Congress readies itself for start of Trump impeachment trial

Capitol Hill is headed for a week of anticlimactic limbo this week, as Congress jumps through a number of procedural hoops required to actually begin a Senate impeachment trial.

The House is expected to vote Wednesday to send articles of impeachment to the Senate and name managers who will prosecute the case against the president, ending a nearly monthlong delay by House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif.

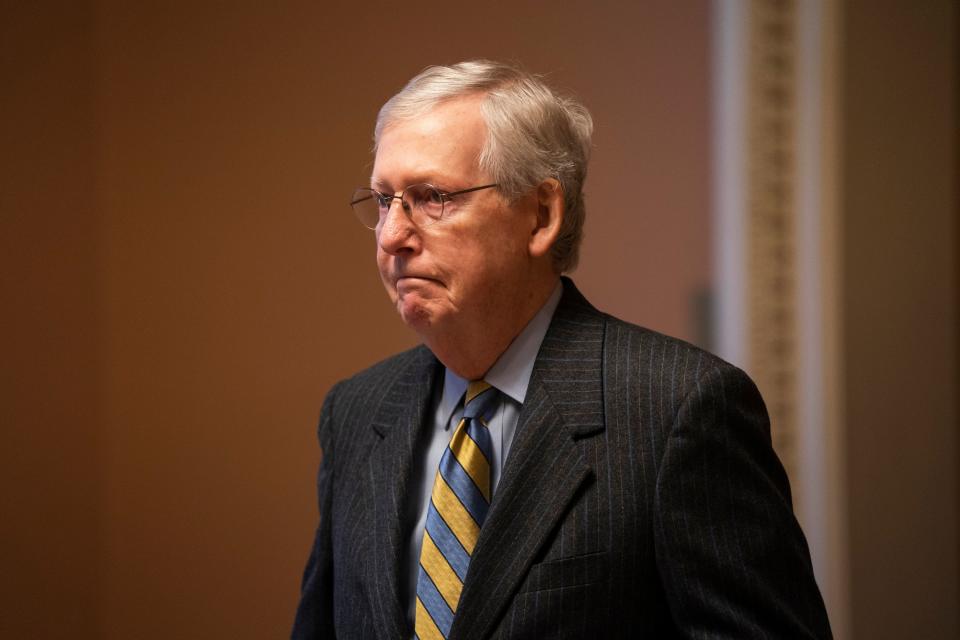

But the Senate won’t begin its trial for almost a week after that. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., told reporters Tuesday afternoon that the trial won’t start in earnest until next Tuesday, after some “preliminary steps” this week.

It’s virtually certain that the trial will impact the Democratic presidential primary, lasting past the Feb. 3 Iowa caucuses. The bigger question now is how much the trial might interfere with the Feb. 11 New Hampshire primary.

So what happens between now and next week?

There are a few steps the Senate has to take before the trial begins, as outlined in Senate rules for an impeachment trial that were written in 1986. These rules were used as a template in the 1999 Senate impeachment trial of then-President Bill Clinton, with some changes. The current Senate will rely on the 1986 rules and Clinton trial precedent while also making some changes of its own.

First, the House managers need to present the articles of impeachment to the Senate. When they enter chamber, the sergeant at arms will be instructed to proclaim, “All persons are commanded to keep silence, on pain of imprisonment, while the House of Representatives is exhibiting to the Senate the United States articles of impeachment against President Donald John Trump.”

The leading House manager, possibly someone like House Intelligence Chairman Adam Schiff, D-Calif., would then read the text of the articles in the chamber.

Second, the Senate needs to be organized and prepared for the trial. In 1999, that meant the Senate had to pass a measure to suspend the rule forbidding photographs in the Senate chamber, to allow for one photograph the day senators were sworn in to begin the trial. (Another measure was passed unanimously to allow for photographs to be taken the day the Senate voted on Clinton’s guilt.)

A separate measure was passed to provide for “the installation of appropriate equipment and furniture in the Senate chamber.” That measure provided for a lectern for House managers, a table and chair for witnesses and a table and chairs for House managers, as well as the addition of video screens.

Third, the Senate must pass a measure issuing a summons “to the person impeached … notifying him to appear before the Senate upon a day and at a place to be fixed by the Senate.”

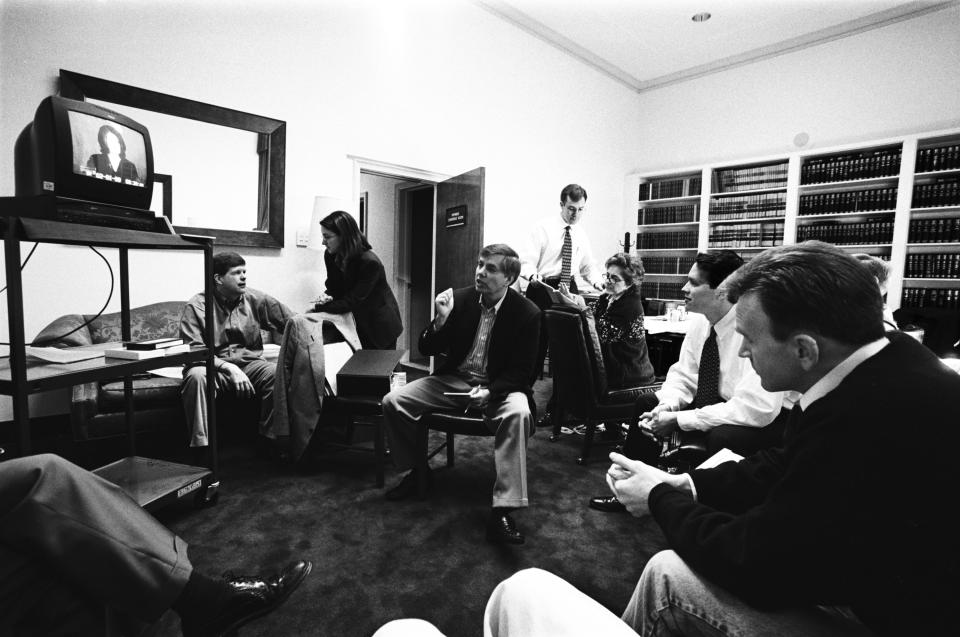

In 1999, the process of adopting the new measures took a week. On Wednesday, Jan. 6, 1999, the House appointed managers and sent the articles to the Senate. It’s an eerie similarity to the present, with Pelosi set to hold a House vote on a Wednesday to do the same thing.

On the morning of Thursday, Jan. 7, 1999, the 13 House managers walked into the Senate chamber, and Rep. Henry J. Hyde, R-Ill. — then chairman of the House Judiciary Committee — read the articles aloud. After doing so, the House members departed. In the afternoon, then-Chief Justice William Rehnquist was sworn in. He, in turn, swore in the senators.

At that point, the Senate had not yet agreed on rules to govern the trial. That’s not the case now. McConnell, the Senate majority leader, plans to pass a set of rules relying solely on the 53 Republicans in the chamber. On Friday, Jan. 8, 1999, all 100 senators met in the old Senate chamber, down the hall from the current chamber on the second floor of the U.S. Capitol. They reached unanimous agreement there on a set of rules that postponed the contentious question — that once again faces the Senate — about whether to call witnesses.

That was technically the beginning of the trial, with the Senate adopting what is known as an “organizing resolution” to put the rules for the trial in writing. But opening arguments didn’t take place until the following Thursday, Jan. 14. That’s when the Senate did the fourth thing it must do: suspend its regular business and finally begin its trial.

McConnell said Tuesday that he didn’t expect to reveal the text of the organizing resolution for this trial until next Tuesday. There may be a short break after this to allow for both sides to file legal briefs laying out their arguments, which was the reason for the delay in 1999 between Jan. 8 and Jan. 14.

The Senate didn’t decide the question of witnesses in 1999 until Jan. 28 and allowed for three witnesses to testify via videotaped depositions. It also voted on a motion to dismiss the trial then, which failed. Only 44 senators voted to dismiss, against 56 who voted against dismissal. It was a party-line vote, with all Republicans voting against dismissal and all Democrats except one — Sen. Russell Feingold of Wisconsin — voting in favor.

The Clinton impeachment trial lasted five weeks and ended on Feb. 12, 1999, with an acquittal on both counts. A supermajority of senators (67 if all 100 members are present) is required to convict. On the question of perjury, the vote was 55 for acquittal — all the Democrats and 10 Republicans clearing Clinton — and 45 for conviction. On the charge of obstruction of justice, all 45 Democrats and five Republicans voted for acquittal, while 50 senators voted for conviction.

Today’s battle over witnesses is a mirror image of 1999. Then, Republicans were driving impeachment of a Democratic president, and they were pushing hard for the inclusion of witnesses in the Senate trial.

“I have never seen a trial before where you had factual disputes where you didn't have witnesses where you could watch their demeanor on the stand, listen to them, judge one witness versus another witness. That’s basically our system of justice,” said then-Sen. Mike DeWine, R-Ohio, who is now Ohio’s governor.

Now, Republicans are defending a president from their own party, and McConnell is making arguments that sound like a case against new witnesses at the least, and possibly any and all witness testimony.

“If the existing case is strong, there’s no need for the judge and the jury to reopen the investigation. If the existing case is weak, House Democrats should not have impeached in the first place,” McConnell said Tuesday on the Senate floor.

In 1999, Democrats were defending the president and said witnesses were not needed in the trial.

“We have a body of evidence that is really phenomenal … that I think probably answers virtually every scintilla of question there would be about what happened and why it happened. We know the facts,” then-Senate Minority Leader Tom Daschle, D-S.D., said.

Now, Democrats say witnesses are vital.

“Do Senate Republicans want to break the lengthy historical precedent … by conducting the first impeachment trial of a president in history — in history, since 1789 — with no witnesses? … That seems to be where the Republican leader wants us to be headed,” Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., said Tuesday.

So in some ways it’s all just a partisan exercise. But there are substantive differences that Democrats say make their arguments legitimate both in 1999 and now.

In 1999, Democrats say, independent counsel Kenneth Starr had conducted a lengthy investigation into Clinton and had spoken with all relevant witnesses and also had possession of nearly all the documentary evidence he sought, “60,000 pages, five volumes — an amazing array of data,” as Daschle put it. And there was bipartisan concern that the salaciousness of testimony by Monica Lewinsky would lower the dignity of the Senate.

Now, Democrats say, the president has blocked key witnesses from testifying and withheld vast amounts of documentation subpoenaed by the House. The Senate should press the issue simply as a matter of upholding the separation of powers, they say.

McConnell and Republicans fire back that the House could have waited to let its dispute with the Trump administration over witnesses and documents play out in the courts.

“There’s a reason why the Clinton impeachment inquiry drew on years of prior investigation and mountains of testimony from firsthand fact witnesses,” McConnell said Tuesday. Republicans in 1999, he said, “knew they had to prove their case before submitting it to the Senate for judgment.

“Nothing, nothing in our history or our Constitution says a House majority can pass what amounts to a half-baked censure resolution and then insist that the Senate fill in the blanks,” McConnell added. “There’s no constitutional exception for a House majority with a short attention span.”

But it appears McConnell has his work cut out for him on this matter, because there are a handful of Republican senators who have signaled they want to hear from former national security adviser John Bolton at the least. He is one of four current or former Trump administration officials who Schumer has requested as witnesses. The others are Mick Mulvaney, acting White House chief of staff; Michael Duffey, Office of Management and Budget associate director for national security; and Robert Blair, senior adviser to the acting White House chief of staff.

For the next few days, until the trial’s arguments actually begin, this fight will fill up much of the debate in Washington: How is the current moment similar to 1999, how is it different and how does that dictate whether witnesses should testify, and if so, which ones?

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Did the U.S. 'assassinate' Iranian general or just kill him? Why it matters

Saudis warn of new destructive cyberattack that experts tie to Iran

Your Democratic primary cheat sheet: In the run-up to Iowa, who's still in the race?

PHOTOS: Ukraine International Airlines plane crashes in Iran killing all on board