How dead whales became the symbol of a political battle in NJ and elsewhere

Cindy Zipf wears a whale pendant around her neck each day to work at her office at Clean Ocean Action in Long Branch, touching the necklace and worrying that at any moment, another whale will wash onto a beach somewhere in New Jersey.

It was Zipf who first sounded the alarm on Jan. 9, two days after a second humpback whale washed ashore dead in Atlantic City, making it at the time the sixth dead whale in New York and New Jersey since Dec. 1. Zipf held a press conference in Atlantic City calling for President Joe Biden to step in and do an immediate federal investigation and halt offshore wind farm activities. Biden did not answer.

The press event thrusted whales into the crossfire of a contentious, often partisan political debate over the wind farms that reignites every time a marine mammal strands. And during this past winter and early spring, an abnormal amount of cetaceans have washed up to roil public opinion one way or the other.

Since Dec. 1, authorities have documented the deaths of 11 whales off New Jersey. At least 12 dolphins also died along New Jersey's shores.

➡ Excessive ocean noise can hurt whales. Here's how.

"All of us have been affected emotionally by this incredible situation of these whales dying," Zipf said, during an interview at her Long Branch headquarters. "We didn't anticipate this."

The debate has split environmental groups and legislatures. Zipf and U.S. Rep. Frank Pallone (D-N.J.) have together fought ocean dumping in the 1980s, and have drawn rallies against offshore drilling. But on the issue of the wind farms and whales, they have no common ground.

“Like everyone, I am deeply concerned about the recent whale deaths in New Jersey and support the ongoing investigations into marine mammal deaths and injuries. However, we should follow the science, which hasn’t linked the spike in whale deaths that started in 2016 to offshore wind planning activities that just began in recent months," Pallone said.

"I’ve been working with NOAA to address vessel strikes and entanglements, which are the major causes of preventable whale deaths. The biggest threat to the whales – and to all of us - is the increasing temperature of our oceans due to human induced emissions. The only way to save marine life, humans, and our planet from climate change is to continue to develop renewable energy like offshore wind.”

A group of environmental organizations — the Surfrider Foundation, the Association of New Jersey Environmental Commissions, the New Jersey chapter of the Sierra Club, among others — normally stand with Clean Ocean Action on environmental issues, but split from the group on the wind farm issue and whales. The groups said that warming ocean conditions related to climate change posed more of a threat to whales than wind turbines.

Whales and dolphins have long been a symbol of natural beauty and the ocean's wilderness, but in recent months, these marine mammals have taken on new meanings at the Jersey Shore. To some, they are now a warning of humanity's long reach and potentially catastrophic impacts on the natural world.

"We're so fortunate here (in New Jersey),… because we have this deep canyon known as the Hudson Canyon," Zipf said. "It's like the Grand Canyon, but it's underwater and has a whole ecosystem of its own. And then because we have the warm water of the Gulf Stream that comes up, and the Labrador Currents from the north coming down in the wintertime, we have warm water species and cold water species. We actually have one of the most diverse ecosystems for marine mammals."

But Zipf worries that diverse ecosystem is now in serious danger, and that recent whale deaths are the first of many more to come.

Experts say the construction of, and activation of New Jersey's planned wind farms could disrupt life on the ocean floor. But it simply hasn't happened yet. And, to this point, state and federal scientists say there remains no evidence connecting any recent whale death to what little activity has occurred.

It may not matter. Media of every ilk connecting recent whales to wind farms is pervasive. Tucker Carlson, prior to his ouster at Fox News, frequently made it a talking point on his television show in 2022 and 2023. Even New Jersey resident and local celebrity Snooki shot a misinformed barb at Gov. Phil Murphy, blaming him directly for the spate of mammal deaths.

Science does not point to wind. It does, however, point to a fairly common cause.

Whale appetites in busy cargo shipping lanes

Data and scientists with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Marine Mammal Stranding Center and the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection all agree the most common cause of whale deaths in New Jersey recently has been collisions with ships.

Of the whales that washed ashore in New Jersey, nearly half had wounds that experts said most likely happened from ship strikes. Most of the rest were too decomposed to determine a cause of death. A humpback whale found dead in Raritan Bay in late May, the most recent in our area, had wounds consistent with a ship strike.

Alex Costidis, an expert in whale necropsy and a member of NOAA's Marine Mammal Unusual Mortality Event working group, said many of the whale deaths appear to be the result of young animals feeding on large schools of prey fish, particularly menhaden, in busy shipping lanes and inadvertently putting themselves in danger.

"We have the same thing going on here at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay," said Costidis, who also serves as senior researcher at the Virginia Aquarium. "We seem to have some really robust menhaden fish populations. And these youngins seem to park at the mouth where the deep channel… funnels the menhaden. And they're just sitting there, gorging, right in the middle of the shipping channel… because that's a nice, deep spot."

Researchers are studying unusually high numbers of deaths among three whale species since 2016 and 2017: minke, North Atlantic right whales, and humpbacks.

A majority of the whale deaths seen in New Jersey since Dec. 1 — nine of the 11 whales reported — are humpbacks.

NOAA Fisheries spokeswoman Lauren Gaches said in an email to an Asbury Park Press reporter that the high mortality among East Coast humpback whales predates offshore wind activities and goes back to 2016. No whale deaths have been tied to offshore wind, according to NOAA staff.

When a recently dead whale washes ashore, experts look for wounds, lesions and injuries. They will also collect tissue samples to look for parasites, bacterial and viral infections, toxic algae exposure and new diseases, according to NOAA.

Whale experts are also investigating whether behavioral or ecological changes could explain the rise in deaths. Last year, a Rutgers University study found that humpback whales were spending more time in the waters off New Jersey and New York, which experts said could expose the animals to greater risks from ship strikes around the region's busy ports and other potentially harmful human activity.

At the same time, shipping traffic has broken records out of the Port of New York and New Jersey. The port was the second busiest in the nation, after the Port of Los Angeles, between January and April, according to the Port Authority.

Last year, the port moved 9.5 million TEUs, or 20-foot equivalent shipping container units.

"The seaport moved 7% more cargo in April 2023 compared to pre-pandemic April 2019," Port Authority officials said in a statement on the agency's website in May.

Whale experts say the increase in shipping traffic is putting whales are greater risk of collisions with vessels.

"You have all these large vessels that can't turn or stop very easily or very quickly," said Costidis. "They may not even be able to see these whales. The whales are busy gorging themselves, not paying attention to what's going on around them. So it's a bit of a recipe for disaster, at least with respect to the vessel strikes."

At the same time, the population of humpback whales living close to shore has increased, Costidis said.

"Humpback whales are a tricky one, because their population has been doing far better in the last decade," he said.

A whale that has never been hit by a boat may not know to avoid an oncoming ship or flee from its noise, Costidis said.

"There are whales that are far more cosmopolitan, more urban (than other species)," he said. "If you're a species that hangs out near shore, you're born into that. You're used to it, and you're used to the noise. You're used to the disruption."

From whaling to ecotourism

On a blustery and chilly final day of March, the 120-foot long, whale watching vessel Atlantis made its way east down the 3 ½ mile long Cape May canal to the inlet and then slipped out into the Atlantic Ocean. She was carrying 25 bundled-up passengers, several with cameras or binoculars strapped around their necks with hopes to spot a whale.

Capt. Jeff Stewart Jr. said they’d seen one the previous weekend, but the wind posed a challenge to any whale sightings on this day. It was blowing in hard from the southwest and had kicked up a swell. As the boat broke the inlet and the bow dipped into the waves though, he spotted a pod of bottlenose dolphins arcing through the water.

While he stood on the top deck with a microphone close to his mouth, narrating the nature scene playing out before him, his father Jeff Stewart Sr. maneuvered the boat to stay with the dolphins. At one point he brought the boat into 12 feet of water as the dolphins swam with the tide down Poverty Beach.

“What I like about this job is you get to meet people every day and see their reactions. Sometimes you get 125 people on board, and you hardly know they’re there. But then you get a group that’s shouting ‘Wow, that’s amazing,’ the whole time. Or you get people who’ve never seen the ocean or a dolphin outside of an aquarium and their jaws drop open. That’s the way it should be,” Jeff Stewart Jr. said.

Whale watching is a growing ecotourism business in Cape May, and elsewhere on the New Jersey coast. The Stewarts, which have been running tours since 1992, have two vessels in their Cape May Whale Watching fleet. Jeff Stewart Jr. said they carry about 60,000 people throughout their season, which runs from March through December.

Their customers come mostly from New Jersey and Pennsylvania, but being that Cape May is major tourist destination, people that hop on the tours come from all over the country and abroad.

“Whales are such beautiful, graceful, and huge creatures. We went up to Alaska once to see them and we saw a mother and a calf together. We saw the water spout out from their blowholes,” said Marie Valentine Boutte, who was visiting Cape May with her husband, Ed, a retired National Parks Service ranger, on their 16th wedding anniversary.

While whale watching contributes to Cape May’s economy today, whaling once played a major role in the settlement of the cape in the late 1600s and 1700s.

The Museum of Cape May County has the journal of Lewis Cresse detailing the life of a whaler in the mid-18th century. Cresse who lived from 1720 to 1769, was a Cape May farmer who went on monthlong whaling voyages in the early part of almost every year. He was one of many whalers hoping for a big pay day. One whale could fill 23 barrels of oil.

It could be a risky venture at times. On one fateful trip in 1764 a whale struck their boat with such swiftness that it was thought she broke the boat into 500 pieces.

Town Bank was an original whaling village founded in the 1670s by whalers. When the Atlantis makes its way around the cape and into Delaware Bay, Jeff Stewart Jr. points out the location to the passengers on board. The original village had long ago eroded into the bay, but there are still some bluffs.

Over the microphone Stewart explained that the villagers would watch for the whales from the bluffs. Then the men would row out in longboats and try and harpoon one.

“If they got one, the whale would tow them around the bay for a while. Then everyone from the village would pull the ropes from the beach to bring the whale in to butcher,” Stewart said.

Whaling took its toll on the population in the bay, forcing whalers to travel much farther to capture one. Gradually the settlers in Cape May turned to less-arduous work of cattle raising, farming and trapping. Whaling, however, was undertaken well into the late 1700s. The last whaling transaction recorded occurred in 1775.

The whales are back, at least the humpbacks are, and Stewart said they have a 68% rate of seeing a whale on their trips. The odds are much higher for dolphins, which he said they see 98% of the time.

But here too there is apprehension, not about busy shipping lanes, but wind farms.

“I am concerned about the industrialization of the ocean. It’s a large-scale project and I don’t think everybody knows just how large a project we’re looking at,” he said.

New Jersey officials have approved three offshore wind projects so far east of Cape May, Atlantic City and Long Beach Island. The projects — two by Denmark-based Ørsted and another by Atlantic Shores, a partnership between oil company Shell and EDF Renewables North America, based in San Diego — would generate enough energy to power 1.7 million New Jersey homes, according to the companies.

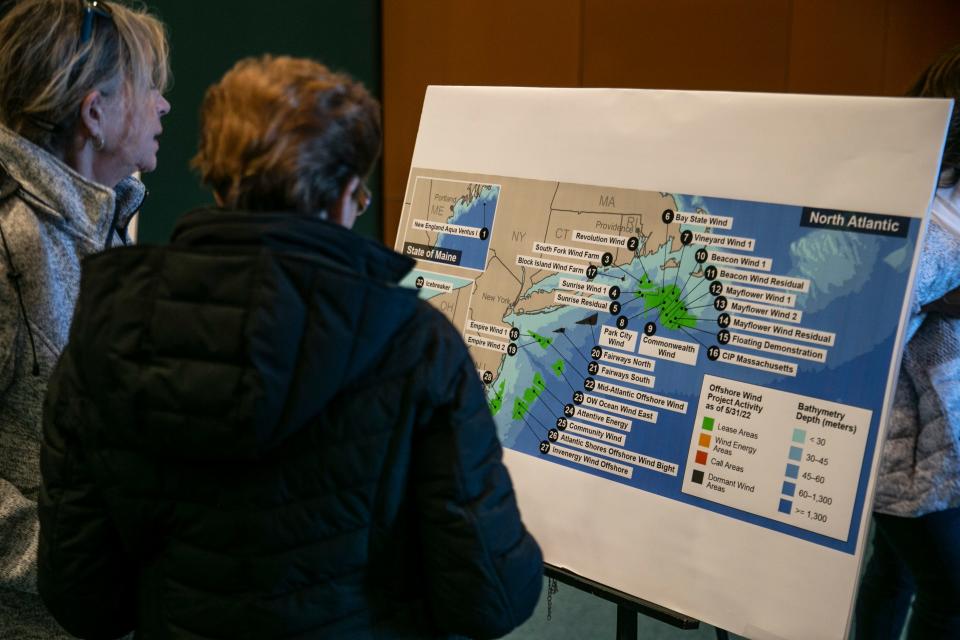

Additional offshore wind projects to the north and east are under development as well. Across the New York Bight and Jersey Shore region, more than 911,000 acres of ocean — or more than 1,400 square miles, an area larger than Rhode Island — have been leased through the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management for wind farm development.

Zipf, of Clean Ocean Action, worries the extent of these projects could irreparably harm whales and other ocean life.

Clean Ocean Action has been pressing elected officials for pilot studies on offshore wind environmental impacts before expanding the farms along broad swaths of the Atlantic Coast. Zipf has numerous concerns about the technology: more ships at sea during construction, increases in manmade noise from sonar seabed mapping and pile driving turbine supports, and other possible unintended consequences from placing hundreds, possibly thousands, of large turbines into the ocean.

"We're on the verge of massive industrialization without really understanding the consequences, or what's at stake," she said.

Global warming, whales and the unknown

Much of the debate about the recent whale deaths centers on a concern that underwater seabed mapping by offshore wind companies has spooked or physically harmed whales.

"There's no evidence of a connection between the whale strandings or marine life that has washed up, devastatingly, on our shore and activities related to offshore wind," said Ed Potosnak, executive director of the New Jersey League of Conservation Voters.

A number of New Jersey-based environmental groups have echoed the support for offshore wind, saying that ocean warming and changes in prey distribution pose greater threats to whales than offshore wind farms.

Officials with both of New Jersey's offshore wind companies said they have no incidents of whale accidents and their mapping operations do not harm the cetaceans.

"The completed surveys did not involve sounds or actions that would harm whales or other marine mammals and Ørsted-contracted vessels have not experienced any whale strikes during offshore survey activity in the U.S.," Ørsted's head of government affairs Maddy Urbish said in a statement. "It’s important for all ocean users to continue working with state and federal officials to further advance science-based, smart policies that protect critical marine life while addressing climate change."

Atlantic Shores Offshore Wind officials said they work with Rutgers and Stockton universities to assess their impact on marine life, and have third-party, marine animal observers on board their vessels to watch and listen for any species who might be harmed by construction work.

Potosnak said a misinformation campaign funded through fossil fuel companies, particularly the conservative leaning-Caesar Rodney Institute of Delaware, are behind the blame on offshore wind for the whale deaths.

"The fossil fuel industry is dumping boatloads of money into their efforts to spread this misinformation," he said. "It's deeply concerning. And with it, I think the politics have also started to take root… Folks are responsive to what they're hearing in their community, and unfortunately, we're hearing a lot of misinformation that's being spread."

Whales face more risks from climate change than offshore wind noise, Potosnak said. Experts say climate change will likely change prey species distribution areas and whale habitat as water temperatures change.

In the 2020 New Jersey Scientific Report on Climate Change, scientists said climate change would affect humpback whale breeding and feeding sites, and could disrupt their migration timeline as well as the arrival of their prime food sources, like menhaden.

But offshore wind opponents point to offshore wind survey work and preconstruction activity and allege they are immediate threats to local whales. Republican lawmakers have attended whale rallies across New Jersey, each event attracting hundreds of concerned residents. Those lawmakers have called for a moratorium on offshore wind work and thorough studies into the whale deaths.

"Whales are the canaries in the coal mine," Rep. Chris Smith of New Jersey said in April during a meeting of county, state and federal elected officials at Seven Presidents Oceanfront Park in Long Branch to call for an offshore wind moratorium.

Smith told the Press that environmental studies on offshore wind development were insufficient and that scientists are engaged in a "group think" in dismissing offshore wind's impacts on whales and other marine mammals.

The congressman said he is working with other federal officials to task the Government Accountability Office with conducting an independent study of offshore wind and whales.

"The environment isn't just above ground, it's below sea," said Smith. "The sea bed is going to be devastated by this, and everything that grows and thrives there."

Democrats, too, now are calling for answers. A group of Democratic U.S. Senators — including Cory Booker and Bob Menendez, both of New Jersey — called on NOAA and sought to steer additional resources to the agency in order to investigate the whale deaths and better protect the animals.

"We believe accessibility, transparency, and timeliness is of the utmost importance for NOAA’s whale injury and death reporting," the senators wrote in a letter to the agency's National Marine Fisheries Service.

"Not every whale death is caused by humans," said Samantha Muka, a historian of marine science at Stevens Institute of Technology. "A lot of people don’t understand that cetaceans can die without human interaction. They live a normal life cycle, and they die. Mortality at all ages is a normal process.”

NOAA has kept records on unusual mortality events since 1991. Roughly half of marine mammal death cases since 1991 have been closed with an "undetermined cause of mortality."

Regarding this recent spate of whale deaths since December, Muka said, “The likelihood that we will know what killed the whales, other than the ship strikes or entanglement, is pretty low."

The "unknowing" continues to fuel the ongoing political debate.

"It’s an argument about the unknowing. And people love those types of arguments in politics, because if you don’t know you can say it's anything. And unfortunately, the ocean is very unknowing," she said.

Can we save the whales?

While New Jersey's prominent Republican officials have called for a moratorium on all offshore wind activity to protect whales, federal officials are considering a different approach, one that targets speeding ships outside of busy Atlantic ports.

A 10-knot speed limit that currently applies to ships over 65 feet long would be expanded in whale Seasonal Management Areas to ships over 35 feet long, under a proposal by NOAA. Already, the smaller ships are voluntarily asked to comply with the speed limits to protect whales, particularly endangered North Atlantic right whales.

The zones would also be expanded and extend along much of the length of the Atlantic Coast and as far out as 100 miles offshore in some places.

NOAA's rule is designed to help protect the very last of the North Atlantic right whales, whose population is down to an estimated 350 individuals. Of those, only about 70 are breeding females, according to NOAA.

Marine industry stakeholders, however, are not all on board with the 10-knot rule. John DePersenaire, director of government affairs and sustainability at Viking Yachts, said it’s a broad-brush tool and not a long-term solution. One of the main issues Viking Yachts has with it is boater’s safety, particularly the center consuls in the 35- to 65-foot range that are powered by double or triple outboard engines.

“We put a tremendous amount of time on hull design. These boats are designed to be more efficient and safer when they’re on a plane,” DePersenaire said.

Planing is when a boat is supported by hydrodynamic lift instead of buoyancy, which requires the boats to travel at speeds over 10 knots in order to lift.

Another issue is that the charter boats work on schedules and the 10-knot speed will limit where they can fish on any given day.

“We are committed to mitigating our risk of hitting a right whale. A whale strike can be catastrophic to us and the whale. But the chances of our boats hitting a whale are extraordinarily small,” DePersenaire said.

The marine trades have formed a group called Whale and Vessel Safety, or WAVS, to develop methods to bridge the gap between monitoring equipment, boat operators, and marine mammals by providing near real-time warnings inareas where right whales are seen or predicted to be. This would be in place of the 10 knot speed restriction.

On June 8, the U.S. Department of Congress decided to give NOAA $82 million from the Inflation Reduction Act to use near real-time monitoring to track whales and reduce the risk of vessel strikes and entanglements. The money would also fund the development and evaluation of new technologies, such as satellite observations to transform North Atlantic right whale monitoring and to improve understanding of the whales’ distribution and habitat use.

However, it is not in lieu of the proposed 10 knot restrictions, which is remains on the table.

Zipf and Clean Ocean Action want to see an extensive pilot study of the offshore wind farms' impacts before large areas of the Atlantic are developed, as an assurance that the whale populations will not be harmed by the farms' construction or operation.

"We want to see a pilot project so we can understand more about what the consequences are," she said during a meeting with the Asbury Park Press in her Long Branch office. "The science is really behind the permitting (timeline), and that's not a good state of affairs."

This article originally appeared on Asbury Park Press: Whales dying along NJ coast: a symbol for a political war