Is it possible that no one told Trump about the alleged Russian bounties?

WASHINGTON — The CIA knew. The State Department knew. Senior congressional officials and the British government were briefed.

So how could it be that nobody told the president?

White House officials offered a new wrinkle Wednesday in their explanation of why President Donald Trump wasn't informed about intelligence collected this year that suggested that the Russians were paying the Taliban to kill Americans, even though officials in both the U.S. and the U.K. were aware of the reporting.

White House national security adviser Robert O'Brien said it was the decision of the president's intelligence briefer.

The briefer, a career CIA analyst, "decided not to brief him because it was unverified intelligence," O'Brien said on Fox News. "And, by the way, she is an outstanding officer, and, knowing all the facts I know, I certainly support her decision."

But intelligence is almost always "unverified." And the idea that a career government bureaucrat unilaterally decided to keep Trump out of the loop on the Russian bounty matter — even though he was in regular phone contact with Russian President Vladimir Putin — isn't credible, current and former national security officials said.

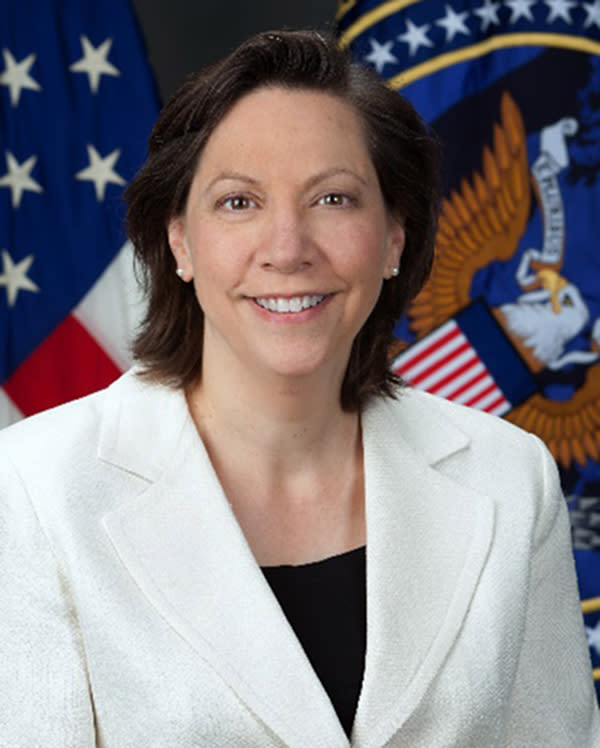

Since April 2017, Trump's lead briefer has been Beth Sanner, a career CIA officer detailed to the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. Her formal title is deputy director of national intelligence for mission integration.

The reporting about possible Russian bounties was included in the president's written intelligence briefing, officials have told NBC News. A senior administration official said it wasn't a significant part of the President's Daily Brief, or PDB, and a number of officials had assessed that the intelligence wasn't conclusive and couldn't be corroborated.

Current and former officials said Trump usually doesn't read his briefing material, so his advisers knew that if Sanner didn't tell him, he wouldn't know about it.

But Sanner doesn't make such decisions alone, current and former officials said. CIA Director Gina Haspel is usually in the room with her, as is the director or acting director of national intelligence — first Dan Coats, then Joseph Maguire, then Richard Grenell, now John Ratcliffe. The national security adviser is often also present, officials said, and they decide together what to include.

The national security team often strategizes long and hard before the Oval Office sessions about what and what not to say, current and former officials said, because team members know certain subjects can provoke an eruption that will send things off the rails.

"From what has been reported about the President's Daily Brief process, choices have to be made about how best to engage the president on a limited number of high-priority topics," said Nick Rasmussen, an NBC News contributor who headed the National Counterterrorism Center early in the Trump presidency.

"But if the material was in the PDB, then every senior national security official in the administration was aware of it, and I find it hard to understand why at least one of those individuals wouldn't have felt compelled to engage the president," he said.

Staff directors at the National Security Council met in March to discuss the intelligence, officials said, but O'Brien opted not to inform Trump.

O'Brien said on Fox that the NSC began developing options to take to the president if the intelligence was "verified."

He added that even though the intelligence was deemed uncorroborated, "we were concerned about it," and U.S. forces and coalition forces in Afghanistan were briefed to "make sure they could have protection."

Critics suggested a troubling scenario. "I believe ... his staff was afraid to tell him about it for fear he would erupt and do something damaging, like calling Putin and tipping him off," said Jeffrey Smith, a former general counsel to the CIA.

Officials at the White House and the national intelligence director's office disputed that assertion. But a few previous incidents have raised questions. In May 2017, Trump revealed highly classified information, apparently by accident, to Russia's foreign minister during an Oval Office meeting, The Washington Post reported.

Also in May 2017, Trump told Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte in a phone call that two nuclear submarines were somewhere in the waters near North Korea, according to a transcript obtained by The New York Times.

In August, Trump tweeted a photograph of an Iranian missile site, which some experts said probably was classified.

Former Trump administration officials have described Trump as extremely difficult to brief, prone to launching into tirades that derail the sessions.

"I didn't think these briefings were terribly useful, and neither did the intelligence community, since much of the time was spent listening to Trump, rather than Trump listening to the briefers," former national security adviser John Bolton wrote in his book "The Room Where It Happened."

Bolton said Trump delivered "rambling lectures" at the briefings, which generally took place once or twice a week.

"He spoke at greater length than the briefers, often on matters completely unrelated to the subjects at hand," Bolton wrote.

Download the NBC News app for breaking news and politics

It is the second time in a few months that Trump or a White House official has cited the actions of Sanner. In response to criticism that Trump failed to act on warnings about the coronavirus that were included in his intelligence briefing materials more than a dozen times in January and February, Trump tweeted that he was first briefed Jan. 23 and that his briefer portrayed the virus as "not a big deal."

In a tweet Wednesday, Trump called the reports of Russians' paying bounties to kill Americans a "made up Fake News Media Hoax started to slander me & the Republican Party." He added, "I was never briefed because any info that they may have had did not rise to that level."

Some Republican lawmakers briefed on the intelligence say that if it is verified, it merits a strong response from the U.S.

By calling the intelligence "unverified allegations," the White House is "hiding behind the language of law enforcement to justify their gross mishandling of the intelligence they were provided," said Smith, the former CIA lawyer, who is a Trump critic.

He and other intelligence experts said intelligence is rarely "verified." Intelligence analysis calls upon professionals to make their best judgments often based on fragments of secret information. Former CIA Director Michael Hayden used to say, "If it was a fact, it wouldn't be intelligence."

The CIA never "verified" that Osama bin Laden was living in a compound in Pakistan — only the Navy SEALs did that, after they shot and killed him.