On criminal justice reform, policy prevails over politics

WASHINGTON — On Thursday afternoon, an all-star team from across the conservative movement gathered on Capitol Hill to celebrate a major accomplishment of the Trump administration. Standing with Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah, in a wood-paneled Senate meeting room, were members of Americans for Prosperity and Freedom Partners, two groups funded by the libertarian billionaires Charles and David Koch. Paula White, a spiritual adviser to President Trump, was there. So was Bernard Kerik, the former commissioner of the New York City Police Department, and Ken Cuccinelli, the former Virginia attorney general closely associated with the tea party movement.

They were not cheering for the funding of a border wall with Mexico or new trade tariffs. Instead, these conservative luminaries had come to Capitol Hill to help push across the legislative finish line a goal much more closely associated with the leftward terminus of the political spectrum: criminal justice reform.

Any day now, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., will bring the First Step Act to the Senate floor. It is expected to pass that chamber with as many as 70 votes and be signed by Trump shortly thereafter (a version of the bill passed the House last May). When he does so, Trump will have reversed more than two decades of tough-on-crime policies, most notably President Bill Clinton’s 1994 crime bill and President Ronald Reagan’s 1986 drug bill.

“We need a just criminal justice system,” Maya Wiley, a senior vice president for social justice at the New School, told Yahoo News. “The sentencing act is a start.”

Wiley, who rarely finds herself endorsing proposals from the Kochs, and her conservative counterparts may have different reasons for supporting the First Step Act. Many of those who spoke on Thursday afternoon on Capitol Hill framed criminal justice reform in terms of religious redemption, individual liberty and reducing government waste.

Lee described an experience from his time as a federal prosecutor in Utah, when guidelines effectively forced a federal judge to sentence a small-time drug dealer, a father of two, to a 55-year sentence, since at the time of his arrest, the dealer was in possession of a firearm. The judge then wrote an opinion criticizing the harshness of his own sentence. A line in that self-dissent that would “haunt” Lee for years to come, as he made his way from the judicial to the legislative branch of government.

“Only Congress can fix this problem,” the judge wrote.

Kerik, the former NYPD commissioner, once also ran New York’s notoriously grim jail system. But in 2010, he went to federal prison on tax-related charges. Kerik served three years at a prison in Maryland, where he found himself surrounded by young black men from Baltimore and Washington, D.C., serving lengthy sentences for seemingly minor offenses. The onetime supporter of the death penalty saw that the priorities of the federal corrections system had become deeply skewed. He described meager educational and self-improvement offerings that included crocheting and playing checkers. “We over-punish,” Kerik said, “and we have no incentives for good behavior.”

The First Step Act intends to address the concerns of Lee and Kerik by reforming both the length of prison sentences and conditions under which those sentences are served. Some of the bill’s proposals are intended as specific fixes: It will no longer be permissible to place juvenile prisoners in solitary confinement; female prisoners will have access to free tampons; inmates will have greater access to opioid addiction treatment programs. Prisoners will also be incarcerated no more than 500 miles from their homes. The bill will also make it easier for them to contact family members. Though seemingly small, these reflect humane reforms that activists had long advocated for (as with all aspects of the law, these measures apply only to prisoners in the federal corrections systems; the vast majority of prisoners are housed by state and local institutions.)

But there are also dramatic changes, in particular regarding the severity and length of sentences. If passed, the First Step Act will allow judges to hand down sentences below mandatory minimum guidelines, though only in the cases of nonviolent drug offenders with little criminal history. It reduces the penalty for a “third strike” conviction from a life sentence to 25 years. Perhaps most importantly, it retroactively applies the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, which corrected the disproportionately strict sentences given for possession of crack cocaine relative to the same drug in powdered form. Kara Gotsch of the Sentencing Project estimates that some 2,700 inmates will have their sentences reduced because of the retroactivity clause.

As for prison reform, the First Step Act gives greater incentives to enter anti-recidivism programs in preparation for release from prison. The number of “good time” days an inmate can earn per year will increase from 47 to 54. And for each month spent in “recidivism-reduction programming or productive activities,” prisoners will be able to receive 10 days of “earned credit,” which can be applied to supervised release or a stay in a halfway house.

“We think it’s a strong package,” says Koch Industries general counsel Mark Holden, who has spent the last half-decade on sentencing reform. “It’s been a real broad, bipartisan effort.” He cited a unique coalition that included young progressives like Cory Booker, D-N.J., but also Republican octogenarian Chuck Grassley of Iowa.

For conservatives, what Holden described as “wasteful spending” was a strong impetus to reform a prison system that has a budget of $7 billion per year, with about $36,000 devoted to each inmate, according to Bureau of Prisons statistics. In a conversation with Yahoo News, Holden pointed to “evidence-based programs” that over time have assuaged conservatives’ fears about the potential impact of reducing the prison population, which stood at a total of 2.3 million people incarcerated across 5,961 state, federal and local facilities. Much of that work took place in states, those much-touted laboratories of democracy. Holden specifically pointed to Texas, which closed eight prisons to no obvious detrimental effect (the state did see a slight rise in violent crime in 2017, but some believe that is due to the decrease in the ratio of police officers to residents). A recent report by the Vera Institute of Justice praised states like North Dakota and Connecticut for adopting progressive concepts from abroad.

While little in the First Step Act is new, it has been a long time coming. President Barack Obama introduced sentencing reform near the end of his second term in office; then, as now, the proposal had support of conservatives dismayed by the growth of the prison population and the inability of the formerly incarcerated to reenter society. What it lacked was support from McConnell, who effectively stifled the bill. “I think that Sen. McConnell understandably did not want to tee up an issue that split our caucus right before the 2016 election,” McConnell ally Sen. John Cornyn, R-Texas, said at the time.

A president from his own party proved too difficult for even the wily Kentuckian to outmaneuver. Trump’s son-in-law and adviser, Jared Kushner, took the cause up as his own, working with its original sponsors, Sens. Grassley and Dick Durbin, to revive a measure that seemed to run counter to the president’s own rhapsodies on law and order. Within days, a president frequently fond of playing sheriff-in-chief will be able to credibly tout himself as a criminal justice reformer fit to be feted by the American Civil Liberties Union.

Politics aside, the First Step Act is an unlikely triumph of sound policy on the nation’s increasingly tribal political landscape. At a time when tweets constitute public discourse, a 149-page bill attracted support from Democrats and Republicans alike. They worked to improve an earlier House version of the bill that did not address sentencing reform. At the same time, supporters worked to assuage the concerns of Republicans who thought aspects of the bill were too lenient.

Critics do remain, on both right and left. “On balance, we would likely still support the legislation,” said Gotsch of the Sentencing Project. Yet she expressed reservations about some of the “tweaks and changes” legislators were making ahead of an expected vote in the coming days. Gotsch cited in particular a push to exclude certain classes of offenders from earned-time benefits, as well as language that would somewhat restrict just how much leeway judges have in straying from mandatory minimum sentences.

DeAnna Hoskins, chief executive of prison reform nonprofit JustLeadershipUSA, was even more skeptical. “I really feel that is not a first step, this is a baby step,” she said, charging that the law would not do enough to correct discriminatory policies in law enforcement and criminal justice, which have tended to disproportionately affect people of color and the poor.

“We are willing to accept incremental steps,” Hoskins told Yahoo News, pointing to several provisions of the bill she found detrimental. These had to do with “carve-outs” that would prevent certain individuals from reaping the proposed benefits of sentencing reform. She worried that algorithmic assessments, which are susceptible to bias, label some individuals as being at a “high-risk” for recidivism, thus making them ineligible for reentry programs. These are the very individuals, she argues, who would most likely benefit from such programs.

Hoskins also points out that in order to have their sentences considered under the newly retroactive Fair Sentencing Act, prisoners would have to petition the relevant court. “Why should they have to petition,” she wonders, “if the law has changed?”

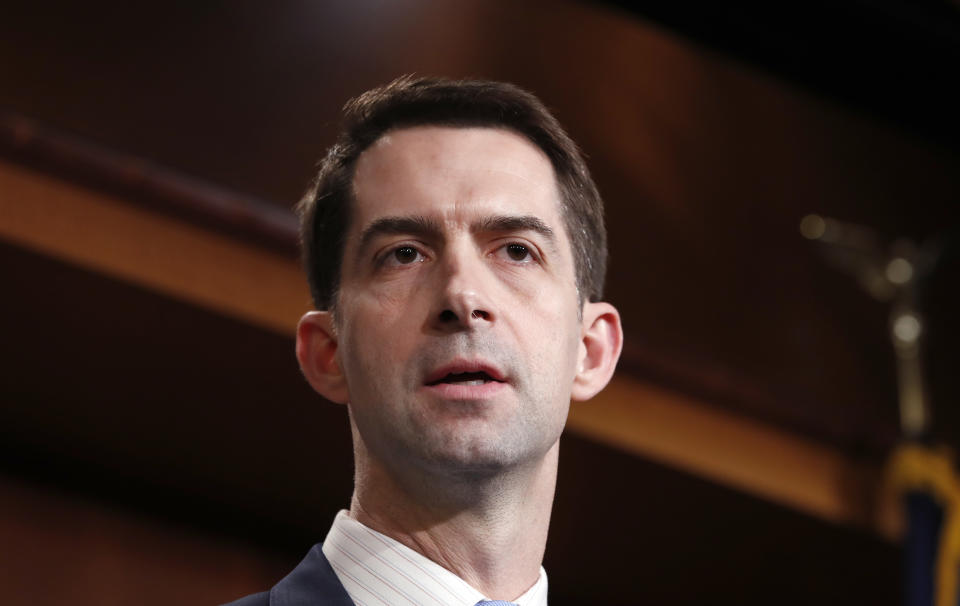

The most vociferous detractor on the right has been Sen. Tom Cotton, R-Ark., who has argued that the United States has an “under-incarceration problem.” That is not a widely shared view; the United States has by far the world’s biggest incarcerated population, as well as the world’s highest rate of incarcerated individuals in proportion to the general population.

Cotton has an ally in Sen. John Neely Kennedy, R-La., but the duo has been a renegade in the Republican conference. In a sign of just how far thinking on criminal justice reform has come since the days when tough-on-crime was practically a Republican slogan, McConnell has hinted that he might vote for the bill himself.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Trump first wanted his attorney general pick William Barr for another job: Defense lawyer

Blackwater Beef anyone? Private security company’s founder now sells a different kind of muscle

Plea deal by Russian agent Maria Butina describes 2016 influence campaign

U.S. intelligence sounds the alarm on the quantum gap with China

Where are Trump’s ’10 terrorists’ who were busted at the border?

Photos: Manhunt for Strasbourg, France, Christmas market attack suspect