Why Cincinnatians are worried about this Connected Communities zoning overhaul plan

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Cincinnati's controversial plan to overhaul its zoning code, known as Connected Communities, aims to offer a sweeping solution to the city's housing shortage.

Years in the making, the proposal goes to its first of three public votes Friday at the city's planning commission meeting.

More than 300 people wrote letters to the city in support of the plan, according to public documents reviewed by The Enquirer.

But citizens in recent public meetings say they don't like it. And an Enquirer survey found that the city's influential neighborhood community councils have major qualms and feel left out.

Despite the city's two-year long engagement process, Cincinnati residents argue there's not been enough information provided.

They're worried about new housing without parking.

They fear single-family homes will be demolished for multi-family buildings.

They're concerned more renters will move into single-family areas and won't invest in the neighborhood.

They say they already feel burdened by failing infrastructure like sewers, flooding and lack of street paving.

And in neighborhoods where there's already concern about absentee landlords, this plan could allow for more.

Over 50% of Cincinnati's community councils that answered The Enquirer's survey formally oppose the plan and 42% are still unsure. There's even a petition signed by over 300 residents across more than 30 neighborhoods calling for a pause on the vote and more time to review the 150-page draft legislation, released on April 11.

None of these concerns are things to worry about, city officials said. All of these issues have been taken into consideration by the planning department. Cincinnati City Councilman Reggie Harris, the legislation's champion, said this is a long-needed update of the zoning code that simply allows for more density like all big cities.

More: Listen to That's So Cincinnati Connected Communities zoning remake 'a return to Cincinnati's very dense past'

So what's the truth?

The one thing that consistently comes up from residents is: What will happen to my street? However, because the plan ultimately depends on a developer wanting to build, there's no way to know the answer. And that has stoked the fear that city officials are now hearing.

"There is no substantial proof that developers are going to lower rents, nor will they care about the complexion of our neighborhoods," said survey respondent Pricilla Elgersma, a Mount Washington Community Council board member.

The Enquirer took a deep look into the proposal and held conversations on Connected Communities with Harris, Mayor Aftab Pureval and neighborhood leaders. Here's our explainer on the plan.

What is Connected Communities?

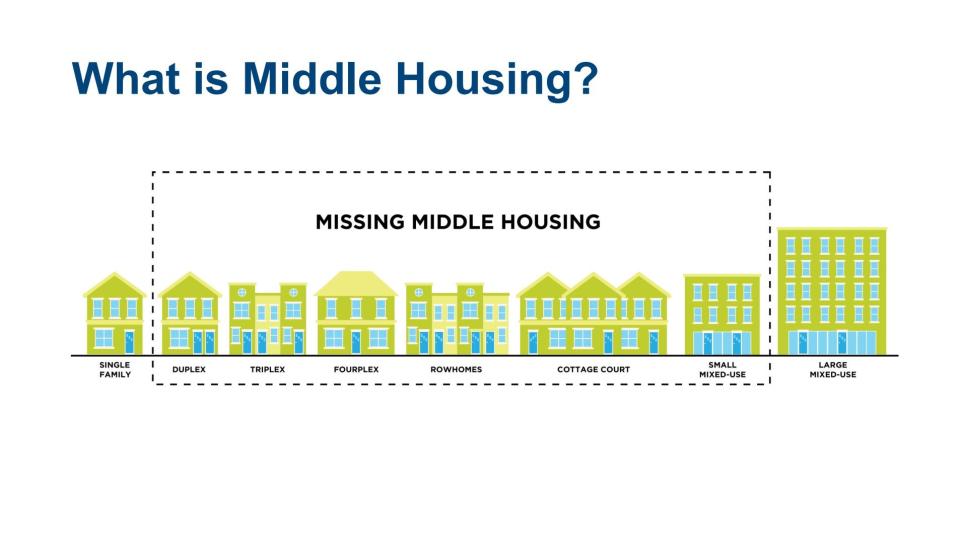

Simply put, it's a zoning code change targeted at adding what the city calls "middle housing" to neighborhood business districts and the streets closest to them, and along transit corridors. Middle housing, everything from duplexes to rowhomes to small mixed-use buildings, exists in Cincinnati already, but city officials and planners argue the city needs more.

And, without this housing, they say, the city can't grow.

For developers, this change would mean they can construct buildings with more units and less parking without having to ask the city for permission. Right now, the rules favor single-family homes, and if a developer wants to do something different, it takes months of zoning requests and hearings.

This is great for developers because it lessens the lag time for development and helps keep construction costs low. But if you live there, that same lengthy process gives the citizen plenty of time to understand what's being built and provide feedback. Citizens following the possible change aren't against the idea of shortening the process, they just don't want it to go away altogether.

What Pureval and Harris say

Pureval and Harris understand why there's pushback and they think they're prepared for it.

"This is really, really hard," Pureval said. "The reason why we are in this position where we have the highest rent increases in the nation is because we have not substantially touched our zoning for a very long time."

Even with the opposition, Harris and Pureval expect the plan to pass in city council in early June and they don't want a delay.

Pureval sees the opposition as resistance to change, not necessarily the plan itself.

"They want their neighborhoods to be the way they are today," Pureval said. "And change is very difficult. But if we are to take significant strides on making sure that people have access to housing at different price points throughout the city, then we have to make these hard decisions. We need action right now."

What community councils say

Cincinnati's over 40 community councils serve as the link between the local government and the individual neighborhoods that make up the Queen City. All volunteer-based, they regularly deal with zoning issues related to development projects in their areas. But according to The Enquirer's survey, over 70% of Cincinnati's community councils claim that the city's planning department or an elected official never formally contacted them about the proposed legislation.

The city disputes this and says they did reach out multiple ways: There was email outreach by the planning department and the mayor, open Zoom meetings with the mayor, invitations to in-person engagement sessions at recreation centers, and detailed presentations to Invest in Neighborhoods, a nonprofit that works with community councils. They called the amount of engagement they did "unprecedented."

One thing the city didn't do? Formally present Connected Communities to community councils without being asked. "That's an unreasonable expectation for [them] to have," Harris told The Enquirer. Yet that's what people wanted.

So far, no community councils fully endorse it. This reflects the conversations held at recent public meetings by the city's planning department. Some neighborhoods are arguing for an opt-in approach to Connected Communities. Why not, they ask, allow for zoning changes in areas that want increased density or more housing?

Even high-density neighborhoods like Over-the-Rhine and Clifton aren't convinced this will work. Years of investment in both areas have led to rising rents and home prices, problems with parking, and in some cases, displacement.

Mike Cheetham, president of the Mount Lookout Community Council, put it this way to The Enquirer: "Why has there been little to no direct engagement with community councils during this process? Our residents crave information on this proposal." He added, "A formal presentation from a city representative with a Q&A would have gone a long way."

Roselawn Community Council President Annie Ruth Napier said: "The process of engaging our community is faulty."

Who supports the plan?

This doesn't mean there isn't support for Connected Communities. Many of the city's community development corporations, including HomeBase, which advocates for them, outright support the plan. So does Metro, the Cincinnati USA Regional Chamber, the Human Services Chamber of Hamilton County, Habitat for Humanity, the University of Cincinnati, UC Health, Cincinnati Children's and the American Planning Association, among others.

Plenty of average residents back it, too.

Madisonville resident Kerry Devery wrote a letter in support, saying the change is "necessary" and "long overdue."

"If something like Connected Communities had passed 10 to 20 years ago the current affordability crisis would not be as severe as it is now," Devery said.

Logan Stryker of Clifton Heights wrote: "Time to drag Cincinnati, kicking and screaming, into the present."

Everyone else is doing it

Experts say overly restrictive zoning laws from the mid-century have contributed to a national decrease in housing construction. Like in many American cities, in Cincinnati it's illegal to build anything but detached single-family homes in most of the city.

That's why other cities are trying to implement major zoning changes to address their housing shortages. Since 2017, over 130 municipalities have tried − many successfully − to overhaul their zoning codes, according to the University of California at Berkeley. Columbus is doing it (and on a similar timeline to Cincinnati's), and so is Louisville and Pittsburgh.

Minneapolis was one of the first metropolitan areas to push major zoning reform − and took it as far as ending single-family zoning altogether. According to recent research done by the Pew Charitable Trusts, from 2017 to 2022, Minneapolis added 12% to its overall housing stock and the majority of residential units built were in apartment complexes with 20 or more units. Rents also rose just 1% in those five years.

But a recent national study done by the Urban Institute revealed that cities that enacted major land-use reform increasing density between 2000 and 2019 saw an average 0.8% increase in their housing stock three to nine years after passage. The majority of those units were reserved for people with above-area-median incomes. According to census data, the median Cincinnati household brings in $48,000 annually.

Seeing the benefits of Connected Communities will take more time than that. "This is a decade vision," Harris said.

Where will people park?

One of the biggest criticisms is the plan's elimination of parking requirements for developers. Opponents worry that will mean new residents will be forced to park on the street or in existing surface lots. But Connected Communities still allows developers to build parking in many cases, if they want. There's just no minimum requirement for spaces.

What's not *technically* included

Even opponents of this plan agree the city's 100-year-old zoning code should be updated. It's often cited as one of the reasons why Cincinnati is so segregated. Mayor Pureval touts Connected Communities as a way to increase affordability throughout Cincinnati's neighborhoods and reduce concentrated poverty.

Affordable housing

Unlike in other cities, the plan purposefully leaves out affordable housing solutions.

Instead, this plan doubles down on ensuring developments that received Low-Income Housing Tax Credits, also called LIHTC, are processed more smoothly and quickly. But right now, the city is under investigation by the federal housing department for the alleged misuse of federal funds to steer low-income projects to poor, Black neighborhoods. Areas like the West End worry Connected Communities will only exacerbate the issue.

Pureval and Harris say federal oversight provided by the LIHTC program is more than the city could do on a project-by-project basis.

Homeownership, demolition protections

It also doesn't include direct plans for increasing homeownership, something that comes up regularly at city council meetings. Cincinnati is a city of 62% renters. Citizens think Connected Communities is largely about adding more renters because developers can build more units if they target renters. The city disagrees.

City officials claim Connected Communities will help boost homeownership because it includes a plan to legalize the construction of rowhomes in certain single-family-zoned districts. This type of middle housing is meant for first-time buyers, the mayor said.

"So by providing greater incentives for maintaining existing housing and by legalizing different kinds of housing, we are doing everything we can from a policy perspective to avoid unnecessary tear downs."

Accountability

The legislation doesn't feature any requirements that would hold landlords accountable for using quality materials or requiring continued upkeep. These are issues the city are fighting against in lawsuits with out-of-town investors such as Texas-based VineBrook Homes. It's these problems residents are concerned about, particularly West Siders, and are seeking to have addressed before they happen.

The mayor has answer for this, too. He wants more development there so the market can grow.

The city further addresses this concern − along with questions about overwhelmed infrastructure − in a new comprehensive FAQ available on the Connected Communities website.

And one last thing...

At the very end of the ordinance (yes, we read it), there are multiple small provisions including making outdoor dining permits more accessible, allowing daycares to be built in single-family areas, and enforcing leash laws.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: What is Cincinnati's Connected Communities zoning plan?