Conn. River dam licensing offers chance for change

MONTPELIER, Vt. (AP) — Five big hydroelectric projects on the Connecticut River are up for federal relicensing, providing a once-in-a-generation chance for environmentalists, recreational river users and others to recommend changes to the dams' operations.

The projects affect a roughly 85-mile stretch of the river, which forms the boundary between Vermont and New Hampshire, bisects Massachusetts and Connecticut and then flows into Long Island Sound.

"It's a huge opportunity for the public and project operators to think about not just one location but a whole stretch of river," said Andrew Fisk, executive director of the Connecticut River Watershed Council, based in Greenfield, Mass.

Site visits set for the first week of October will kick off a process of environmental reviews and public meetings that's expected to take five to six years.

It's too early to know what issues will garner the most attention during relicensing, environmental group leaders and dam owners TransCanada Corp. and FirstLight Power Resources of Glastonbury, Conn., said last week.

The dams provide low-cost power without big carbon emissions, as well as jobs and big tax revenues in nearby communities, spokesmen Grady Semmens of TransCanada and Charles Burnham of FirstLight said.

Fisk said one area of study may be the impact that raising and lowering river levels behind the dams has on fish and wildlife species, particularly at Wilder. A second issue may be whether enough water is being left in the river to support fish populations below the Turners Falls dam.

Relicensing begins less than three months after the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced it was abandoning a nearly half-century effort to restore populations of Atlantic salmon that had dwindled in the Connecticut basin after the dams were built, saying the program had not been successful enough to justify the continuing cost.

The dams' need for new licenses was not part of the decision to discontinue the salmon restoration program, said Bill Archambault, regional assistant director for fisheries with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. "Our decision was really based on the science and where we were (with) the program," he said.

Salmon are born in inland streams, and migrate to the ocean before returning to the rivers to reproduce. Salmon were so plentiful in the Connecticut when Europeans arrived in New England four centuries ago that indentured servants had provisions written into their contracts limiting the amount of times per week they could be fed it.

New fish ladders and passageways were built in recent decades to try to get the salmon around the dams, but those efforts proved unsuccessful. Fisk said, though, that a bigger problem has been heavy fishing for salmon in the Atlantic. Fish stocked in the Connecticut and its tributaries have made it to the ocean but have not returned.

As the process unfolds, Fisk said his group will be looking for members of the public to be voicing any concerns, including calls for better environmental stewardship or recreational opportunities.

"It's your river. You've given a private entity a very legitimate right to operate on it, but the public needs to get something in return for that," he said.

They five projects include three hydroelectric stations owned by TransCanada on the river between New Hampshire and Vermont and two in Massachusetts, owned by FirstLight. From north to south they are:

— The 41-megawatt Wilder station, which dams the river between the Wilder section of Hartford, Vt., and Lebanon, N.H.;

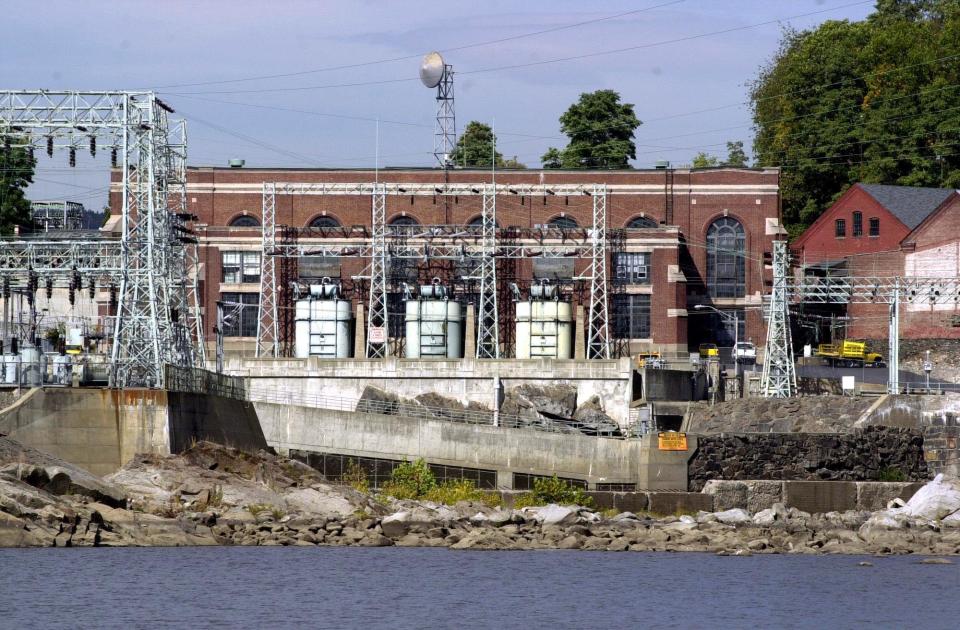

— The 49-megawatt Bellows Falls station between the village of Bellows Falls in Rockingham, Vt., and Walpole, N.H.;

— The 37-megawatt Vernon station, between Vernon, Vt., and Hinsdale, N.H.

— The Northfield Mountain Pump Storage Facility, in Northfield, Mass., a 1,119-megawatt station where water is pumped from the river to an uphill reservoir during times when power demand is low and then released to generate power as it flows downhill when demand for electricity is high;

— The 68-megawatt Turners Falls station in the Turners Falls section of Montague, Mass.