Community ordinances are clashing with Michigan’s drug harm reduction strategy

When it comes to trying to reduce the devastation that accompanies the use of illicit drugs, experts say Michigan is working against itself.

Here's what's happening: In an effort to keep people alive, the state of Michigan is funneling millions of dollars from settlements with opioid manufacturers and distributors into a strategy called harm reduction — reducing the harms associated with drug use. That means easy access to Narcan, which can reverse an opioid overdose if given quickly and correctly. It also means reducing the spread of infectious disease by providing clean syringes to intravenous drug users. And it means providing kits to test drugs for the presence of ultra-deadly fentanyl in street drugs.

At the same time, hundreds of local communities have paraphernalia ordinances that prohibit people from possessing or providing syringes and other supplies, including kits to test for the presence of fentanyl in street drugs. What's legal in one community may be illegal in another.

Harm reduction advocates say the local laws are compromising their efforts and punishing drug users who are trying to do what health officials advise.

"We're basically criminalizing people trying to protect their health and protect the community's health," said Steve Alsum, executive director of the Grand Rapids Red Project, a prominent harm reduction agency in west Michigan that supplies syringes and test kits. Syringe services programs "could provide more benefit to more of the community if these programs were legal state wide."

So what does this clash of laws and philosophies really mean?

And why does it matter to people who don't use drugs?

Back up, drug users can get free needles?

They can — and they can get more than that.

A variety of syringe service programs across the state, including ACCESS in Sterling Heights, the Red Project, and Harm Reduction Michigan in northern Michigan and the Families Against Narcotics' Harm:Less mobile unit, use opioid settlement money to supply needles and other harm reduction equipment to drug users.

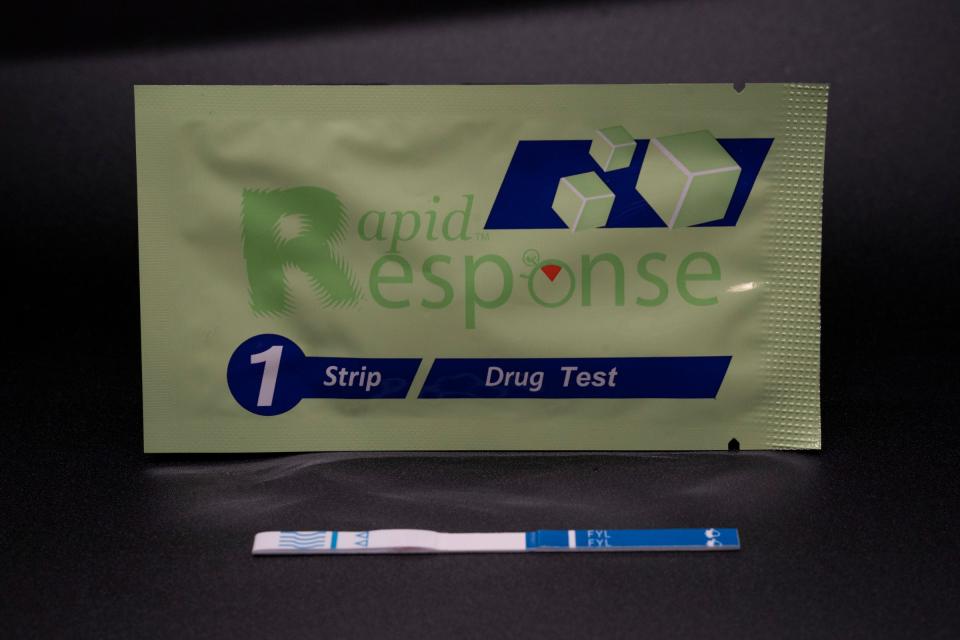

Among those supplies: Kits to determine whether drugs contain fentanyl, the synthetic opioid that is involved in the majority of the nation's 100,000-plus overdose deaths a year, including roughly 3,000 in Michigan.

And, kits to test drugs for xylazine, a potent, non-opioid large animal tranquilizer that is most often mixed into fentanyl. Last year, Oakland County Sheriff Michael Bouchard said xylazine was present in up to 85% of the fentanyl his department seized. Because it is not an opioid, xylazine is impervious to Narcan.

To find a complete list of syringe service programs, go to rb.gy/osre70

Relapse. Overdose. Saving lives: How a Detroit addict and mom of 3 is finding her purpose

How many needles are we talking about here?

We're talking about more and more syringes every year.

In the fourth quarter of 2023, syringe service programs across the state distributed nearly 1.2 million syringes, a 30% increase compared with the fourth quarter of 2022, accoridng to data from the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS).

So these syringe service programs help addicts do drugs?

They recognize the reality of drug addiction, advocates say.

Addicts are going to use whether or not they have access to clean needles; that's the nature of addiction. Shared needles promote the spread of HIV and Hepatitis C. Reusing needles promotes endocarditis, an infection that inflames the lining of the heart's valves and chambers.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, people who participate in a syringe service program lower their risk of contracting HIV or Hepatitis C by 50%.

“Most people who inject drugs, if they have access to sterile, unusued syringes, they're going to use a sterile, unused syringe each and every time they inject," said Alsum. "The reason people share or reuse syringes is there's a lack of access to them caused by the criminalization of that tool."

In addition, research shows people who participate in syringe service programs are five times more likely to seek treatment for their addiciton than are those who do not participate in needle exchange programs.

And because fentanyl and xylazine have infiltrated street drugs, providing kits to test for the presence of those substances, can save lives. They may still use their fentanyl or xylazine-laced drugs, but they may choose to use at a slower pace or choose to use in the presence of someone who can call for help if they overdose.

Not everyone agrees with this approach. Opponents argue that passing out clean needles only enables drug use. Opponents also argue that there's a reason paraphernalia laws are on the books: drugs are dangerous and a menace to society.

A change of leadership in the Eastpointe Police Department shut down the Harm:Less syringe service mobile unit late last year. It had been operating at the intersection of Eight Mile and Gratiot for some time.

Eastpointe Police Chief Corey Haines directed Free Press questions about the decision to City Council.

"We are relying upon the in depth expertise of our Chief of Police to ensure that the health, welfare and safety of our residents, businesses and visitors are prioritized," said Assistant City Manager Kim Homan. "Properties at the Gratiot and 8 Mile Road's intersection reflect an important entrance to our city."

What's so difficult about obeying the law?

When it comes to syringes and other drug paraphernalia, laws aren't consistent.

"Every city has this patchwork of ordinances," said Andrew Coleman, who runs harm reduction programs for ACCESS (the Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services), which has offices in Sterling Heights and Dearborn.

Sterling Heights, for example, allows syringes and parapheranalia for illicit drug use as long as they are distributed by a recognized health authority with the aim of stopping the spread of innfectious disease. As a result, ACCESS is able to give out syringes in that community.

But Dearborn outlaws the posession and use of all syringes and paraphernalia related to illicit drugs ― even if they come from a legitimate harm reduction agency, which mean ACCESS is not allowed to provide syringes in that city.

Lincoln Park, which has one of the highest rates of drug overdose deaths in the state, also outlaws them. It also considers products designed to test drugs, such as fentanyl test strips, as paraphernalia.

In Flint, which also has one of the highest overdose death rates in the state, it's illegal to give away, furnish or display hypodermic needles or any other device designed or adapted for drug use, although those rules do not apply to participants of the Wellness AIDS Service Incorporated Approved Syringe Exchange Program.

In Detroit, paraphernalia, including syringes and test strips, are illegal unless provided by an authorized syringe exchange program.

So what's legal in one community isn't necessarily legal in another.

The state has a law, too: Selling syringes is illegal, unless they're sold by an agency authorized to reduce the transmission of infectious disease; except those agencies don't sell syringes, they give them away.

“It seems kind of crazy to have really begun to encourage these programs but not have that issue taken care of," said Pam Lynch, director of Harm Reduction Michigan, which is based in Traverse City and Petoskey, but does work throughout the state.

For fiscal year 2024, the state allocated $4.2 million of opioid settlement money for syringe service programs, according to MDHHS.

Why can't people just drive to where paraphernalia is legal and get it there?

They can. But posessing syringes or driving with them in communities where they are not legal can still result in criminal charges.

In most cases the maximum punishment is a $500 fine and/or 90 days in jail.

But for someone who is already on probation, an additional charge can mean a probation violation, which can result in more sanctions.

In addition, harm reduction workers who distribute the syringes or other outlawed paraphernalia could be charged with possessing or supplying contraband.

And Lynch pointed to another issue:

Syringe service programs also dispose of used syringes. Used syringes contain residue or small amounts of illicit drugs and having one of those could lead to a drug posession charge.

As a result, Lynch said, drug users "are disincentivized to return used syringes … they're disincentivized to take those public health measures. … By people not being able to use sterile equipment to prevent disease and return it safely, (the state is) kind of working against itself."

I don't do drugs, why should care about this?

There's the humanitarian aspect.

But there's also the financial aspect.

"The longer term, the bigger picture outcomes of paraphernalia ordinances are increased services at emergency departments, increased services for HIV," said Lynch.

From 2002-2012, U.S. hospitalizations for drug-related infections cost more than $700 million a year, according to research cited by the CDC. And that was before, the opioid epidemic and the intravenous drug use that it fostered reached fever pitch.

The most common payer for those hospitalizations: Medicaid, which is partly funded by state taxpayers.

Meanwhile, in 2017, opiod addiction alone cost the United States $1 trillion in health care, treatment, incarceration, lost productivity and reduced quality of life, according to the CDC.

Will the state make its rules constistent across Michigan?

Last year, state Rep. Carrie Rheingans, D-Ann Arbor, introduced a pair of bills that, if passed by Lansing lawmakers and signed by Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, would alleviate the concerns of harm reduction advocates.

House Bill 5178 would decriminalize the posession or distribution of needles, hypodermic syringes or drug paraphernalia aimed at reducing the spread of infectious disease by who those who work at legitimate syringe exchange programs and for those who participate in them. The bill would also decriminalize controlled substance contained in a used needle, hypodermic or drug paraphernalia if the amount of the substance is an amount sufficient only for personal use. The rules set forth in the bill would supercede all local ordinances.

House Bill 5179 would legalize products used to determine whether a controlled substance includes adulturants, including but not limited to fentanyl kits.

Rheingans, who holds dual master's degrees in public health and social work, had previously worked in HIV outreach and needle exchange.

“People in the general public and my colleagues look at it as a way to let people keep using and injecting drugs." she said. "People don’t understand that it’s a good public health measure.”

Contact Georgea Kovanis: gkovanis@freepress.com.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Community ordinances clash with Michigan drug harm reduction strategy