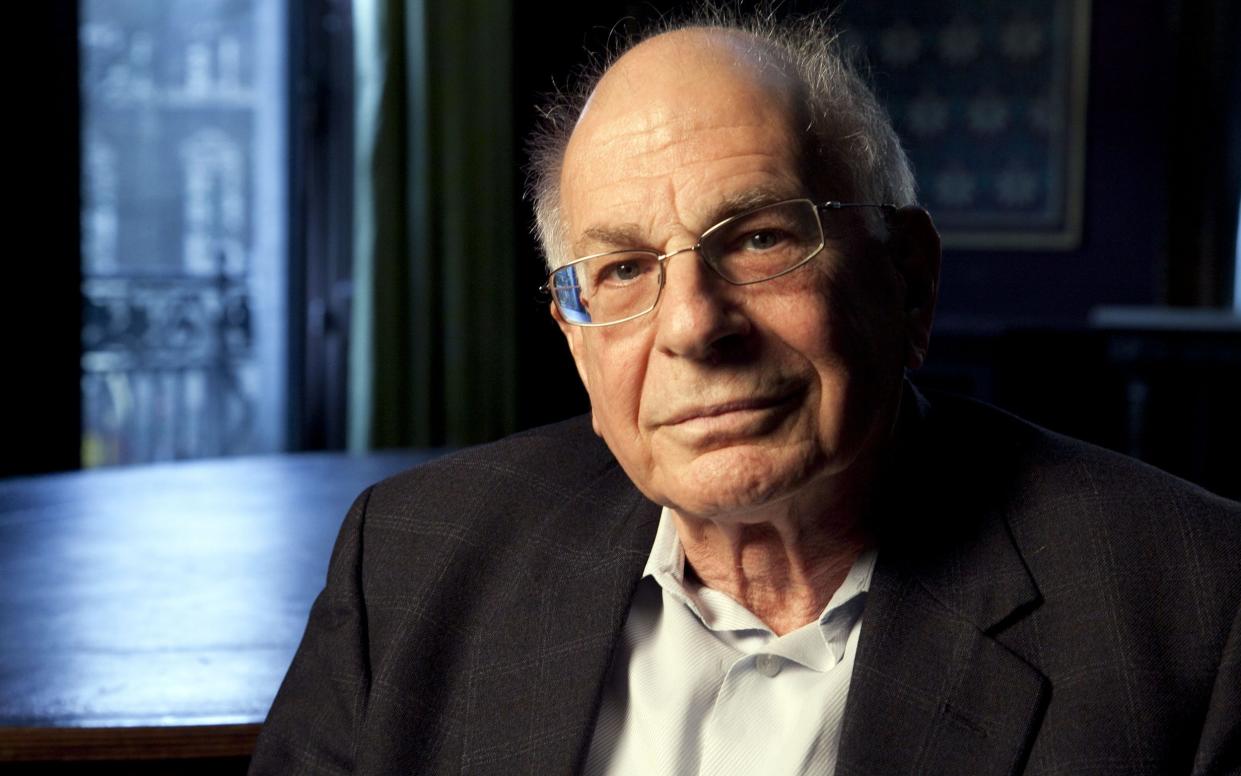

Daniel Kahneman, Nobel Prize-winning psychologist who changed the way we think about economics – obituary

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Daniel Kahneman, who has died aged 90, was a psychologist who shared the 2002 Nobel Prize in economics, with Vernon Smith, for work carried out with Amos Tversky which revealed the inadequacy of the most basic assumptions made by economists – that man is a rational being – and led to the creation of a new strand of economic thinking, behavioural economics; he also had interesting things to say about Brexit.

To the non-specialist Kahneman was best known for his 2011 bestseller Thinking, Fast and Slow, a distillation of a lifetime’s research in which he explained that the human brain has two interrelated systems that create “systematic errors in thinking”.

System 1 (fast thinking) is the mental state in which people drive a car or do the shopping. Largely intuitive, prone to make snap judgments, it is also highly susceptible to being misled.

System 2 (slow thinking) understands that system 1 might be unreliable and often intervenes to avert a mistake. But because it requires more effort, system 2 is also inherently lazy and is inclined to act as an apologist for system 1, providing rationalisations for emotional responses. The less intelligent people are, the less they tend to deploy the critical arts of system 2 and the more militantly confident in their own judgment they tend to be.

Kahneman recounted how he and Tversky (who died in 1996) demonstrated that human beings have an inbuilt and predictable set of cognitive biases that lead to logically flawed decisions.

In one experiment they rigged a wheel of fortune so that it would land on only two numbers: 10 or 65. “One of us would stand in front of a small group, spin the wheel, and ask them to write down the number on which the wheel stopped... We then asked them two questions: Is the percentage of African nations among UN members larger or smaller than the number you just wrote? What is your best guess of the percentage of African nations in the UN? The average estimates of those who saw 10 and 65 were 25 per cent and 45 per cent, respectively.”

Astonishingly, people were clearly and unwittingly influenced by having seen a random number, as it affected their attempt to answer a completely unrelated question – a phenomenon known as “anchoring”. Kahneman and Tversky were not the first to observe the phenomenon, but were the first to demonstrate its effect on human judgment.

In another case a group of German judges were asked, before mock-sentencing a shoplifter, to roll a pair of dice rigged to come up either three or nine. Those who rolled nine gave the offender eight months on average, while those who rolled three gave five months.

Another example of cognitive bias cited by Kahneman was the way people routinely gamble to avoid guaranteed losses, while playing safe with guaranteed gains, leading them to react differently to a choice that is fundamentally the same. In one experiment, doctors were asked to choose between two treatments for lung cancer: surgery or radiation. When told that the one-month survival rate after surgery was 90 per cent, as many as 84 per cent of the doctors chose the surgical option. When the doctors were told there was 10 per cent mortality in the first month post-surgery, only half chose surgery.

Such experiments had far-reaching implications for economics, showing that, contrary to the assumptions of efficient-markets theory, people do not strive to maximise “utility’ and minimise risk.

One of the most damaging inbuilt biases, in Kahneman’s view, is the natural human urge to create false narratives to account for past events, making it difficult to learn from our mistakes. “When you read The Big Short [by Michael Lewis] you think that those who didn’t see the [2008] crash coming must have been either blind or knaves,” he told The Daily Telegraph in 2016. “But... a great number of highly intelligent people didn’t see it coming. The crash was not as predictable as it now appears. We have learnt the wrong lesson... We deny the uncertainty we face and learn that crises are predictable, when we should learn the opposite.”

That interview was published two weeks before the referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU and Kahneman warned that the debate was being driven by psychological processes that could lead to a terrible misjudgment.

“The major impression one gets observing the debate is that the reasons for exit are clearly emotional,” he observed. “The arguments look odd: they look short-term and based on irritation and anger.” The risk, he went on, was that the British people would be swept along by emotion and lash out later at scapegoats if the withdrawal proved to be a disastrous strategic error. “They won’t regret it because regret is rare. They’ll find a way to explain what happened and blame somebody. That is the general pattern when things go wrong and people are afraid.”

Daniel Kahneman was the son of Lithuanian Jews who had emigrated to France in the 1920s, although he was born in Tel Aviv, in British Mandate Palestine, while his mother was visiting family there on March 5 1934.

His father was head of research for the L’Oréal factory in Paris when Germany invaded France in 1940 and young Daniel’s experience of the war fomented an interest in human behaviour.

His father was picked up in the first large-scale sweep for Jews and interned for six weeks in Drancy, a stepping stone to the death camps. Then, mysteriously, he was released, thanks in part to the owner of L’Oréal, a leading donor to the fascists. The family escaped to Vichy France until the Germans arrived then fled again, to Limoges in central France, where they lived under false identities in a chicken coop.

One evening Daniel violated the curfew for Jews and found himself face-to-face with a German soldier in SS uniform, who, he saw to his horror, was staring at him intently: “Then he beckoned to me, picked me up, and hugged me,” Kahneman recalled in a memoir. “He was speaking to me with great emotion, in German. When he put me down, he opened his wallet, showed me a picture of a boy, and gave me some money.”

He also recalled a young Frenchman, a Nazi collaborator and passionate anti-Semite, being so fooled by his sister’s disguise as to fall in love with her: “After the liberation, she took enormous pleasure in finding him and letting him know he had fallen in love with a Jew.”

Kahneman’s father died as a result of untreated diabetes in 1944, and after the war his mother moved the family to Palestine, soon to become Israel, where Kahneman obtained a degree in psychology and mathematics from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem before being drafted into the Israel defence forces as a platoon leader. Transferred to the psychology branch, he found himself frustrated by the system for assessing candidates for officer training, which relied heavily on intuition.

He went on to design a structured-interview system, which required interviewers to measure young men on six dimensions in a specific order, and only then use their intuition to imagine what kind of soldiers they would make. The system is still in place today.

After two years of military service Kahneman studied for a PhD at the University of California, Berkeley. In 1961 he returned to the Hebrew University to take up a lectureship, and in 1970 a professorship, in psychology. In 1978 he took up a job at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

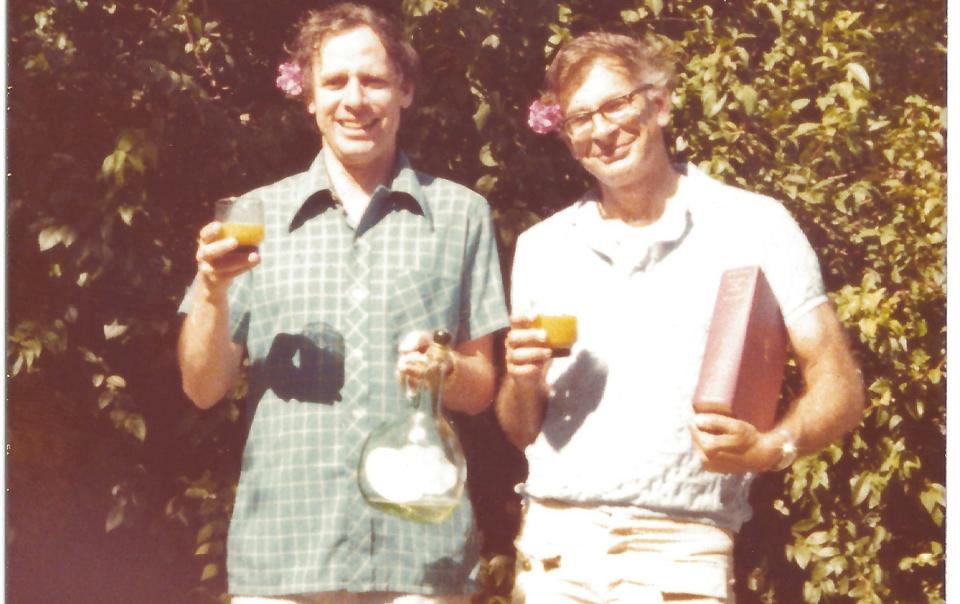

The research that first caught the public eye was his study of pupil dilation. Using primitive equipment, he and a colleague discovered that when people were exposed to a series of digits they had to remember, their pupils dilated steadily as they listened to the digits, and contracted when they recited the series. But it was his collaboration with Tversky, whom he first met in 1969 in a Jerusalem cafe, that would prove the most productive.

In their first paper, The Law of Small Numbers, they showed how people were inclined to trust information garnered from ridiculously small samples and see patterns in events and numbers that are, in fact, random.

But it was for their seminal articles in the general field of judgment and decision-making, culminating in the publication of their Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk in 1979, that earned Kahneman his Nobel Prize.

Prospect theory argues that people’s degree of pleasure depends more on their own subjective experience than on objective reality. A shopper, for example, might drive across town to buy a £10 calculator instead of a £15 one but forgo the same trip to purchase a £125 jacket for £5 less, illogically believing the greater percentage saved on the calculator makes the trip more worthwhile.

Behavioural models derived from such studies forced economists to recognise that they could no longer base their analyses on the fundamental assumption of rational behaviour.

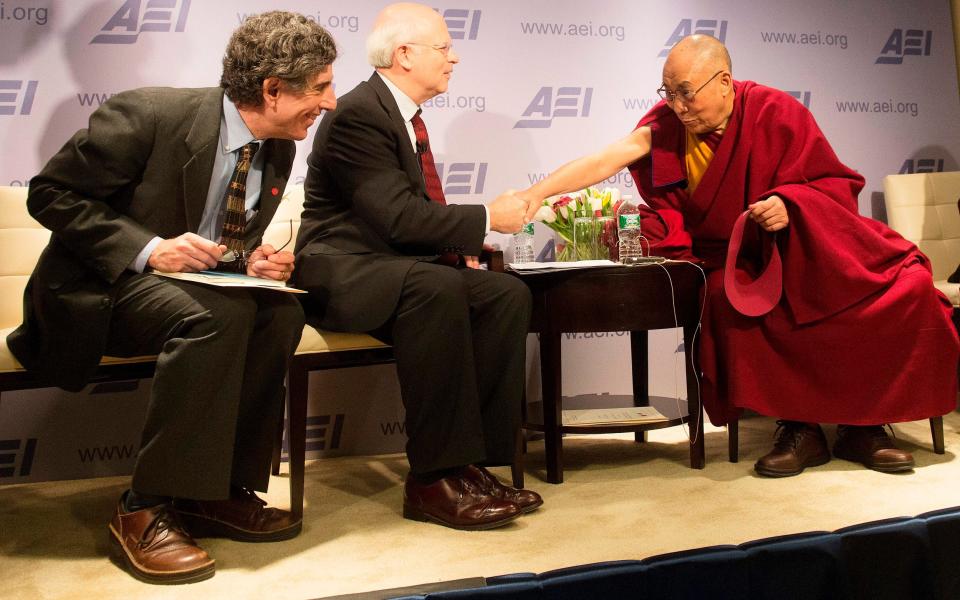

In 1993 Kahneman was appointed to a chair in psychology at Princeton, and the focus of his research gradually shifted towards “hedonic psychology” – the study of the discrepancy between how people experience events while they are actually happening, and how they remember those same experiences. His work led him to conclude that people mainly derive satisfaction from the perspective of the stories they tell about their lives.

Kahneman won numerous awards in addition to the Nobel Prize and in 2015 The Economist listed him as the seventh most influential economist in the world.

Kahneman married, first, Ira Kahn, an Israeli social researcher. They divorced, and in 1978 he married Anne Triesman, a Yorkshire-born cognitive psychologist and fellow of the Royal Society, who died in 2018. He is survived by his partner Barbara Tversky, the widow of Amos Tversky, by a daughter and son from his first marriage and by four stepchildren from his second.

Daniel Kahneman, born March 5 1934, died March 27 2024