Conspiracy theorist blames Brazil floods on baseless 'magnetic shift' claim

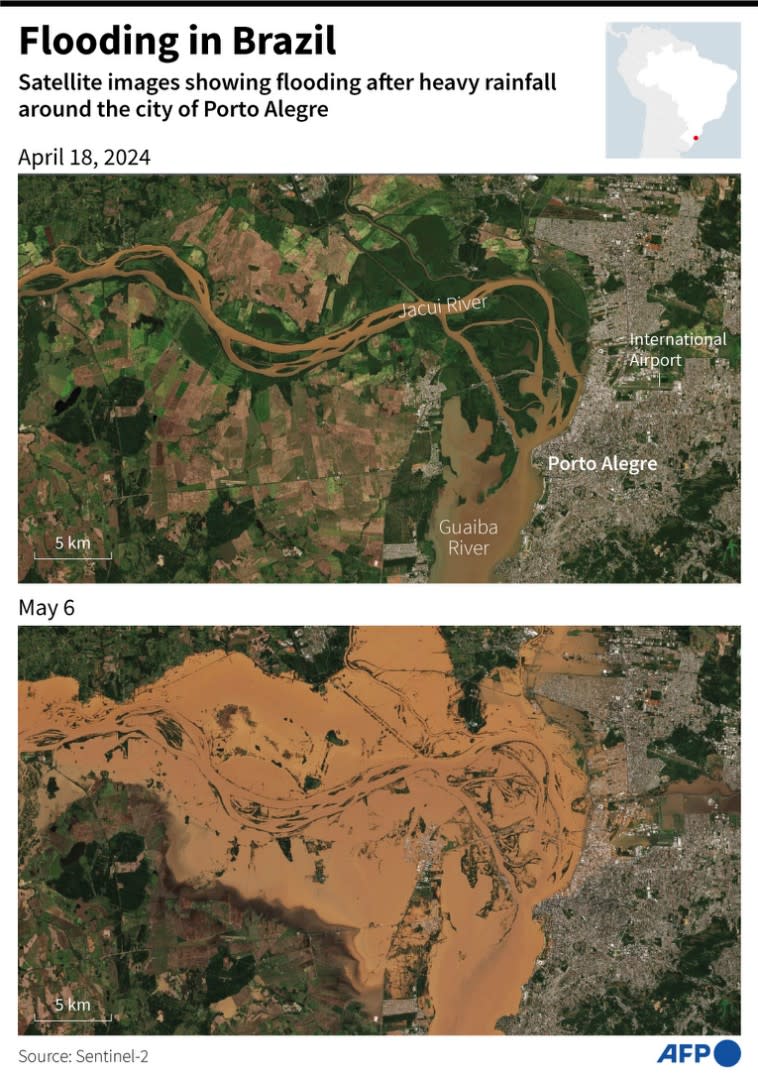

As severe floods struck southern Brazil, killing scores and displacing nearly two million people, an account on X claimed the extreme weather event was triggered by the shifting of the planet's poles. But experts say there is no evidence linking Earth's magnetic field to global warming; on the contrary, established research shows human-induced warming has led to higher levels of precipitation in regions including Latin America, and will continue to do so according to climate models.

"The worst floods in South Brazil. The weather keeps getting more and more intense as predicted by the shifting of the poles and the decreasing of the Earth's Magnetic Field," a May 2, 2024 post on X says.

The same blue-check account, which has more than 70,000 followers, has spread similar theories about extreme weather events in widely shared posts.

Nearly 400 cities and towns have been affected by torrential rainstorms in the state of Rio Grande do Sul.

Experts link the historic deluge to climate change exacerbated by the El Niño weather phenomenon, which can naturally impact precipitation levels (archived here and here).

In the aftermath of the floods, the country experienced a surge in related conspiracy theories, some of which AFP has debunked in Portuguese.

But experts told AFP that no link exists between magnetic poles and climate change, while scientists in Brazil have been studying the impact of anthropogenic warming on rainfall for decades.

Against principles of physics

"There is no scientific evidence whatsoever that ties global warming to either shifts in the magnetic poles or a reduction in the Earth's magnetic field strength," Ingrid Cnossen (archived here), independent research fellow for the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) space weather and atmosphere team, told AFP on May 14.

A spokesperson for NASA's Langley Research Center (archived here) told AFP on May 13 there is no "link between the movement of our magnetic poles and climate," and pointed to an article (archived here) on NASA's website debunking the theory.

The movement (archived here) of liquid iron and nickel buried deep below Earth's surface generates its magnetic field (archived here) -- that movement is what makes our planet's magnetic poles shift (archived here), which eventually completely flip locations every 300,000 years or so. Animals that rely on the Earth's magnetic field for navigation, such as birds or sea turtles, could get temporarily disoriented by the shift.

"While that may sound like a big deal, pole reversals are common in Earth's geologic history" with no evidence of major changes or species extinctions contrary to what "doomsday" scenarios often allude to, NASA writes in its blog post.

The shift also does not happen overnight, the space agency adds, but hundreds or thousands of years.

There is no evidence that our climate has been significantly impacted by previous magnetic field excursions within at least the last 2.8 million years, according to NASA.

Additionally, NASA scientists note that there is no known physical mechanism capable of connecting weather conditions at Earth's surface -- such as atmospheric conditions -- with electromagnetic currents responsible for the shift of poles.

Carlos Nobre (archived here), who heads Brazil's National Institute of Science and Technology for Climate Change (INCT), listed what scientists believe is behind the disastrous recent rainfall: a low-pressure system has been blocked by a high-pressure system in the center-west and southeast of the country, causing cold fronts to linger over the region even as water vapor coming flowing in from the Amazon contributed to historic downpours.

Global warming aggravated the situation, Nobre told AFP for a previous story, adding that "the warmer atmosphere can store much more water vapor, fueling more frequent and intense episodes of rainfall that lead to disasters like this."

Convergence with climate models

Lincoln Muniz Alves (archived here), climatologist at Brazil's National Institute for Space Research (Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais), and a United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) lead author, agreed. "The tragedy in southern Brazil has a well-established cause and consensus among climate experts," he said.

The broader implications of these weather events are tied to global climate change, he told AFP on May 9.

"The increasing severity and frequency of such occurrences are likely linked to the planet's rising temperatures, although more detailed attribution studies are necessary to confirm this," he added.

Chou Sin Chan (archived here), a weather modeling researcher and an IPCC lead author, told AFP on May 10 that "global and regional climate models' projections of the future climate have shown an increase in precipitation, with high confidence, in the areas south of Brazil, Uruguay, and north of Argentina."

The IPCC also noted in previous reports (archived here and here) "significant increases in precipitation" observed in the region in the past.

João Paulo Brêda (archived here), environmental engineer specializing in large-scale hydrology, told AFP on May 9 that the "exceptional event that is happening now converges to the climate models' predictions."

AFP has debunked other claims about extreme weather events in other regions and their ties to climate science, here and here.