“A New Concept of Nationalism Needed for Iran”

Is it more nationalist to become a martyr or to create jobs for the country?

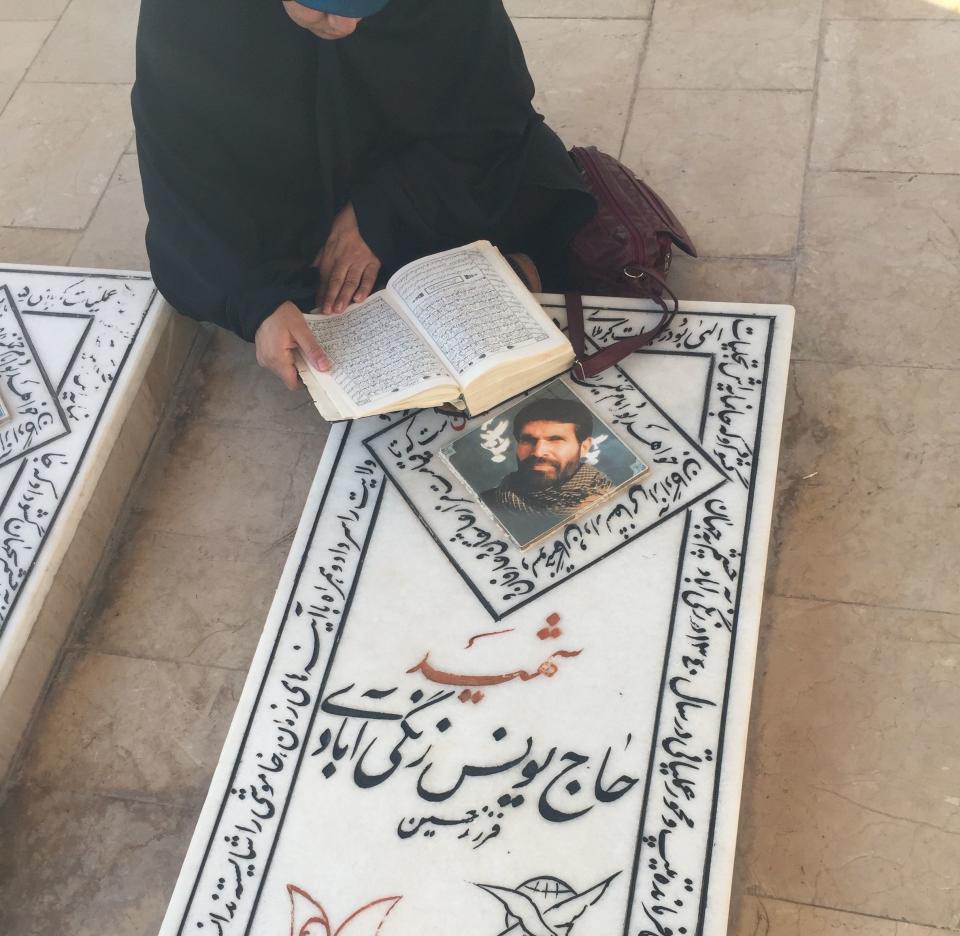

I was walking through a graveyard reading the names of the martyrs that were laid to rest. Suddenly, I saw my full name carved on a tombstone with a religious woman whispering prayers and reading the Quran.

I told her (in picture) that my name is also Younes Zangiabadi. She smiled while being extremely surprised and said: so there is another Younes Zangiabadi in this world. She proudly continued: my husband, Younes was a true nationalist:

“He gave up his dreams, family and life to serve this country. Despite Saddam’s unlimited support of the West, my husband, and many other martyrs single-handedly stood against them all and fought for the people so that now we can all live safely in Iran.”

As I was lost in my thoughts trying to picture her husband’s character, she suddenly asked: so, now you are Younes Zangiabadi, what will you do for the country, young man?

I wanted to show her that I am a nationalist too, but I couldn’t think of a way to prove it. First, I live in the West, the adversary to whom her husband lost his life fighting. Second, her generation’s concept of nationalism did not align with mine and I couldn’t help but wonder whether I was less Iranian than Younes was?

Since the victory of the Islamic Revolution in 1979 and the Iran-Iraq war in 1980, the establishment (Nezam) has repeatedly advertised and promoted the culture of Martyrdom (Shahadat) as the highest level of nationalism that a citizen can possibly aspire to become.

In Iran, martyrs and their family members receive exclusive privileges and social status. Their stories and lifestyles get great coverage on national media, their Memoriam are constantly posted all over the country, and main highways, streets, schools and hospitals are often named after them.

Despite this vigorous top-down approach to advertisement, young Iranians like myself do not really associate ourselves with the concept of martyrdom as we were neither part of the revolution nor the Iran-Iraq war. This state propelled propaganda has even reduced the usual level of respect for soldiers amongst the majority of the youth in Iran.

Now, more than ever, young generations need to appreciate Iranian security and military forces for providing safety and stability in the country. Iran is at the forefront of the fight against ISIL in Syria and Iraq, but there has not yet been a single successful terrorist attack in the country. Top officials claim that this stability is a pure product of Iran’s involvement in the region where young Iranians voluntarily risk their lives to prevent terrorism from infiltrating its way through Iran’s border.

The establishment is now using this new war in Syria to revive the forgotten culture of martyrdom amongst the youth. As a result, we should not be surprised that young soldiers that are being sent to Syria and Iraq are now publicly advertised as devoted Iranian nationals and martyrs once again.

Many young Iranians, like Younes, have sacrificed their lives for this country, I don’t know what I could do for Iran but I understand my country has long passed the era of revolution and martyrdom. In contrary to our parent’s generation who were revolutionary and anti-Western, my generation is no longer stuck with these ideologies.

We want a respectful and constructive relationship with the international community, a healthier and prosperous economy, and more civil liberties. But unlike the revolutionary generation, we simply do not have the same sense of nationalism and political will to collectively push for them.

Nowadays, materialism and individualism have become fundamental parts of youth culture and this should not be an unexpected phenomenon. In a society where human values are mainly based on your home address, car, and fashion, young people have no other options but to lean toward materialism and individualism to express their identity.

Systematic corruption and nepotism play a key role in consolidating this new culture. Young people understand that it is always the people with a connection to the establishment who own luxurious mansions, cars, and lifestyles.

In recent years, social media has also been a catalyst in promoting this materialistic culture, like Instagram pages such as “Rich Kids of Tehran”, capturing the essence of this culture and gaining popularity among thousands of young people.

In this materialist and financially-divided society, achieving financial security is the only way for the young generation to survive and progress. As the road to financial security is quite long and bumpy with an ordinary career, many young people would rather get involved in corrupt and illegal activities to traverse this path in a shorter period of time, just like the people at the top.

I see this new culture as a byproduct of a systematic martyrdom culture that has been propagated to young people for the past 37 years. I believe both cultures are extreme in their own ways.

Iran needs a new concept of nationalism that combines both generation’s ideologies. The combination that possess the nationalist and politically concerned character of the revolutionary generation as well as the optimist and liberal perspectives of the young generation.

This new concept will create a balanced society where martyrs are greatly appreciated for their service. A society where being a martyr doesn’t necessarily make you more nationalist than someone who creates jobs. Indeed, Iran is in a state that needs its young people to be employed as opposed to being sent to war.

With more than 60 percent of the population under the age of 30, the government must use this generation as an influential force to push for gradual changes to a more socio-economic based culture where creating jobs are promoted, not a martyrdom culture.