Congress fights back against the imperial presidency

WASHINGTON — For at least two decades, sitting presidents have challenged what millions of Americans learned in social studies class: that the three branches of government are coequal, and that while each branch has different powers, no branch is more powerful than any other. That is no longer the case because the White House has grown in stature so that it now towers over both Congress and the courts.

The imperial presidency has been a bipartisan project, enthusiastically taken up by George W. Bush but continued by Barack Obama and, most recently, Donald Trump. All three have waged war abroad with only meager congressional authority. All three have also resisted efforts by Congress to exercise oversight over domestic affairs.

In recent weeks, however, there have been signs — admittedly nascent — that the imperial presidency faces more intense resistance than it has in years and that Congress is intent on reclaiming some of the power it has ceded to the White House. The judiciary is fighting back too, helping Congress reassert its power.

The anti-imperial push is reflected in a ruling by District of Columbia District Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson, who recently held that the White House could not grant senior officials “absolute immunity” from honoring a congressional subpoena related to the investigation into Russian electoral interference.

“Presidents are not kings,” Jackson wrote in an opinion that resounded with the Founding Fathers’ own anxieties about the limits of executive power.

Some of this constitutional pull-and-tug is a function of politics, with Democrats in the House of Representatives determined to check the president at every turn. Much as they might care about checks and balances, their main goal is to get rid of Trump.

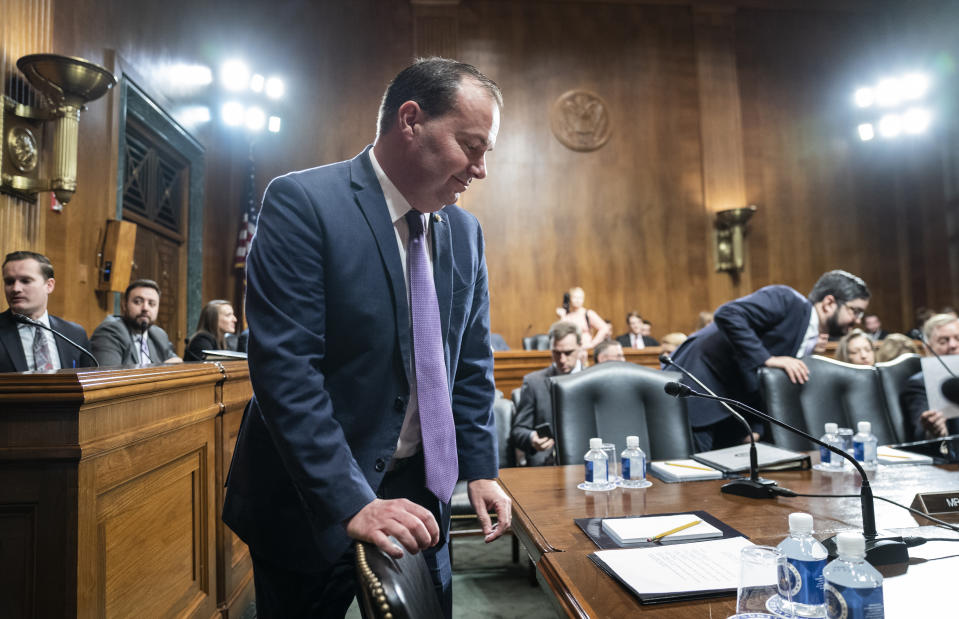

Party politics, however, cannot account for Republican Sen. Mike Lee of Utah fuming about the Trump administration's inadequate explanation for the airstrike that killed an Iranian general in Iraq. Or a handful of House Republicans voting with House Democrats in endorsing a war powers resolution that would severely curtail Trump's ability to unilaterally engage in a military conflict with Iran. Ineffectual as they might turn out to be, these are nevertheless the rumblings of principle.

And while impeachment has been a starkly partisan affair, here too Congress has fought to maintain its prerogatives. Even as Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell seeks a quick trial that will exonerate Trump, reports came on Friday that Susan Collins, R-Maine, was, according to the Bangor Daily News, “working with a ‘fairly small group’ of fellow Republican senators” to ensure that the trial will include witnesses, a demand by Democrats that Republican leaders have resisted. By Monday, it was widely reported that at least three Republicans would side with Collins. If so, they and the chamber’s 47 Democrats would constitute a majority that would likely frustrate Trump’s desire to have the trial move along as briskly as an episode of “Night Court.”

Even some of the president’s closest supporters have grown skittish, perhaps aware that any power he accrues he will likely leave to a Democratic successor. Writing in the conservative Washington Times, former judge and Fox News mainstay Andrew Napolitano warned of the “dangers of a Trump imperial presidency.” That one of the president’s formerly closest supporters would sound such a warning amounted to a warning of its own.

And then there was Tucker Carlson, the primetime Fox News host who acts as an informal presidential adviser, thundering against the attack on Iranian Gen. Qassem Soleimani in a striking departure from the boosterism of colleagues like Sean Hannity. “Our leaders should explain to us how that conflict will make the United States richer and more secure,” Carlson said last week. “There are an awful lot of bad people in this world; we can’t kill them all. It’s not our job.”

The imperial presidency is an informal term — coined by the historian Arthur Schlesinger — to describe the insistent accumulation of power in the executive branch, and the Oval Office in particular. Power is finite and must come from somewhere. Throughout U.S. history, the growing power of the president has been paralleled by the waning power of Congress.

That has been especially true in times of war, when it is easiest for presidents to claim they are taking unilateral action for the sake of national security. Some date the birth of the imperial presidency to the Civil War, when Abraham Lincoln suspended the writ of habeas corpus, thus violating one of the sacrosanct principles of American government. “Lincoln the Dictator,” a 2010 scholarly article called him.

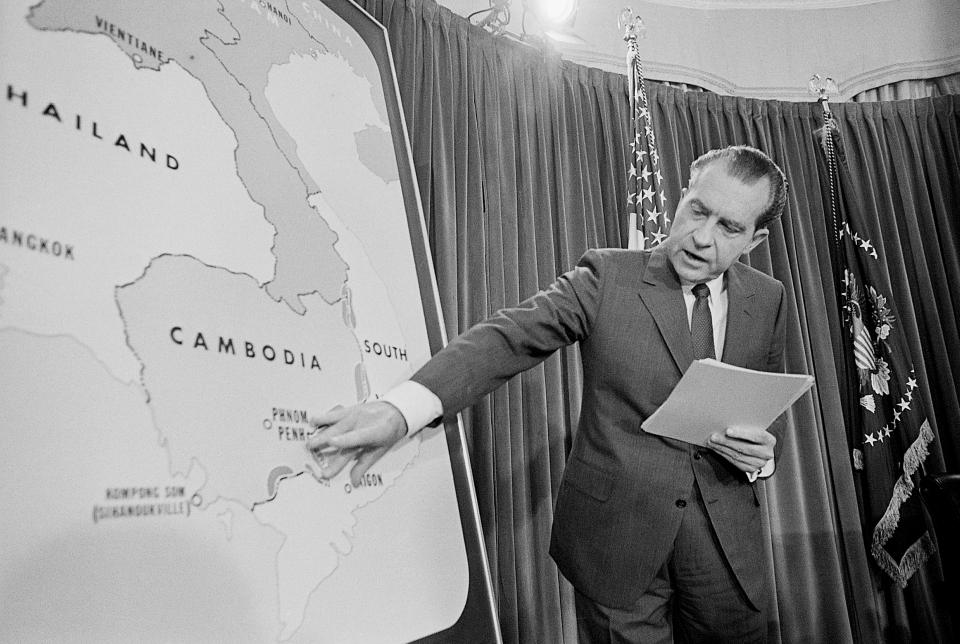

Richard Nixon is the most notorious imperialist in American history. Without any authority from Congress, he initiated the secret bombing of Cambodia. Displeased by $8.7 billion that Congress appropriated for various domestic programs, Nixon simply impounded the money so that it could not be spent.

After leaving office, Nixon offered a defense that could also serve as a justification for any number of presidential actions, from Obama’s drone warfare in the Middle East to Trump’s emergency declaration to build a border barrier in Mexico: “Well, when the president does it,” Nixon mused, “that means it is not illegal.”

Watergate was enough of a scare for Congress to reassert its power in the years following Nixon’s resignation. That rebalancing culminated in the impeachment of Bill Clinton in 1998. “The End of the Imperial Presidency,” said the headline of a New York Times op-ed by presidential historian Michael Beschloss, published just as Clinton was preparing to leave office.

Nine months later, airplanes hijacked by terrorists crashed into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Three days after that, the House voted 420 to 1 to pass the Authorization for Use of Military Force, or AUMF, which effectively gave the president power to fight terrorism wherever and however he saw fit, without seeking additional congressional approval.

A lone legislator, Rep. Barbara Lee of California, voted against the measure. While some criticized her for an alleged lack of patriotism, her dissent has come to be seen as a prescient stand against unchecked power. In a vindication of Lee’s original vote, last year the House voted 226 to 203 to “sunset” the AUMF.

That second vote was as much a rebuke of Obama as of Trump. Despite winning the Nobel Peace Prize early in his first term, Obama used his AUMF authority to launch 563 drone strikes in Africa and the greater Middle East, according to the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of civilians.

And he continued with Bush-era practices like warrantless detention of terrorism suspects. “This isn’t exactly change we can believe in,” grumbled legal adviser Harold Koh, quoted in “Kill or Capture,” a book about Obama’s tortured national security strategy by Yahoo News Editor in Chief Daniel Klaidman.

Obama also engaged in imperial behavior on the domestic front. For example, his administration refused to turn over White House visitor logs. When it finally did so, in the face of a legal challenge, those logs were heavily redacted.

With his agenda largely stymied by Congress, Obama signed momentous — and controversial — executive orders providing a path to citizenship for some children of undocumented immigrants, known as Dreamers, establishing more strict gun control measures and preparing the American economy to transition to an all-renewable energy portfolio.

Like every other Republican nominee, Trump promised to end Obama’s rule-by-decree. “I don't like executive orders,” he said shortly after declaring for the presidency in 2015. “That is not what the country was based on. You go, you can’t make a deal with anybody, so you sign an executive order.”

Since taking office, however, Trump has signed 137 executive orders, issuing them at a faster rate than Obama.

The executive orders are a relatively minor issue for the Democrats who have wanted to remove Trump from office ever since they retook the House in the 2018 midterm elections. Trump has branded their efforts — whether over the Russia investigation or the Ukraine pressure campaign — a politicized “witch hunt.”

At the same time, Trump has made things harder for himself by utterly refusing to comply with any of the Democrats’ investigations into his administration. He has claimed that Article II of the Constitution affords him “the right to do whatever I want as president.” Such hubris has inadvertently bolstered the Democrats’ case, allowing them to argue that as much as they are worried about Trump, they are even more worried about the imperial presidency he has come to epitomize.

“What President Trump is trying to do is a huge step toward an imperial presidency,” the Republican strategist Matthew Dowd counseled on Twitter last year. “Time for Congress to recapture authority.”

Congress has tried. Its most visible effort has been the impeachment inquiry, with the House endorsing two articles of impeachment against Trump. “He has laid siege to the foundation of our democracy,” said Rep. Mike Quigley, D-Ill., as he prepared to vote for both articles.

And in two lawsuits now moving through District of Columbia circuit court, House Democrats are challenging Trump on his refusal to comply with any oversight of his administration. One lawsuit demands that former White House counsel Don McGahn testify before Congress; the second seeks grand jury testimony from Robert Mueller’s probe into Russian electoral interference.

Realistically, Democrats know that neither lawsuit is likely to be resolved in time for them to take meaningful action against Trump in his first term, but a Supreme Court decision in either could actually prove more consequential than the outcome of a Senate impeachment trial, which is all but certain to culminate in an acquittal by the Republican-controlled chamber.

That’s because the lawsuits strike at the heart of the imperial presidency. Arguments by administration lawyers have brought that point into stark relief. At a recent hearing, Justice Department attorneys maintained that Congress essentially has no authority at all to oversee the White House. That assertion seemed to stun the judges. “Is there no proper role for the courts?” one of them wondered.

Reasserting that authority is arguably more important than catching Trump in a lie about Ukraine, especially since no amount of Democratic fact finding seems likely to lead to his removal from office.

The killing of Soleimani came in the midst of the Ukraine impeachment inquiry and seemed only to exacerbate concerns about Trump’s refusal to allow for any executive accountability. Members of Congress had no prior notice of the planned strike; nor did the briefing they received after the fact allay concerns.

If anything, it made things worse. “That was insulting,” complained Sen. Mike Lee of Utah. “That was demeaning to the process ordained by the Constitution. And I find it completely unacceptable.” Lee quickly offered assurances that he remained an ardent Trump supporter. Yet he did not retract his rebuke.

Another rebuke came when the House passed a resolution, predicated on the War Powers Act of 1973, that would hamper Trump’s ability to conduct an expanded military campaign against Iran, which was considered a real possibility just last week but has not yet materialized. Whereas no House Republicans broke ranks on the impeachment vote, this time three of them voted with Democrats to restrain the president’s authority to wage war. And at least four GOP members are expected to vote for the resolution once it makes its way to the Senate floor.

Among the House dissenters was Matt Gaetz of Florida, who is among the president’s most ardent supporters on Capitol Hill. “Reclaiming Congressional power is the constitutional conservative position!” a staffer for Gaetz wrote in an email to other Republican legislators.

A displeased White House urged Gaetz to “reconsider his points of view.” He declined to do so.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Did the U.S. 'assassinate' Iranian general or just kill him? Why it matters

Saudis warn of new destructive cyberattack that experts tie to Iran

Your Democratic primary cheat sheet: In the run-up to Iowa, who's still in the race?

PHOTOS: Ukraine International Airlines plane crashes in Iran killing all on board