Deal of the century or ‘path to apartheid’? Inside Trump’s divisive peace plan

To rapturous applause on Tuesday, Donald Trump and his close friend Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu launched what they described as “the opportunity of a century” to fix one of the trickiest conflicts of our time.

The UK, the EU, Egypt, and most of the Gulf states made noises of commendation, saying the 181-page peace plan was a workable starting point to jump-start long-dead negotiations.

But the fractured Palestinian leadership in a rare moment of unity slammed it as “nonsense” and a “conspiracy”.

Israeli human rights groups, meanwhile, said rather than building peace it "delivered apartheid". One said it was as “detached from reality as it was eye-catching".

So, which is it?

The sprawling document, which has polarised opinion so dramatically, is almost bizarrely detailed in some respects. At one point, 100 pages in, it allocates funds for specific year-long Palestinian internships abroad.

At other intervals, however, it sweeps vaguely through some of the rawest issues at the centre of the conflict, such as what to do about the more than five million registered Palestinian refugees scattered across the globe, who have for decades kept the right to return home so close to their hearts.

Few would, however, disagree with the idea that it is the most pro-Israeli vision for a solution to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict to come out of the White House.

It states that Jerusalem will be the undivided capital of Israel, and that Israel can annex the Jordan Valley and nearly all its settlements in the occupied West Bank, although they are illegal under international law.

There will be land swaps and a cap on settlement expansion but otherwise, it appears to answer most of the key Israeli demands.

This is why Mr Netanyahu agreed to sign the document he called the “best plan for Israel and the best plan for peace”.

But it is also why it is doomed to remain just a “vision”: the Palestinians have roundly rejected it.

Instead, it serves another purpose.

The peace plan erodes previously accepted principles of peace, and the language which makes up that, so far as to do them irreparable damage. By re-framing the terms of the conflict, it sparks a paradigm shift in attitudes towards what the baselines should be.

This peace plan, unlike the economic segment which Mr Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner launched last year, does anchor its vision on a two-state solution: the widely accepted way to resolve the conflict.

But the plan acknowledges that what constitutes a “state” for the Palestinians must and will change, and so with it the notion of self-determination.

“Sovereignty is an amorphous concept that has evolved over time” begins the section outlining the future state of Palestine, which is to have little to no control over its borders, internal security, airspace or sea.

“Pragmatic and operational concerns”, chiefly Israel’s security, must come first, the plan says.

If the Palestinians agree to sign the agreement, the new state of Palestine can enjoy $50 billion worth of investment over the next decade.

Although the plan does not explain where the money will come from, the economic segment highlights an impressive array of investments into hospitals, waste facilities, roads, industries and education as well as into Israel and Palestine’s neighbours like transport links to Lebanon, power plants in Sinai and desalination projects in Jordan.

But aside from this carrot, it appears to be all stick. It is hard to see how the new state will have any sovereignty at all.

Israeli rights group B’Tselem goes as far as to compare Trump’s vision to the Bantustans of South Africa’s apartheid regime, saying Palestinians will be “relegated to small, enclosed, isolated enclaves, with no control over their lives”.

Breaking the Silence, another such group, echoed these words saying: “It is cementing occupation, fragmentation and discrimination which means apartheid”.

According to the plan, Israeli security forces will continue to be posted inside Palestine, which would have to be demilitarised.

The same security forces will have control over all international crossings into the country.

Palestine, which does have a seafront in Gaza, will be permitted no seaports for now but rather “designated terminals” in Haifa Ashdod and, if the Jordanians agree, in Aqaba.

The Israelis will have operational control over Palestine’s airspace. There will be no Palestinian airport.

The Israeli navy will have the right to block prohibited weapons and weapon-making materials from entering Palestine. In practice, this includes a number of goods, such as cables for solar panel, which are often banned under the “dual-use” argument despite having no military purpose.

Israel will have the right to launch incursions into Palestine, which will not have its own armed forces.

Expansion of Israeli settlements cannot continue but demolition of Palestinian homes can, if Israel deems the structures to pose a safety risk or if it is part of punitive measures following acts of terrorism.

The definition of key terms like refugee is questioned in the document. The right of return of any Palestinian refugee into Israel is forbidden.

Slipped into a sub-point on page 43, is that the Palestinian Authority must dismiss all pending actions against Israel in the International Criminal Court and all other tribunals.

The ICC has said recently it plans to launch an investigation into war crimes committed in the Palestinian Territories.

But it is the actual shape of the new country that speaks volumes.

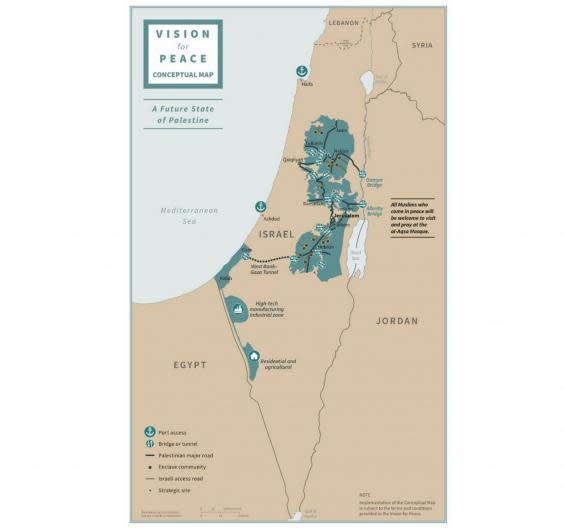

Mr Trump’s map that he tweeted out shows a perforated foetus-shaped landlocked island within Israel, with the separate territory of Gaza and a thin string of villages south of it.

Palestinian neighbourhoods within Israel will be connected to each other via “corridors” that may be converted to high-speed trains.

Its capital will not be Jerusalem - a key demand of the Palestinians who want a return to the borders before the 1967 Arab-Israel war.

Rather its capital will be based in an eastern outskirt of the city, which is currently behind Israel’s controversial wall.

And so, rights groups have roundly criticised the plan as much as the Palestinians.

Oxfam said it “undermines chances for just and lasting peace” while breaching international law.

Peace Now, an Israeli group, says the plan would not bring stability, instead giving “a green light for Israel to annex the settlements in exchange for a perforated Palestinian state.”

Certainly, one of Mr Netanyahu’s first actions following the launch was to announce he would bring a proposal to annex Israeli settlements to his next weekly cabinet meeting.

This was initially supported by US ambassador to Israel David Friedman, who on Wednesday cycled back his enthusiasm a little saying the US and Israel would form a committee to determine details first before anything goes ahead.

However, it seems inevitable annexation will happen soon.

Ambassador Friedman, who vehemently rejected the “apartheid” comparison, maintained the Trump administration has done what no other administration has done before by producing a “hard offer”.

“Not diplomatic speak but a real, documented offer to… form a Palestinian state with defined borders,” he said.

“I don’t think any other president has done more.”

Read more

There’s nothing pro-Israel about Trump’s peace plan

Iran vows to oppose Trump Middle East plan that Gulf Arabs welcome

Boris Johnson urges Palestinians to engage with Trump peace plan