Coral reefs in Florida Keys hit hard this hurricane season, but there are signs of recovery

Out on the water's surface, floating above the site of a coral nursery was the first sign of trouble: a tangled mass of line, buoys, lobster traps, and debris.

A coral restoration team from Florida's Mote Marine Laboratory was checking on its underwater nursery for the first time since Hurricane Irma brought 140-mph winds to the Keys, and things didn't look promising. The team of scientists grows coral, which is then planted out on reefs decimated by global warming and other human abuses.

SEE ALSO: Before and after photos show Hurricane Irma's devastation in the Caribbean

"Right off the bat we thought, 'Oh it's going to be completely destroyed," said Erich Bartels, a Mote staff scientist. While the infrastructure, including the PVC trees where corals hang like drying laundry, survived the storm, much of the vibrant coral within the 60-by-80 meter site did not. Whipped up sand and tangled fishing gear had harmed the delicate coral.

Image: Joe Berg / Way Down Video via Mote Marine Labaratory

Image: Erich Bartels/Mote Marine Laboratory

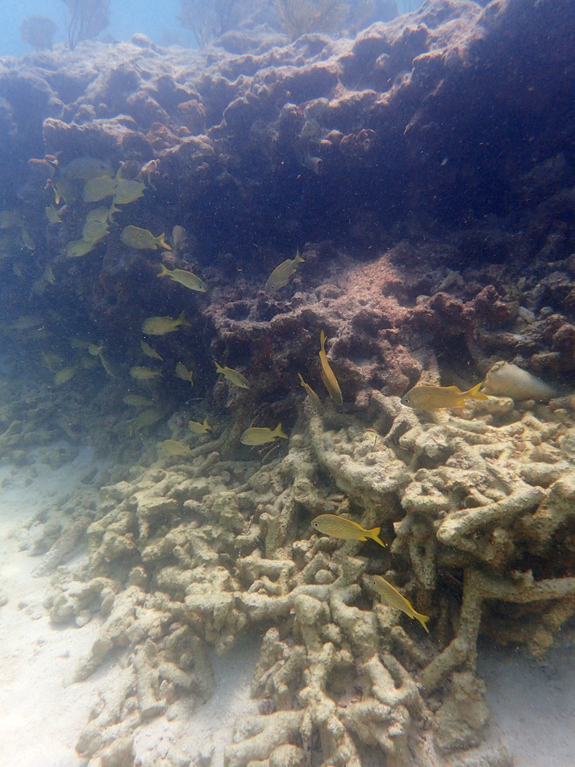

The Category 4 storm left the Florida Keys bruised and battered in early September, but it's not just the land, and its buildings, roads, and trees, that took a beating. Under the sea, the depleted coral reefs are also worse for wear, along with the underwater nurseries conservationists are growing in hopes of replenishing the Keys' once healthy reefs.

The reefs are vital for the Florida coastline because the calcium carbonate structures act as a buffer from powerful waves. They're also important for the economy, as the sea life the reefs support helps feed the state and reel in tourists.

Globally, restoring coral reefs is taking on new urgency as more frequent and severe coral bleaching events kill reefs that are less tolerant of unusually high water temperatures.

"We can only begin to imagine how much more severely Irma would have damaged the Florida Keys without our coral reef shield," Mote's public relations manager Shelby Isaacson wrote in an email.

Image: Erich Bartels/Mote Marine Laboratory

Restoration groups like Mote and the Coral Restoration Foundation (CRF), which had evacuated the area before landfall, are just starting to get back to work and do preliminary assessments of their nurseries and the reefs they support.

"It’s been tough to go back and see some of the reefs, because they’ve just been completely changed," said Jessica Levy, reef restoration program manager at the Coral Restoration Foundation (CRF). "The sites that we’ve seen are pretty barren, they've lost out-planted corals, they've lost natural corals, a lot of the soft corals. We’ve seen the ledge of the reef just collapse."

Image: Erich Bartels/Mote Marine Laboratory

Image: Jessica Levy/Coral Restoration Foundation

While the coral at the Mote nursery off Big Pine Key saw high mortality, two of CRF's underwater nurseries off Tavernier and Key Largo fared better. Still, CRF doesn't know the fate of two other production nurseries farther south because weather conditions have made it difficult to check.

Coral restoration groups have been working for years in Florida to combat decades of damage to the reefs, some of it, like coral bleaching, caused by climate change, some by overfishing, anchoring, polluting, and pathogens. Similar restoration projects are happening around the globe, and perhaps the most well-known is set along Australia's Great Barrier Reef, large swaths of which have been left bone-white and stricken with disease due to rising water temperatures.

This was the first time both Mote and CRF's nurseries faced such a powerful storm. They had weathered tropical storms before, but nothing like Irma. The fact that their infrastructure survived, even if all the corals didn't, was heartening.

"We were in the direct path of the eye, we were in what they call the 'dirty side.' It was about as big of a test that we could be given," Bartels said.

Image: Conor Goulding/Mote Marine Laboratory

Another bright spot for Mote was its Summerland Key land-based nursery and gene bank, which opened this year and was built to resist Category 5 storms. The Elizabeth Moore International Center for Coral Reef Research & Restoration protected 30,000 coral fragments from the storm.

The coral living in shallow, long water tanks called raceways outside the facility were brought indoors just before Irma. Generators helped control the temperatures so the coral did not get exposed to hot water that could cause coral bleaching. While equipment left outside got beat up, the building — and coral sheltered inside — survived.

Image: Mote Marine Laboratory

Image: Mote marine laboratory

Image: Mote Marine Laboratory

Mote had aimed to plant 25,000 of its nursery corals on reefs this year, while CRF planned for 10,000. Both projects may be delayed a bit due to the hurricane, but the organizations are still optimistic about accomplishing their goals.

"I think at this point this work is needed now more than ever because we’ve seen what storms like this can do," Levy said. "This isn’t like we took a hit, we’re gonna stop. It's we took a hit, and we’re gonna keep going."

Both Mote and Coral Restoration Foundation are fundraising to rebuild after Irma.

WATCH: 5-foot robotic snake is designed to find the source of pollution in contaminated water