What could happen if Mecklenburg County closes its Juvenile Detention Center?

We pay. They pick.

In this special report from The Charlotte Observer, we looked at the city's dollars and where they're going. The city's recently approved 2023 budget makes provisions for housing, pay raises and parking, and some are optimistic about what changes this could bring. But for some city employees, it's been a hard living. Explore this reporting package for insight on how Charlotte is spending its money, and what changes might be on the horizon.

See how Charlotte and Mecklenburg budget funding could impact your life, pay and commute

From a hotel, this Charlotte city worker dreams of owning a home

What could happen if Mecklenburg County closes its Juvenile Detention Center?

What do Mecklenburg County employees make? Check out our public salary database

How much do Charlotte public employees earn? Search our salary database.

The Mecklenburg Juvenile Detention Center is quiet, its walls painted white, stains streaking random doors, and broken tiles with dirt and more stains ground into the floor.

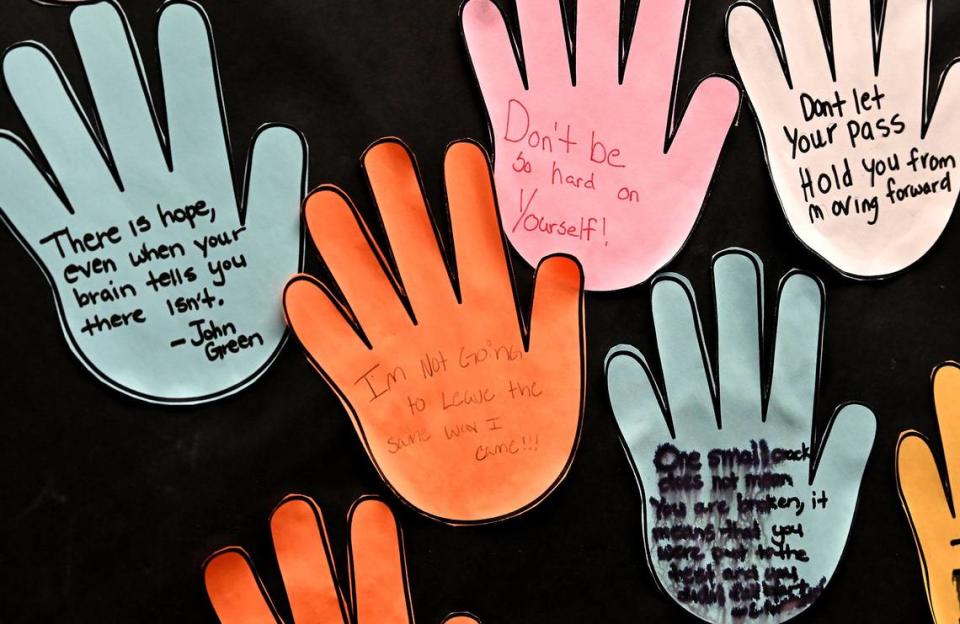

However, one room stands out. Once a week, the teens visit the room: the library.

Here they walk into a room so colorful it doesn’t seem to belong in the building at all. The room is built with bricks painted blue. The carpet also is blue, with the occasional colorful stripe. Books and posters line the walls. A few tables dot the floor, and even more books fill the carts and stands.

By Dec. 1, the library — a seeming oasis inside a detention center — could be gone.

If county commissioners approve County Manager Dena Diorio’s $2.1 billion budget plan this month, Mecklenburg would end its three-year contract with the state and close the facility. About 90 vacant jobs would be frozen, and existing staff would be moved to the county’s uptown jail, where an ongoing staffing shortage has prompted safety concerns by the state.

In a related move, the uptown jail would reduce its federal population to 250 — costing the county $16.7 million in reimbursements from the U.S. government.

Closing the juvenile facility and freezing the open jobs would help mitigate the loss of federal funds, Diorio said, but the county would still be responsible for $4.5 million annually.

Making the proposal to close the juvenile facility wasn’t easy, but “it made sound financial sense” to end a “non-mandated function,” according to Bradley Smith, a spokesman for Sheriff Garry McFadden’s office.

As of May 27, the detention center housed 62 juveniles. If the facility closes, any remaining juveniles will be moved out of Mecklenburg — and some could end up as far as three hours away.

Some advocates for the youths say such moves could have detrimental effects.

“Best practices for children is to be again in the community where their parents have unfettered access to them, even when they’re in a facility,” according to Kristie Puckett Williams of the ACLU of North Carolina. “So if a parent wants to see their child, they should be able to go see that child.”

‘The hope of possibility’

Felicia Wilson and Kim Good run the detention center’s library. Their goal is to provide hope and an education to the teens in the center.

Wilson and Good go beyond checking out books to the teens. A few weeks back, they taught astronomy to the teens and invited a NASA engineer to speak to them about career opportunities. They founded a book club, and filled book shelves with poster boards about prominent Black historical figures the teens researched through the library. Perhaps the library’s most popular program is slam poetry.

The librarians say ever since they started slam poetry nights, they’ve been a hit with the youths.

“This is more than a library,” Wilson said. “This exposes them to the possibilities that they can pursue once they leave this facility. We give them more than reading, we give them hope, the hope of possibility.”

On average, 60-70 books are checked out of the library each week, they said.

The library, and its librarians, are just two of the many resources the teens stand to lose if the center closes.

Advocates worry the teens also will lose access to Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools’ high school curriculum, which is taught inside the detention center, and a horticulture trade program that offers an opportunity to learn a trade and work inside a greenhouse.

Advocates, the N.C. Department of Public Safety, and the African American Caucus of the Mecklenburg County Democratic Party have strongly opposed the proposed closure. But the sheriff and county manager argue it is necessary to make up for a lack of staff and the loss of federal funding.

Cut off from resources

The Detention Center, once known as Jail North, began juvenile operations in 2020 and is one of 12 such facilities in the state. It’s also North Carolina’s largest with 72 beds. The closest facility of comparable size is in Cabarrus County, with 62 beds and more than a 30-minute drive from the Charlotte juvenile center.

But Puckett Williams, the state ACLU official, says moving the youth out of their communities could have negative consequences for them, their families, and their rehabilitation.

If McFadden and the county go through with the closing, Puckett Williams said they should consult with advocates and stakeholders on the best way to take care of the youth they will be moving.

Maria Macon, a founder of the Mecklenburg Council of Elders, runs a juvenile court diversion program with the Charlotte nonprofit. The program offers free classes, such as anger management, fitness, and career skills, to at-risk youths.

Macon said she is concerned that youths will be unable to access the program if the detention center closes.

“Our concern is that the closure ... may mean that the youth that we currently serve from there that are on ankle monitors will no longer be assigned to our juvenile court intervention program,” Macon said. “And, that the opportunity for them to be mandated to some of our other classes in the program will be lost.”

NC offers options

County Commissioner Mark Jerrell, who represents District 4, said the county has limited options and “tough decisions” must be made.

“I’m sensitive to the needs of our sheriff, the concerns around staffing, the availability for staff for Jail Central,” he said. “Their staff has been stretched really thin, throughout the pandemic.”

However, the needs of those in the detention center need to be considered as well, he said.

“So you have these juveniles that have access to services here in Mecklenburg County that are important for reentry,” Jerrell said. “And so what would be the unintended consequences if they don’t have access to that? And then you think about the inability of the family to provide the needed family support for them as well.”

Jerrell said that while he believes providing this care is a state function, he thinks the county needs to weigh the alternatives presented by the state before making a decision on whether or not to close the center.

In a letter last month, William Lassiter, the deputy secretary of NCDPS, urged Mecklenburg commissioners to reconsider the proposal, saying that without the Charlotte facility, NCDPS would have difficulty finding space to house juveniles in custody — especially close to home.

He offered three alternatives: extend the county’s contract with the state until the end of June 2023; transition the center’s operations from the Mecklenburg Sheriff’s Office to another county entity; or allow the state to lease the facility and operate it.

Jerrell said he thinks allowing the state to lease the facility could be the “most viable” option.

“From my understanding (it) would allow ... those who are detained to be able to continue to have access to the resources that we have here in Mecklenburg County, and make it much easier for them from a reentry standpoint,” he said.

Jerrell said commissioners are hopeful to come up with a solution before a straw vote on the budget takes place June 15-16.

Commissioners are expected to adopt the new budget June 22. The new fiscal year begins July 1.