When will COVID-19 be over? How Austin doctors, scientists predict the future of pandemic

We've dealt with two years of COVID-19 in Austin.

Is it over yet?

Not yet, but it is shifting from what we experienced in 2020 and 2021.

Toby Hatton, a trauma nurse with Ascension Seton who did his master's thesis in pandemics and pandemic response, says pandemics usually last between three and five years.

"All it takes is one mutation the right way or one mutation the wrong way," he said, to change the trajectory of this disease.

Dr. Amy Siegel, who ran some of the clinical testing for coronavirus vaccines and treatments at Austin Regional Clinic's clinical branch, said that in a year from now we will be in an endemic mode, but "it's not ever going to go away."

"I'm optimistic that we might be nearing the end of the pandemic where COVID-19 is more like an endemic," Siegel said.

Stage 2 guidelines: Austin moves back to looser Stage 2 COVID-19 guidelines, first time since before 2021 delta surge

The difference between pandemic and endemic is that in a pandemic there is active fighting of an illness all the time and that the illness is winning. An endemic is like the flu, in which we have seasonal spurts, but it doesn't control us.

Learning to live with COVID-19

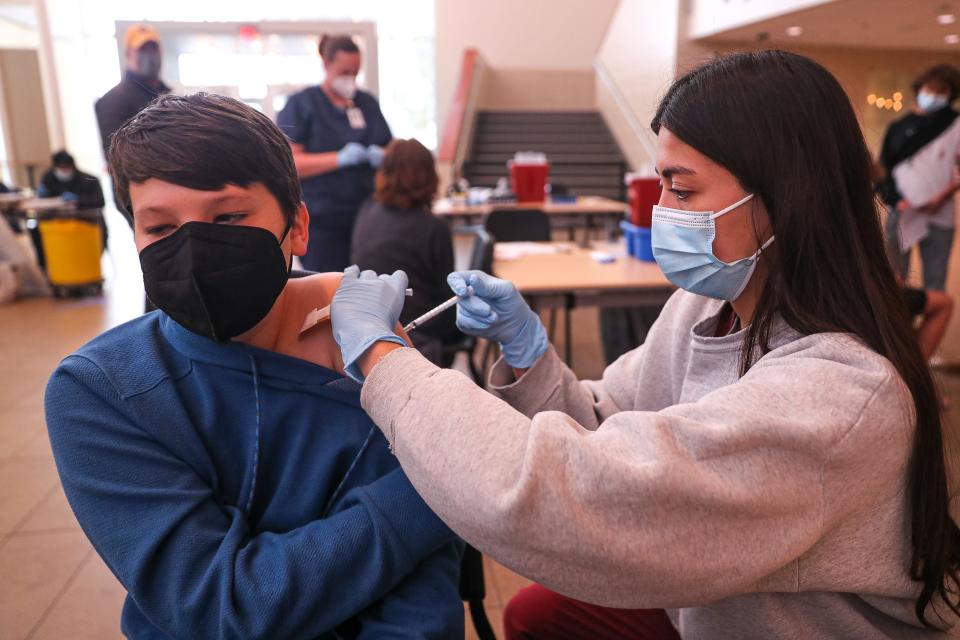

"We have to change our mindset and say this is what we will be living with. We have to get the vaccine to make life as normal as we can," said Dr. Meena Iyer, chief medical officer at Dell Children's Medical Center.

Lauren Ancel Meyers, a University of Texas professor and head of the UT COVID-19 Modeling Consortium, agrees. The consortium has been predicting the trajectory of this disease since it was only known to be in China.

"It doesn't seem likely that COVID-19 is going to be eradicated unless we can come up with a vaccine that is universal and everyone is willing to take it," Meyers said. "That doesn't seem likely."

What is more likely is that COVID-19 "morphs into a more manageable, less severe threat," she said. It becomes something for which we get a yearly booster vaccine and we use new oral medications from Pfizer or Merck or other treatments that are still being developed to lessen the symptoms.

"It doesn't send people to the hospital and people don't die from it, because we are able to manage it more effectively," Meyers said.

Those new oral medications and other treatments, she said, "may be game-changing."

The gift of the omicron variant

"Omicron swept through like no other wave," Meyers said. "We benefit from it with more immunity."

Even people who are still not vaccinated, but got the omicron variant of the coronavirus, now have some natural immunity. It's not as robust as a vaccination, and natural immunity is thought to decease more quickly than the vaccine's immunity.

We might now have gotten to a level of immunity that makes it harder for the virus to mutate.

Omicron also highlighted the gift of the vaccines. Even though people who were fully vaccinated and boosted still got COVID-19, the "vaccines keep people out of hospitals. That is absolutely lifesaving," Meyers said.

When's the next surge?

In the first two years of COVID-19, we have had a surge of cases in summer and a surge in winter in Austin.

Right now, because of the omicron surge, "we have a wall of immunity," said Dr. Brian Metzger, medical director of infectious diseases at St. David's HealthCare.

"If things stay the same, we won't have much of a summer surge," Metzger said. "Hopefully, this thing will revert to more of a coronavirus season, which is late fall and winter. We'll continue to have some degree of surge in late fall and winter."

Meyers does not want us to get complacent, though. She remembers having the same conversation about the possibility of COVID-19 becoming a winter season disease at this time last year. Then people came back from spring break, relaxed and took off their masks, and cases went up. By summer, we were in the thick of the delta surge.

Metzger also cautions against being overly optimistic, even though he said he is feeling more optimistic than ever before in this pandemic. He's cautious because we don't know what a next variant could be like, he said.

Waiting for the next variant

Viruses don't stay stagnant. They mutate all the time. Most of the time, they don't become more life-threatening.

"We need to assume that there will be different strains and every strain will have its own personality profiles," said Dr. Anas Daghestani, the chief executive officer at Austin Regional Clinic.

Omicron caught us by surprise, Meyers said. The next variant could, too.

"It is absolutely possible that we're going to have another variant that evades immunity and infects a large proportion of people," Meyers said.

Her hope is that if that happens, we will have time to know what is coming to build up immunity with new variant-specific vaccines.

Metzger remembers thinking how could a variant be more transmissible than delta, and then omicron came and it was much more transmissible than delta.

"There are not many more things more transmissible than omicron. It's basically measles," which is one of the most transmissible diseases, but he said, "the bar is getting higher and higher for this virus to mutate into something that can jump over this wall of immunity that we've developed."

If this virus does mutate, it's more likely that it will be more immune evasive than omicron, Metzger said, rather than more transmissible. "The antibodies we made to vaccination don't work quite as well as far as preventing symptomatic disease."

Some of it will come down to luck, said Dr. Stanley Spinner, vice president and chief medical officer at Texas Children's Pediatrics & Texas Children's Urgent Care. "What is the next variant? Is it more contagious, is it more virulent?"

Spinner would love to see COVID-19 become more like other coronaviruses, which are common colds and "nothing that puts people in the hospital."

Getting control of COVID-19

The key to getting control over COVID-19 in a world of global travel is to get 70% of the world vaccinated, said Dr. Maryam Ayaz, who works in the intensive care unit at St David's Medical Center. "The entire world needs to be together on this."

In the United States, 65% of the population is fully vaccinated, but in countries like Chad, Haiti, Burundi, Tanzania and Nigeria less than 5% of the population is vaccinated, according to Our World in Data, which compiles vaccination rates from individual countries and the World Health Organization.

"It's so important to vaccinate the world," Meyers said "It is a life-and-death difference in the rest of the world."

The virus, she said, is looking for a vector to multiply. Humans have to not be that vector. Sending vaccines around the world is the only way to stop the variants and the surges, Siegel said.

Even if we cannot get the world vaccinated, we can do things to minimize the spread at home, such as making sure we are vaccinated and up-to-date with boosters, and to practice social distancing and wearing masks again when cases begin to rise and we're no longer in a low-level transmission area according to the CDC, or no longer at Stage 2, according to Austin Public Health.

Meyers likens masks, testing and social distancing to an umbrella. When it's raining, we grab an umbrella.

"When we get to COVID-19 season, we wear masks, we ramp up testing so we can catch people before they show up at school or work," she said. "We come up with ways to protect people at high risk, to mitigate the impact to essential services and even nonessential services, to keep our businesses thriving."

When to get boosted: Do I really need to get a COVID-19 booster? CDC real-world study confirms effectiveness

Regular boosting and testing

Currently, boosters have been recommended for five months after the initial series for the mRNA vaccines and two months after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine. It's possible the next round of boosters will not be recommended until summer, in preparation for a fall COVID-19 season, Metzger said.

When we reach endemic levels, we'll be able to treat COVID-19 like the flu. Each year, we can get a variant-specific vaccine, perhaps even one that is combined with the flu shot. That's what happened with the H1N1 swine flu outbreak in 2009. That vaccine is now part of the typical flu shot.

Ari Rao, Baylor Scott & White Health system senior vice president, chief pathology and lab medicine officer, also would like to see COVID-19 added to the respiratory panel of tests. People will come into their doctor's office or urgent care or emergency room with respiratory symptoms and they will be tested for everything from flu to RSV to COVID-19.

"We'll still have sick people; we'll still have sick people admitted to the ICU, but the therapy is getting better," Rao said.

We'll have therapeutics like the new oral pills from Pfizer and Merck that can treat symptoms if used early in the disease progression. We'll have new treatments once inside the hospital.

"I feel more optimistic than at any other point in this pandemic," Meyers said. "The first year of the pandemic was really dark and very uncertain."

Now we have vaccines, we have the ability to get a test and even test at home, and we have the ability to treat at home and then in the hospital.

"I think we're heading to a more manageable disease," Meyers said.

Mask guidelines: Should I wear a mask? How to understand the new CDC COVID-19 guidelines

Preparing for the next pandemic

Meyers, who spent 15 years studying influenza with the belief that it would cause the next pandemic, said she and other researchers need to revise their models to better track viruses and anticipate their dangers.

"The next pandemic may not be a coronavirus or an influenza," she said. "The kinds of modeling we should be building is a full-range of pathogen threats ... to come up with a better game plan to ensure the right arsenals."

"COVID-19 has been a huge awakening," she said.

In this part of the world, we have also been lucky, Meyers said. COVID-19 and its variants didn't start here, so we could anticipate their arrival a bit based on what was going on elsewhere. We have to continue sequencing the samples of COVID-19 test to detect any new variants that might emerge.

Baylor Scott & White Health system sequences about 100 to 200 samples a week from around Central Texas since October 2020, Rao said. "We've been able to monitor the variants as they pop up."

The COVID-19 that doesn't go away: For when symptoms don't go away, Dell Medical School sets up clinic for 'long COVID'

Ready to move on

"People are saying, 'I'm over it,'" Siegel said. "They are done. They are frustrated. They want their life back."

Everyone has their own comfort levels as well as their own risk factors, Daghestani said. Some people are ready to shed the masks. Some will continue to wear them. Some are ready to go to a restaurant or a crowded public place; some are still using curbside for all their shopping.

"It's OK to be more optimistic and take precautions, but there's no need to panic anymore," he said.

Vaccination remains the key, Hatton said. "The more people we can get vaccinated, the quicker we can get back to a more normal life. ... We need to think about not just ourselves but others."

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: COVID-19: What is the future of the pandemic in Austin