Cyborg Guinea Pig's Inner Ear Becomes a Battery

A science fiction nightmare of human bodies becoming batteries in "The Matrix" is still far from reality. But a new experiment that transformed the inner ear of guinea pigs into a biological battery raises more hopeful possibilities for such technology.

Electrodes implanted inside the guinea pigs' inner ears, which bear a strong resemblance to that of humans, succeeded in powering up attached radio transmitters — all without the furry mammals suffering from major hearing loss. That marks the first time researchers have harnessed electrochemical power in mammals, and could pave the way for medical sensors implanted in human inner ears.

"It will allow us to develop fully implanted electronics (e.g., inner ear sensors that have a wireless chip) without the need for a traditional battery," said Anantha Chandrakasan, an electrical engineer and computer scientist at MIT, in an email. "The system will be self-sustaining."

Implanted electronics could track the health of the inner ear and parts of the human body located just millimeters from the inner ear — the carotid artery, the facial nerve, and the brain's temporal lobe. Future sensors could also monitor deafness among young kids with hearing aids, or track the hearing sensitivity of U.S. soldiers or civilian workers at risk of hearing loss, said Konstantina Stankovic, an otologic surgeon at Harvard University who worked with Chandrakasan.

Animals such as cockroaches, snails and clams have previously become living batteries in labs. But the possibility of harnessing electrochemical power in mammals brings the idea much closer to humans. [Quiz: Sci-Fi vs. Real Technology]

The battery power of the inner ear comes from the difference in electrical charge between the inner ear's endolymph and perilymph fluids. That steady power source could prove much more reliable than other methods of harvesting power from body heat, motion or vibration, according to the Harvard-MIT team that detailed their work in the Nov. 11 issue of the journal Nature Biotechnology.

"The inner ear in particular is particularly attractive because it's a stable source of energy and it's maintained throughout life," Stankovic told TechNewsDaily.

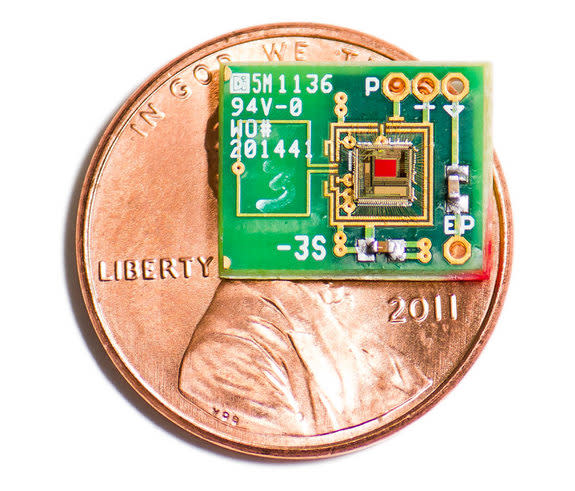

But researchers had to use a single burst of radio waves to "kick-start" the control circuit because the inner ear's voltage — the electrical charge difference — was too low. They also had to design their electronic device to run on the mere nanowatts (billionths of watts) of power available from the inner ear by building up charge until enough power became available.

"So we can accumulate energy on an energy storage device and then burst energy to power higher power electronics," Chandrakasan explained. "When the transmitter and sensor is off, we have to manage the power by shutting them off completely."

The MIT-Harvard team still hopes to figure out how to make electrodes of the right size to minimize damage to the inner ear while still extracting enough power. The researchers also want to take the next step of implanting both the electrodes and the electronic device inside the guinea pigs' ears, rather than just the electrodes.

"We hope to make a completely implantable device altogether with the miniaturization of sensors," Stankovic said. "Ultimately, we would like to see it applied in humans."

This story was provided by TechNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow TechNewsDaily Senior Writer Jeremy Hsu on Twitter @jeremyhsu. Follow TechNewsDaily on Twitter @TechNewsDaily, or on Facebook.

Copyright 2012 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.