Corruption, Ukraine and Russia

Prior to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, certain commentators maintained we shouldn’t get involved because the Ukrainians were corrupt, and thus somehow deserved in part what happened to them. Since they chose not to run their country on the pristine standards we exemplify, any moral obligation we might have otherwise felt was seriously compromised. The Hunter Biden scandal was just the tip of the iceberg.

Several thoughts have occurred to me. The first is the definition of “corruption.” Life as we live it is largely an ongoing set of quid pro quo. This for that. You do something for me, and I do something for you. If I go to the store and pay $100 for a cart of groceries, nothing is amiss. But if I have a friend running the cash register, and he neglects to ring up all my items, such that I walk out only paying $75 and later slip him a ten to show my gratitude, we now have corruption. If I bribe a judge, or prosecutor, or anyone else to evade the law or my responsibilities, that is corrupt. In the unceasing attempts to force President Donald Trump from office he was accused, in a famous phone call to President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, of offering arms in exchange for an investigation of the aforementioned Hunter. That was held to be an example of corruption rising to an impeachable offense.

A second thought is how often corruption is a matter of law and definition. If I go to my congressman and offer him $10,000 to vote a certain way, that is a bribe, and unlawful. If I get together with others who have a similar interest in legislation, and form a political action committee, and offer campaign contributions for supporting our interests, that is as pure as the driven snow. The intent is the same, the result is the same, but the law has been observed.

Thirdly, and from personal observation, the nations formerly part of the Soviet system are corrupt from top to bottom, and always have been. Bonnie and I were in Russia in 1979. Our official Intourist (KGB) minder warned our group that participating in corrupt practices, such as exchanging dollars for rubles on the black market might get us an all-expense paid extension of our stay in the USSR in special camps in Siberia. Temptation was rife, since officially one ruble cost $1.50, and on the easily accessible black market a ruble cost about 30 cents. So let's say we wanted to buy a traditional Russian fur hat at the GUM department store on Red Square in Moscow. 20 rubles was the price tag, costing us officially $30. With black market rubles the cost would have been $6.

Fast forward to 1990, when I led a tour. What a difference 11 years made. It was still the USSR, but now my minder not only did not threaten us with exile if we bought black market rubles, she showed me how to do it. The security guard in our hotel was the source, with rubles at one third the cost of the official exchange. We brought back some good stuff cheap, especially since the official costs in the workers’ paradise were set artificially low.

In Lithuania in 2012 while I taught there, students informed me that to get good grades in the government schools, you often had to pay bribes. I could have made a lot of money, and professors there, like all poorly paid professionals, relied on subterranean income to make ends meet.

Somehow I cannot get too upset over corruption in Ukraine when it is universal. Ironically, one of the reasons the Ukraine army has done so much better than was thought, and the Russian so much worse, is the pervasive corruption in the Russian army — tires going flat from neglect while the money to replace them, or properly maintain them, went into many pockets.

Finally, I don’t think those of us who live in a smudged pot should call the kettle black.

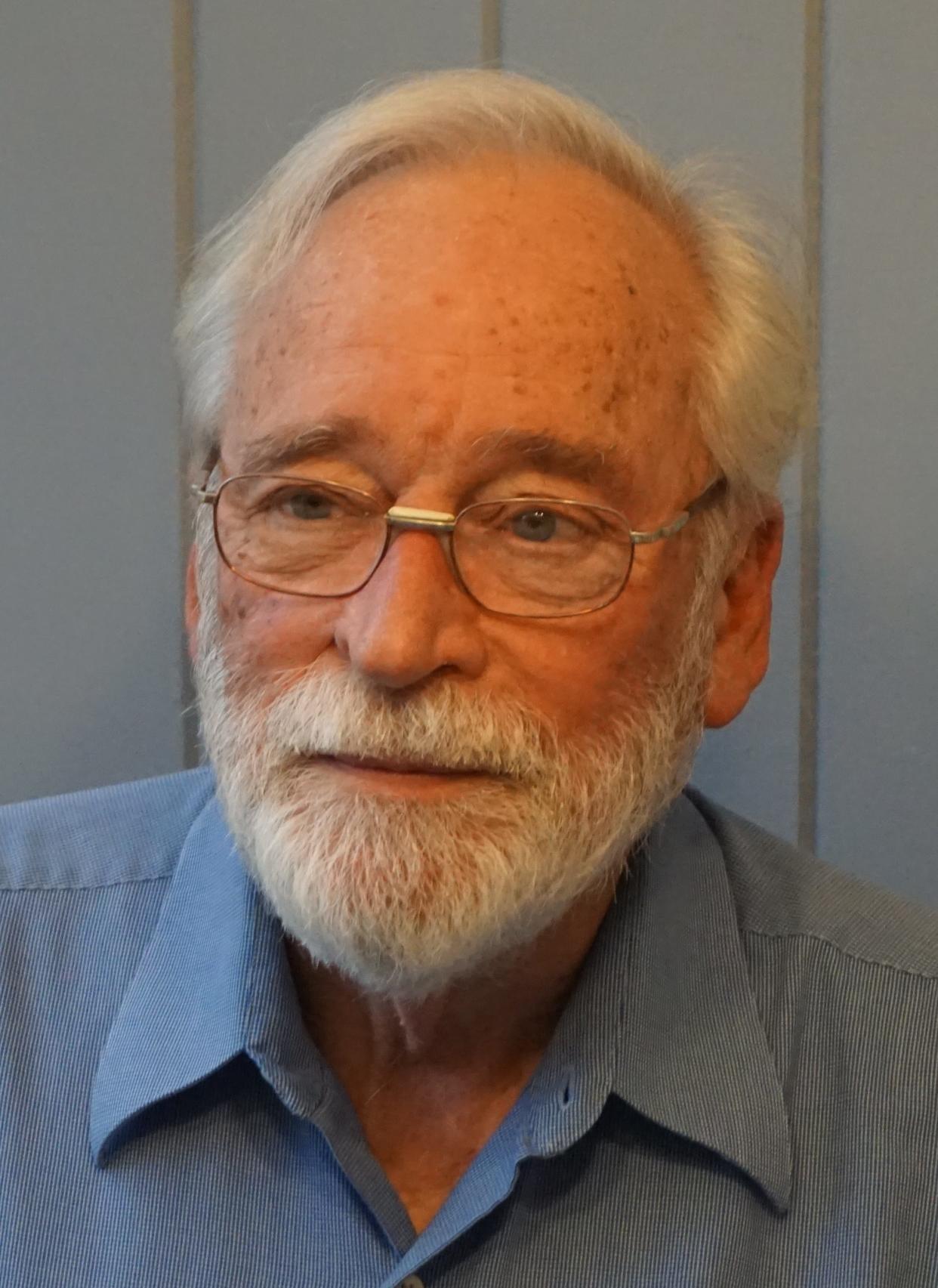

Charles Milliken is a professor emeritus after 22 years of teaching economics and related subjects at Siena Heights University. He can be reached at milliken.charles@gmail.com.

This article originally appeared on The Daily Telegram: Charles Milliken: Corruption, Ukraine and Russia