Could UAW victory in Tennessee spread unions across the South?

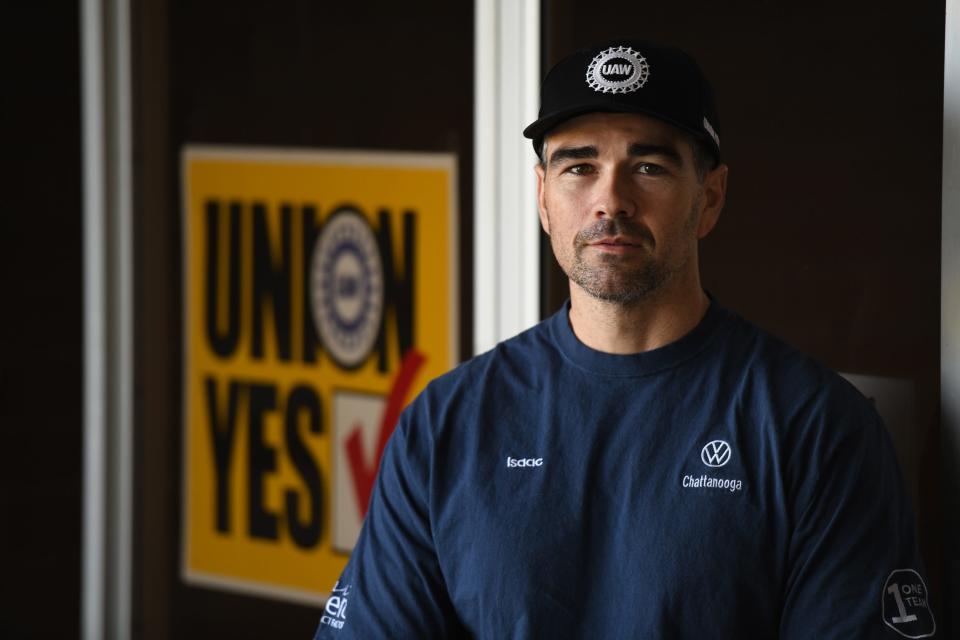

At the Volkswagen plant in Chattanooga, Isaac Meadows works on the line outside the paint shop. The gleaming car bodies, traveling along a path as long as a football field, stop in front of Meadows at a steady clip, and he attaches parts before the car-in-the-making moves down the line to the next worker.

“The work is very entertaining. I enjoy building stuff,” said Meadows, 40, who moved to Tennessee from Reno, Nevada, for a change of pace and found work at VW. “I don’t have any complaints about the actual job itself.”

Meadows, who has worked at the VW plant for a year, does have other complaints. He wants to be paid more. He wants more control over his schedule, when he can take breaks or when he has to work a Saturday shift. He wants more of a voice at the company. That’s why he supports the United Auto Workers' current campaign to form a union at the Chattanooga VW plant.

He's not alone. A supermajority of workers at the Chattanooga plant signed cards showing their support for a union, according to the UAW. Last week, they filed a petition with the National Labor Relations Board for a union election at the plant. In response, President Joe Biden issued a press release congratulating the VW workers.

It's no surprise to scholars and industry experts that this occurred months after a 6-week national UAW strike ended last October with a favorable, new contract for 145,000 employees at Ford, Stellantis and General Motors, including the GM plant in Spring Hill — outside Nashville.

The UAW, a union founded in the 1930s, has now turned its sights to non-unionized, often foreign-owned car plants, many of which are located in Southern states such as Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi and South Carolina.

“It’s a very promising moment,” said Timothy Minchin, a professor at La Trobe University in Australia who studies the U.S. labor movement. "I think the climate is better than it’s been for a long time."

Last year’s strike, and the contract it produced, caught the attention of autoworkers far from Detroit. And Shawn Fain, the UAW’s current president, has shown himself to be a savvier tactician than previous leaders.

"The Big Three strike kind of shed a light on a lot of things," said Ronald Terry, 57, who has worked at Hyundai's plant in Montgomery, Alabama, since 2014 and supports the union drive there. Terry said his wages were far below autoworkers nationally. He also wants more sick days and fewer last-minute schedule changes.

Organized labor has always struggled in the South. Experts believe that across the region, UAW's best chance for a win today is in Chattanooga, although a victory there is far from certain. Twice, in 2013 shortly after the plant opened, and again in 2019, a majority of the VW Chattanooga workers voted to reject the union.

When the decision to unionize at VW in Chattanooga is again put to a vote, workers who publicly support the UAW might change their minds in private. And the forces that kept unions weak in the South could mean a potential victory at the VW plant leads nowhere for the UAW.

Why unions rarely win in the South

The South has often attracted businesses by promising lower-paid workers and fewer unions. The tactic dates back to the late 19th century, when textile mills were lured South from New England and the Mid-Atlantic region.

Unions came to be viewed in the South as an outside force from the North, Minchin said.

Keeping unions out was necessary, many thought, to make the South an attractive destination for businesses.

“The key thing you see in the South is the participation of the local political establishment in trying to keep out the union. And that goes from the governor’s office down to local people,” said Stephen Silvia, a political science professor at American University who wrote “The UAW’s Southern Gamble: Organizing Workers at Foreign-Owned Vehicle Plants.”

States in recent years have offered large subsidies to lure businesses. VW, for example, received more than $800 million in subsidies for its Chattanooga plant from state, local and federal sources.

The funds come with a price. State and local politicians often feel they have the right to tell these businesses how to operate.

“And typically they say, ‘We don’t want a union,’” Silvia said.

Republicans hold power in Southern states, and historically they oppose unions on principle. Unions also generally support Democratic politicians. The UAW has already endorsed President Joe Biden for the upcoming U.S. presidential election. For Republican politicians, keeping unions out, Silvia said, is also a matter of maintaining power and keeping their jobs.

All states in the South, including Tennessee, have enacted “Right to Work” laws. The laws mean even if a union has organized a business, the workers are not required to pay union dues.

“That’s why union density in non-Right to Work states is double that of Right-to-Work states. The union’s stock and trade, its business model, is dues revenue,” said Mark Mix, president of the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation.

In the South, foreign and domestic automakers often choose to locate in smaller towns. Workers in remote locations have fewer opportunities for work. And generous donations to local organizations can build community support for the company. VW, for example, notes that since 2010, it has gifted nearly $10 million to nonprofits in the Chattanooga area.

A new era for unions in the South?

The 2023 strike and the pay raises and other concessions won by the union galvanized Southern auto workers interviewed by The Tennessean. Throughout U.S. history, unsurprisingly, wins by unions have been the greatest spur to the growth of organized labor.

“Even small victories increase the odds that more workers are willing to join. The original unionization of the auto industry happened after a small number of workers at General Motors in Flint won a victory. And the UAW’s recent victory was a really major victory,” said Vanderbilt University’s Joshua Murray, co-author of “Wrecked: How the American Automobile Industry Destroyed Its Capacity to Compete.”

Murray credits Fain, the UAW’s president, with pursuing strategic strike tactics that disrupted the automakers operations. Under Fain, the UAW has also moved away from a top-down approach, which several scholars said was a factor in the union’s defeat in previous elections at the VW plant in Tennessee.

“They take our input, instead of telling us what we need to do,” said Jeremy Kimbrell, 46, who works at the Mercedes-Benz plant in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, one of the other current top priorities for the UAW. Half the workers at that plant, according to the UAW, have signed cards supporting the union.

Last month, the UAW’s executive board voted unanimously to budget $40 million over the next two years to support organizing workers who build cars and batteries for electric vehicles in the South.

“It’s a unified union. After having achieved a major contract, they are seeking to organize the 13 companies that are not unionized,” said Harley Shaiken, a UC Berkeley professor who studies the auto industry.

Where VW stands

VW has remained officially neutral on the UAW union drive in Chattanooga. Half the board of VW, in line with German law, is comprised of representatives from labor organizations.

“We respect the employees rights to decide what’s best for them when it comes to representation. We will put any information out when we see misinformation or false claims,” said Brent Hinson, CFO for VW in Chattanooga.

Hinson noted that the average VW employee makes more than $60,000, which is above the median household income in Chattanooga. The company also pays 84% of its workers health care premiums.

Last year, VW gave its workers an 11% raise, which is in line with the raises the UAW won for the workers it represents at Ford, GM and Stellantis. UAW argues that VW provided that raise in response to the new union contract and as a way to dampen enthusiasm for organizing. Hinson disputes that claim and said the raise was calculated based on several factors, including inflation and local wages in Chattanooga.

Past organizing efforts at VW in Chattanooga have faced public opposition by Tennessee politicians. Last week, Gov. Bill Lee said it would be "mistake" for the workers to union. So far, other local and state politicians, including U.S. Sen Marsha Blackburn who strongly opposed previous unionization efforts at the plant, have not gotten involved in the current organizing drive.

The stakes in the South

Although the latest Gallup poll found 67% of Americans have a favorable view of organized labor, only 10% of U.S. workers belong to a union, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Forty years ago, the percentage of unionized workers was double.

The UAW, even though it can claim a recent victory against Ford, GM and Stellantis, has seen its membership fall like all unions.

The automotive industry has also changed. America's oldest car companies, which have unionized workers, no longer dominate the industry. More men and women who build cars work at non-unionized plants, many of them foreign-owned and many in the South.

If the UAW wants to grow, it has to find new members in the South.

Workers believe they can win

Yolanda Peoples, 41, has worked at the Chattanooga plant for 13 years, almost as long as it has been open. She was in favor of the first two drives to unionize the plant, and she supports the current effort. She wants more control over when and how she has to work. And she thinks the workers have ideas that could make the plant run better.

Peoples said they made mistakes in earlier efforts to convince fellow VW workers to support the UAW.

"I believe we tried to push too fast, instead of getting everybody familiar on how a union works," she said.

As the plant has grown, so has the number of workers. Today at VW she sees more younger workers who are sympathetic to unions. Peoples thinks this time the union will win.

"Based on conversation that we're having in the plant," she said, "a lot of people are on board with getting a union at Volkswagen."

Todd A. Price is a regional reporter for the USA TODAY Network in the South. He can be reached taprice@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: UAW works to unionize VW plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee