To cut pollution, old-school sailing boats are taking on diesel megaships

Amid the dozens of cargo ships now steering through the North Sea, one vessel stands apart: the Avontuur, a 144-foot-long schooner powered only by the wind and sun.

Stocked with crates of artisanal gin and vodka, the emissions-free cargo ship is making its maiden voyage from the tiny town of Elsfleth in northwest Germany and around the tip of Denmark to Rostock, on Germany’s northeast coast.

SEE ALSO: All of Germany's new cars could be emissions free by 2030, report says

After Rostock, the crew plans to spend the next one to two years hauling organic wines, fair trade coffee and other sustainable fare to ports across Europe, North America, the Caribbean and, eventually, Australia.

The Avontuur, whose name means “adventure” in Dutch, is the newest and biggest member of a growing fleet of cargo ships that combine centuries-old technology — sails and masts — with modern inventions like solar panels and battery generators.

The goals of the emissions-free shipping movement are two-fold, said Cornelius Bockermann, the Avontuur’s captain and founder of Timbercoast, the company behind the mission.

The first is to capitalize on the rising consumer demand for products with little to no carbon footprint.

After all, how good for the planet are organic blueberries from Chile if shipping them to New York means burning diesel bunker fuel or aviation fuel?

“More people want this to be shipped to their doorsteps in a sustainable way, and not the traditional way,” Bockermann told Mashable.

“The only way to combine this organic produce and the consumer demand is with a cleaner way of transport.”

The second — and more important — goal is to draw the world’s attention to the broader environmental challenges facing the shipping sector, which hauls roughly 90 percent of globally traded goods.

“We carry a lot more than cargo. We carry a message,” Bockermann said. “We want to make people think about the consequences of their consumption.”

The shipping exception

As countries and companies work to reduce planet-warming emissions from power plants and automobiles, they’ve made far less progress on limiting emissions from two particular modes of transportation: marine shipping and aviation.

Both of these sectors have been exempted from the U.N. climate treaty process, including the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement.

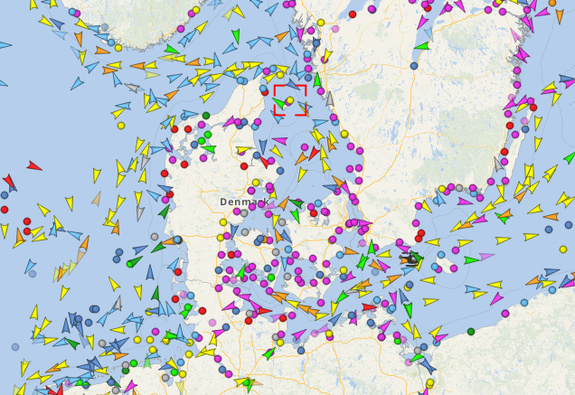

Image: Vesselfinder.com

As with the aviation industry, a big reason why emissions from cargo ships are so difficult to regulate is that, unlike a stationary coal plant, the ships travel from country to country, making it harder for a single government to monitor and regulate them.

Yet if policymakers and the shipping industry don’t shake things up, carbon emissions from shipping could rise anywhere from 50 percent to 250 percent by mid-century compared to today’s levels, depending on economic growth, according to the International Maritime Organization (IMO).

With emissions expected to decline in other sectors, that means shipping will make up a bigger slice of the carbon pie, rising from about 2.5 percent of total global carbon dioxide emissions in 2012 to 17 percent by 2050, according to the IMO.

“Shipping is still out-of-sight, out-of-mind. People don’t see ships like they do trucks,” said Charlene Caprio, an attorney and expert on maritime, energy and environmental law in New York City.

Image: Getty Images

The lack of effective oversight could make it harder to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement — specifically the temperature target of limiting warming to less than 2 degrees Celsius, or 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit, above preindustrial levels through 2100.

A quest for cleaner shipping

The upward sloping curve of shipping emissions makes the carbon-free shipping movement seem downright contrarian. The ships they're sailing may look like mere specks next to the behemoths that carry most of the world's cargo, but the movement they represent is likely to make some waves.

Caprio is a member of Sail Med, a team of energy experts and devoted sailors who advocate for wind-powered cargo shipping. Based in Greece, Sail Med is currently outfitting a 43-foot square rigger to handle a small load of cargo — about 10 tons — for local shipping in the Aegean Sea and beyond.

The Avontuur can haul nearly eight times that amount, with a capacity for 77 tons of cargo.

The 96-year-old schooner embarked on its first mission on July 28 and is expected to arrive in Rostock by Aug. 11 for the start of Hanse Sail, a festival featuring other old-school vessels, though none of the others are equipped to carry cargo.

Bockermann said he spent more than 700,000 euros ($786,000) from his personal savings to upgrade the Avontuur into a working cargo ship. A team of more than 100 volunteers from around the world helped carry out the renovations and take it for test runs.

Avontuur Shipping Co., as the project is formally called, is now seeking to raise around 630,000 euros ($708,000) from individual investors, who can purchase small shares in the company and would split the profits from the Avontuur’s import-export business.

“We want this to rest on as many shoulders as possible,” Ben Decosse, a spokesperson for Timbercoast, said by phone from Germany.

The small-investment model is similar to the approach used by Fairtransport, one of the clean shipping movement’s pioneers.

Based in the Netherlands, the company has operated a 105-feet-long schooner, named the Tres Hombres, since 2009. The refurbished ship can haul up to about 39 tons of rum, wine, cacao beans and other goods, and, with its set of 12 sails, looks more like a ship captained by pirates than a modern cargo vessel.

Tres Hombres is now making its way back to Europe after its seventh TransAtlantic voyage to the Americas and Caribbean.

Fairtransport is also part of an ambitious European Union-backed initiative to build a large hybrid ship that runs on both engine power and “wind-assisted ship propulsion” — offering shippers a middle option between Christopher Columbus-style schooners and diesel-guzzling mega-ships.

Image: Dykstra Naval Architects

One of the proposed ships to come out of the EU initiative is the Ecoliner.

Designed by Dykstra Naval Architects, it will use historic weather data and computer simulations to find routes with the best trade winds, allowing its sails to do most of the legwork and limiting the ship’s overall appetite for fuel.

The project’s founders are now searching for investors to permit them to actually build the boat.

Greening the regular fleet

At the same time as the Avontuur and other relatively small wind-powered vessels are cruising the seas carrying specialty goods, conventional cargo ships are also becoming somewhat cleaner.

This is due to advances in aerodynamic designs, energy-efficient engines and other modern upgrades that limit the use of fuel.

Making their vessels more fuel-efficient is a priority for many shippers, since it is such a large part of a voyage's costs.

Maersk Group, the Danish shipping giant, is building a new line of mammoth cargo ships that it claims will reduce carbon emissions by 35 percent per container shipped, compared to the industry average on routes from Asia to Europe.

These "Triple-E" ships stretch more than 1,300 feet long and can carry more than 18,000 20-foot containers per trip, about 16 percent more than Maersk's previous largest ship, and orders of magnitude greater than the comparitively tiny Avontuur.

Despite the ship’s size, Maersk claims that the Triple-E is actually the most energy-efficient way to move cargo, due to its energy-saving designs and because the behemoth vessel can replace several smaller cargo ships on a particular route.

Shipping's carbon challenge

Yet all of these advancements won’t be enough to keep the global shipping sector’s emissions from rising in coming decades, experts said.

As the world’s population booms and the middle class expands in developing economies, more boats will make more trips to bring food and goods to billions of consumers.

“You’ll see an industry that goes from currently being only responsible for 2.5 percent of carbon emissions to growing into the double digits,” Ian Petty, general manager of the Sustainable Shipping Initiative (SSI), told Mashable.

“And that’s going to be happening at a time when other industries are making significant reductions in their carbon emissions,” he added.

SSI is a coalition of global shipping companies and major exporters.

Image: Getty Images

Petty said SSI is pushing the IMO and industry groups to enact concrete measures for cutting emissions and fuel use.

The IMO’s next chance to act will be at its 70th Marine Environment Protection Committee meeting, slated for late October in London.

“That needs to happen sooner rather than later,” Petty said about the measures. “We’re just putting off the inevitable by delaying.”

Bockermann, the Avontuur’s captain, said he recognizes that carbon-free shipping will make only a minuscule dent in the industry’s use of fossil fuels.

He also acknowledged that while a niche group of people will pay a premium for sustainably shipped spirits or coffee, many consumers will continue to buy cheap commodities moved by hulking, petroleum-powered vessels.

Instead, the captain said he hopes that the Avontuur and projects like it will raise pressure on the shipping industry to curb emissions and compel consumers to contemplate their own carbon footprints.

“We won’t change the world, we won’t change the shipping industry,” Bockermann said.

“But we want to set an example and we want to use this ship as an ambassador and show what's going on.”