Common misunderstandings about Miranda warnings

The Miranda warning comes from one of the biggest legal cases of the 1960s–and thanks to countless arrest scenes in TV and movies, it’s one of the best-known applications of the Fifth Amendment. But what you don’t know about Miranda could be more significant than you think.

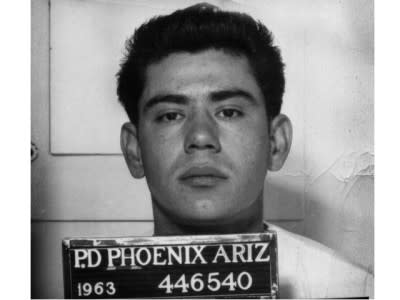

Ernesto Miranda arrest photo, 1963.

Last year, there was a big debate about the Miranda warning and Boston terror suspect Dzhokhar Tsarnaev. Federal investigators said after Tsarnaev’s detention that he wouldn’t be read his Miranda rights under something called the “public safety exemption.”

Under the exemption, police can interrogate a suspect without advising him or her of Miranda rights if they believe the suspect could have information about an imminent threat to public safety.

That exemption allowed investigators to interrogate Tsarnaev while in custody, without informing Tsarnaev of his rights to a lawyer and his right to stay silent.

According to an AP report, after 16 hours of questioning, a representative of the United States Attorney’s office read Tsarnaev his Miranda warning, and the suspect stopped talking to investigators.

Related Story: Constitution Check: Are there limits on questioning a bombing suspect?

The “Miranda” in the Miranda warning was Ernesto Miranda. He was arrested in March 1963 in Phoenix and confessed while in police custody to kidnapping and rape charges. His lawyers sought to overturn his conviction after they learned during a cross-examination that Miranda wasn’t told he had the right to a lawyer and had the right to remain silent. (Miranda had signed a confession that acknowledged that he understood his legal rights.)

The Supreme Court overturned Miranda’s conviction in 1966 in its ruling for Miranda v. Arizona, which established guidelines for how detained suspects are informed of their constitutional rights.

The Miranda warning actually includes elements of the Fifth Amendment (protection against self-incrimination), the Sixth Amendment (a right to counsel) and the 14th Amendment (application of the ruling to all 50 states).

However, there are common misunderstandings about what Miranda rights are, and how they can protect someone under criminal investigation.

First, there isn’t one official Miranda warning that is read to a suspect by a police officer. Each state determines how their law enforcement officers issue the warning. The Supreme Court requires that person is told about their right to silence, their right to a lawyer (including a public defender), their ability to waive their Miranda rights, and that what they tell investigators under questioning, after their detention, can be used in court.

The Miranda warning is only used by law enforcement when a person is in police custody (and usually under arrest) and about to be questioned. Anything you say to an investigator or police officer before you’re taken into custody—and read your Miranda rights—can be used in a court of law, which includes interviews where a person is free to leave the premises and conversations at the scene of an alleged crime.

In fact, Ernesto Miranda came into a Phoenix police station voluntarily to answer questions in 1963 and also took place in a police lineup.

The police can ask you questions about identification, including your name and address, without a Miranda warning. And they can use any spontaneous expressions made by you as evidence—for example, if you say something without the prompting of police before you’re taken into custody.

Of course, you’re still protected by your Miranda rights—after you’re detained—even if you waive them after an arrest. At any time, during an interrogation, you can stop answering questions and ask for a lawyer.

In the case of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, investigators probably felt they had enough evidence to charge him and win a case in court without any of the information Tsarnaev volunteered before he was read his rights.

As for Ernesto Miranda, though his original conviction was set aside by the Supreme Court ruling, he was retried and convicted, and was in jail until 1972–then in and out of jail several more times until 1976. After being released in 1976, he was fatally stabbed during a bar fight. His suspected killer was read his Miranda rights and didn’t answer questions from police. There was never a conviction in Miranda’s death.

Scott Bomboy is the editor-in-chief of the National Constitution Center.

Recent Constitution Daily Stories

Video: The Fourth Amendment yesterday, today and tomorrow

The man who wrote the words “We The People”