000 annually, while those on their own make even more, he said. Cho offers $200,000 a year for physicians at his public hospital in Incheon, but he said few ultimately come.

Even in Seoul, medical care can be tenuous given the doctor shortage.

Kim Sung Ju, a 62-year-old who underwent surgery for esophageal cancer a decade ago, undergoes a battery of tests and waits hours for a brief visit with his doctor at Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital in Gangnam, an upscale neighborhood in the city’s southeast, every three months.

“I really don’t understand why I have to visit this big hospital every three months, because I only get to talk to my doctor for three minutes,” he said. “I had thought Korea’s health insurance system, with private doctors and national health insurance, was the world’s best, but now it’s becoming the world’s worst.”

A more robust medical work force is also essential to the country’s public health, according to the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, which has just 20 doctors out of 500 employees.

“We hope just two doctors join us a year,” said Hong Jeong-ik, director-general of the bureau of public health emergency preparedness. “They can do something meaningful for the public, even if that may not help them make huge a profit.”

Amid the national debate, wait times for care have worsened since the doctors’ walkout to protest Yoon’s proposed reforms. The president says he won’t back down on what he calls a “minimum requirement” for fixing the underlying issues. Nearly four-in-five Koreans support the expansion, polling ahead of the election shows.

“A nurse died in August 2022 at the one of Korea’s best hospitals, where she worked, because there was no doctor to treat her,” Health and Welfare Minister Cho KyooHong said in an interview. “This is not right.”

--With assistance from Kanoko Matsuyama and Sam Kim.

(Adds government comments and a warning from emergency medicine doctors to the seventh and eighth paragraphs)

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

How Bluey Became a $2 Billion Smash Hit—With an Uncertain Future

Everyone Is Rich, No One Is Happy. The Pro Golf Drama Is Back

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.