Coinbase Wants To Be Too Big To Fail

THE NEW TITANS OF FINANCE prowl a glass fortress 3,000 miles from Wall Street. High above San Francisco’s Market Street, their headquarters take up three floors with sweeping views of the bay and city below. The reception desk bears jars brimming with chocolate coins near a jokey “Initial Chocolate Offering” sign. Beyond it, in an open space with no corner offices, big shots poached from Silicon Valley giants sit beside junior hires clutching free cans of LaCroix. This is the home base of Coinbase, the buzzy startup that wants to rewire the financial system around blockchains and digital currency.

But good luck finding it. There’s no logo outside the building or in the lobby. Nor is there any signage in the hallway outside that reception desk, just fortified metal doors and an intercom. Coinbase employees maintain a low profile, they explain, because most own virtual cryptocurrency, some in quantities that make them multimillionaires on paper. A kidnapper could capture someone and “pull out their fingernails,” a staffer says, to learn the location of their fortune—as if betting your career and well-being on a volatile, unproven financial technology weren’t stressful enough.

Such is life at Coinbase, a company where the mood alternates between upbeat and under siege. It was founded in 2012 as an exchange that lets individuals and companies easily buy and store digital currencies, most notably Bitcoin. And by 2017, when investor interest in those currencies moved to the mainstream, Coinbase was perfectly positioned to capitalize, becoming a 21st-century Wells Fargo for a new digital gold rush.

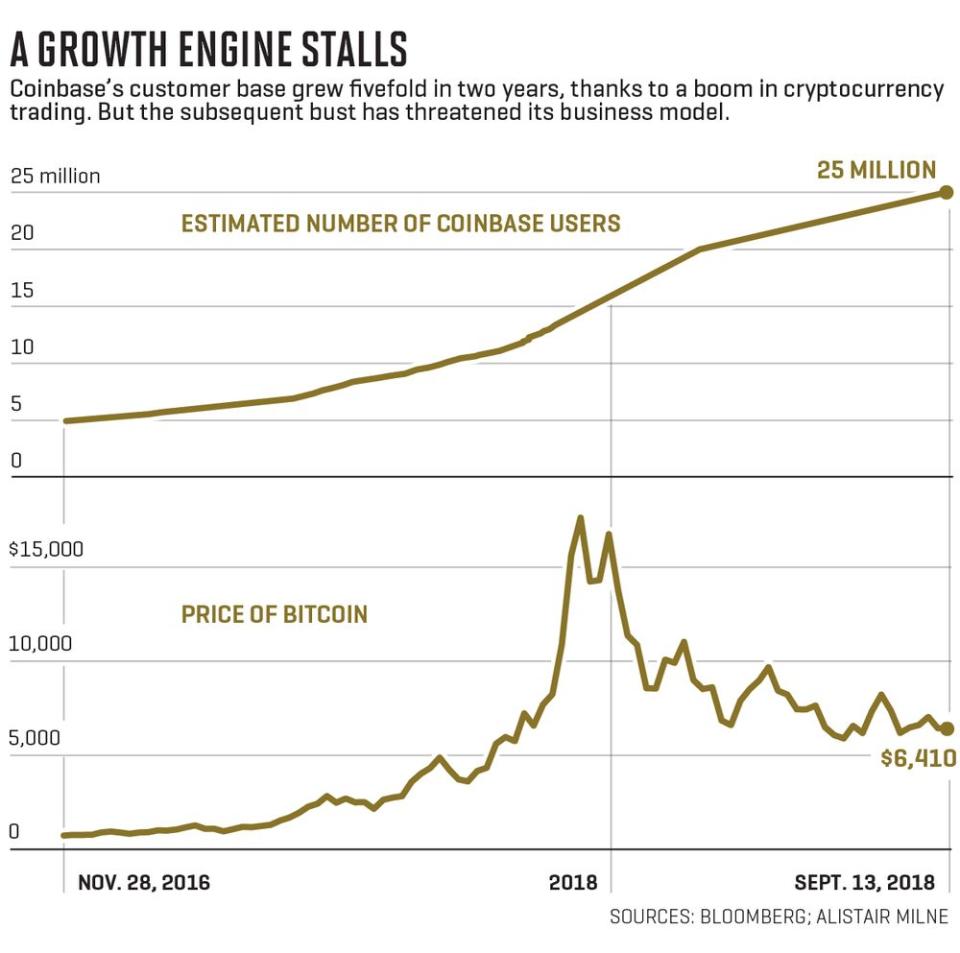

In short order, Coinbase became the first U.S. cryptocurrency startup to earn a $1 billion “unicorn” valuation from investors, and the first to bring in $1 billion in annual revenue. (The still-private company is profitable, according to regulatory filings, though it won’t disclose specific earnings.) Coinbase now claims 25 million customer accounts—a five- fold increase from two years ago—putting it on a par with traditional finance giants like Charles Schwab and the brokerage arm of Fidelity. The tech press is buzzing about new, higher-valuation funding rounds and a looming IPO. And the company’s first-mover status has made it something of a home planet for the universe of crypto-oriented business; a surprising number of top industry figures are connected, in one way or another, to Coinbase and its 35-year-old founder and CEO, Brian Armstrong.

Still, life at the top is tense. Coinbase owes its preeminence in part to last year’s unprecedented speculative surge in cryptocurrency investing. Today the buoyant Bitcoin runs of 2017 seem a distant memory, as more investors question the value of assets that have yet to prove their staying power. Many of the most popular digital currencies trade 80% or even 90% lower than their peaks last December, and the popping of the bubble has erased a staggering $600 billion in market capitalization. The collapse has meant less trading and less commission revenue for Coinbase, even as new low-fee competitors threaten to turn the company’s core service into a commodity—and even as the company recovers from self-inflicted problems that alienated customers during the boom.

Presiding over all this is an introverted founder who sees the cryptomania of 2017 as just one chapter in a longer story. Armstrong belongs to a generation of evangelists who view digital currencies, and the blockchain technology on which they’re based, as tools that will make investing, borrowing, and saving money faster, cheaper, and more egalitarian. And he wants Coinbase to become the banking empire that brings those tools to the masses.

Armstrong and his colleagues have laid the groundwork for that future, carefully wooing regulators and investing in new technology. What he hasn’t done yet is convince the wider financial world that crypto is a must-have technology. If Armstrong can’t eventually make a compelling long-term case, it may be not just Coinbase that crumbles, but an entire industry.

GROWING UP IN SAN JOSE, Armstrong often felt bored and confined. His parents, both successful engineers, provided a comfortable upbringing and a brisk intellectual environment. But while Armstrong saw the Internet as a tool to change society—in the same way Apple’s Steve Jobs and Intel’s Andy Grove who built their empires minutes from his househad done with computers and chips, two decades earlier—he fretted that others had beat him to it. “By the time I graduated from college and I was starting to work, I felt maybe I was too late—this Internet revolution had happened,” he said.

Armstrong arrived early, however, for the genesis of a different revolution. While surfing the web at his parents’ house on Christmas of 2009, he encountered a nine-page paper written by a pseudonymous author named Satoshi Nakamoto. The idea it described—a global currency beyond the reach of banks or governments—was so compelling he began to read it again, tuning out his mother’s entreaties to join the holiday festivities downstairs.

Nakamoto’s paper is now famous for describing the architecture of Bitcoin—and the broader notion of using a global network of computers to maintain a common record of any kind of transaction. Like other early believers, Armstrong became enamored of the idea of a financial system that could minimize the influence of middlemen and politicians. His fixation grew after a trip to Argentina. He recalls sitting in restaurants in Buenos Aires where prices on menus were covered with stickers that changed almost daily—symptoms of rampant inflation that had wiped out the savings of ordinary people. Bitcoin, he thought, represented a way to store or transfer wealth beyond the control of rapacious states. It was digital gold.

For this vision to come to pass, though, ordinary people would have to use crypto- currency—and in its early days, that was wildly impractical. Would-be Bitcoiners had to engage in a recondite rigmarole of downloading “wallet” software and then funding the wallet with an offshore bank transfer or working with shadowy middlemen.

Armstrong’s vision was to make the process more akin to buying stock online. In 2012, he left his job as an engineer at Airbnb to make it a reality. He designed Coinbase to allow customers to use traditional bank accounts to purchase cryptocurrency. Whereas buying Bitcoin had once required serious tech chops, the Coinbase version was more like using PayPal or Venmo. And instead of requiring users to store currency using complicated cryptographic keys, Coinbase stored it on customers’ behalf.

There turned out to be plenty of demand for an easy-to-get Bitcoin service; barely a year after launching in late 2012, Coinbase reached the million-customer mark. At a time when concerns about drug dealing and money laundering hovered over the crypto world, Coinbase took pains to comply with know-your-customer laws and other strictures of U.S. banking law. And during last year’s mania, as hundreds of new crypto “coin” investments sprang up, the company—fearful of scams or trouble with the Securities and Exchange Commission—declined to sell the vast majority of them. (Today there are 15 cryptocurrencies with a market cap over $1 billion, but Coinbase offers trading in only five of them.) Fretting about compliance didn’t endear Armstrong to the crypto world’s self-styled renegades, whose tastes run towards cocaine, Lamborghinis and anti-government diatribes. But it has put Coinbase on the cusp of regulatory approval for a broker dealer license. It is also in talks to obtain a federal banking charter—a once unthinkable idea for any Bitcoin-related company.

“What matters in financial products is the first-mover advantage and who sets the standards,” says Christian Bolu, an analyst with Sanford C. Bernstein. “Coinbase is assuming that mantle and setting the regulatory agenda.”

The company is also a darling of blue-chip venture capital firms, including early investors Union Square Ventures and Andreessen Horowitz. The latter’s $25 million investment in 2013 came as the VC community’s first truly big bet on cryptocurrency. The young CEO, his backers say, quickly revealed an instinct for self-improvement. “Every meeting you have with him, he sends follow-up questions,” says Chris Dixon, a partner at Andreessen. “He’s constantly curious and looking for mentorship.” Armstrong’s bid to better himself is almost pathological. Last year, he obtained his pilot’s license but largely lost interest upon becoming satisfied he could fly a plane. At Coinbase, Armstrong will grill employees about what he, and they, could do better: He once emailed his performance review from HR to the entire staff in order to solicit tips.

He consumes large numbers of books, mostly by audio. His tastes include science and behavioral psychology, but lean to management bromides and great man biographies (Steve Jobs, the Wright Brothers, Dwight Eisenhower). Reading Michael Malone’s Bill and Dave, a history of Hewlett-Packard, prompted Armstrong to urge employees to approach him anytime with ideas, lest someone else snap them up. “Steve Wozniak, when he was an engineer at HP, brought them the Apple 1,” Armstrong recounts. “He’s like, ‘I built this, I think HP should manufacture it.’ And they said no. And, of course, then he left and created Apple Computer, right?” Armstrong’s nightmare, it seems, would be for success to elude him after being right under his nose.

BUT WHEN SUCCESS did arrive, Coinbase and Armstrong found they had a lot to learn about managing it. In 2017, as Bitcoin and other digital currencies rose 20-fold or more in value, Coinbase made a killing on trading fees. During the height of the mania, Armstrong has said, Coinbase signed up more than 50,000 new customers a day. This led the company’s website to crash and sputter and leave the site’s engineers to feel like they were holding back an avalanche with Saran Wrap. For some Coinbase customers, the site became a hellish experience, as glitches reigned and orders went unfilled. Twitter and the website Reddit lit up with anguished accounts of money stuck in limbo and customer service tickets landing in black holes, unresolved for days. Dozens of other customers filed complaints with the Better Business Bureau and the SEC.

Hackers, meanwhile, began targeting customers with elaborate phishing and bank fraud scams; Coinbase was at one point spending 10% of its revenue on resolving fraud-related issues. Employees weren’t happy, either. The chaos left many engineers and customer service reps working 18-hour days, and some quit in exhaustion.

Another serious hiccup occurred on June 21, 2017, when a high-net-worth “whale” abruptly sold millions of dollars’ worth of the popular currency Ethereum. The result was a “flash crash,” as prices plunged from $320 to under 10¢ before shooting back up again, triggering automated sell orders that resulted in some unlucky investors ditching their whole position for a pittance. Unlike most big stock exchanges, Coinbase hadn’t built a trip wire to halt trading in the case of a panic selloff—a big technical blunder. Armstrong eventually decided to rescue the victims by canceling their side of the trades—a calm-restoring but costly proposition.

At the peak of the crypto boom, Coinbase took another hit to its credibility over its handling of Bitcoin Cash, a spinoff of Bitcoin. It initially declined to support the new cur- rency, then reversed its position after a wave of customer complaints. But in December, just before Coinbase announced the reversal, there was a sudden, unusual uptick in Bitcoin Cash’s price—sparking speculation that Coinbase employees had traded on inside information and bought the currency in anticipation of an influx of new money. According to a former employee, the outcry led Coinbase to abruptly delete two of its channels on the messaging app Slack, which employees used to discuss the crypto market and trading strategies.

Coinbase concluded after an internal investigation that its employees had not engaged in insider trading, and the company tells Fortune it closed the Slack channels out of an abundance of caution rather than any wrongdoing. Given the evolving regulatory regime around cryptocurrency, it’s not clear that trading the currencies based on inside information would even be illegal. Still, the controversy, combined with the site’s customer service woes, sent a message: Just as cryptocurrency was commanding a national spotlight, Coinbase seemed unready for primetime.

Its struggles didn’t scare away investors, however: In August 2017, the startup raised $100 million, giving it a $1.8 billion valuation. That provided Armstrong with the capital and clout to hire talent that could help him right the ship. Coinbase poached longtime Twitter operations executive Tina Bhatnagar to help repair its customer service shambles, and it brought on HP veteran Asiff Hirji as COO. Armstrong has also committed to hiring inclusively: Coinbase, by company rule, interviews three qualified people from underrepresented backgrounds for each open position at the VP level and up, and 33% of leadership roles are held by women.

Employees give their boss high marks for staying on an even keel as the crises unfolded. Armstrong himself believes he found his footing as the company grew. At first, he recalls, “I thought [a CEO] had to be a military general, barking orders. But I feel I’ve embraced my own style of leadership, which is a little bit more collaborative. It’s seeking the truth, not trying to be right. I also realized you shouldn’t try to be something you’re not because that’s the worst kind of leadership.”

Coinbase has also doubled its headcount over the past year to nearly 1,000. The extra staffing has helped restore work/life balance and reduce the number of all-nighters. Arm- strong, for his part, is showing his staff that he too can chill out. This includes recapturing some of the vibe from the company’s early days. Back then, Armstrong and Coinbase’s third employee, Olaf Carlson-Wee (who today runs Polychain Capital, the largest U.S. crypto hedge-fund) would team up in epic Halo matches against co-founder Fred Ehrsam, a former high school gaming champ. There was also a lot of ping-pong and rock-climbing. Today’s version of chilling out includes Armstrong indulging his penchant for belting Disney songs in the office and at off-site karaoke. One staffer (who calls Armstrong a “great singer”) described the CEO leading a recent Little Mermaid sing-along at a bar in San Francisco’s Castro District.

Customer service, meanwhile, has improved dramatically under Bhatnagar, says Mike Dudas, a Google veteran who runs a crypto-news startup The Block. By mid-2018, Coinbase claimed to have eliminated 95% of its backlogs, and it says it responds to complaints within 10 hours—a far cry from the peak of the Bitcoin mania, when many tickets took a week or longer to resolve.

Of course, if complaints are a far cry from where they were, that’s because Bitcoin mania is too. Cryptocurrency prices have lost more ground since December in percentage terms than the Nasdaq did during the dotcom bust of 2000–02. The research firm Diar recently reported that Coinbase trading volume has dropped from over $20 billion in January to less than $5 billion a month this summer. Since Coinbase charges commissions that range up to 1.99% of the value of each trade, the simultaneous plummeting of values and volumes is a double whammy. And its margins are under threat from new competition. Over the past year, fintech companies Robinhood and Square and European brokerage eToro have wooed crypto investors with low- or no-cost trading. That ominous drumbeat adds urgency to one of Armstrong’s biggest missions: converting Coinbase into a diversified blockchain-banking giant that isn’t solely dependent on trading revenue.

IT’S A SWELTERING EVENING in Washington, D.C. as Armstrong, clad in a tan suit, sits down for dinner. He and a small retinue are gathered in a hotel restaurant near Dupont Circle, where the food is both expensive and mediocre. Tucking into poached salmon, he reflects on his day meeting lawmakers and senior regulators. Armstrong, ever the Silicon Valley engineer, is not wowed by the political atmosphere. “I think my favorite part was the underground train,” he says, referring to the hidden monorail that whisks elected officials and elite visitors to and from the Capitol. Still, the CEO and his team have been persistent in educating the political class about cryptocurrency and blockchains. And these efforts are paying dividends, as more regulators see the technology as a useful tool rather than an inherently criminal threat—opening more opportunities for Coinbase and its competitors.

In addition to its impending broker-dealer license, Coinbase has won permission to provide custody services for big institutional customers that wish to own cryptocurrency assets. These services could prove lucrative if the company can lure more big players like mutual funds, pensions, and private equity funds to trade with it. There’s already some progress on this front: Earlier this year, its services aimed at professional traders and institutions—primarily wealthy “family offices” and cryptocurrency oriented hedge funds—surpassed its consumer platform as the company’s biggest source of trading volume.

“I don’t think it’s going to be easy,” cautions Richard Johnson, a financial technologies expert with consultancy Greenwich Associates. “The institutional market will be a different one for them to crack,” especially since mainstream fund managers are waiting for a stronger regulatory framework before investing.

But recent acquisitions could help Coinbase be ready when that framework emerges. One of its recent hires is Emilie Choi, VP of corporate and business development, who presided over 40 acquisitions at LinkedIn. Since signing on in March, Choi has helped Coinbase snap up nearly a dozen small blockchain and financial firms that could help it provide a broader range of services. Still, for a company that likes to style itself as “the Google of crypto,” Coinbase is still waiting for an encore hit to its trading platform, along the lines of Google adding Gmail or Maps or YouTube to its core search service.

Right now, Coinbase’s most promising project, say Johnson and others, involves a new class of investments known as security tokens, which represent investable assets as tokens on a blockchain. Armstrong has spoken of building an alternative investment market around such tokens, run by Coinbase. Supporters say tokens could be used to convert assets that are relatively illiquid and expensive—privately held companies, for example, or art and other collectibles—into units that are easy to trade.

Trying to understand security tokens and their implications is much like trying to grok the Internet in 1994. Just as people were puzzled by terms like “browser” two decades ago or “app” a decade ago, the vocabulary of blockchain—including “tokens” and “wallets”—is still baffling to many. One of the industry’s better explainers is Coinbase CTO Balaji Srinivasan, a charismatic 38-year-old with spiky hair, salt-and-pepper stubble and eyes that glisten. Srinivasan has written a series of influential essays on tokens’ potential to remake the venture capital industry.

“Blockchains are the most complicated piece of technology since browsers or operating systems,” he says, adding that only a handful of savants possess the expertise in a range of fields—including cryptography, game theory, networking, databases, and cyber-security—to wrangle them. But tokens are different, he explains. They can be built by a much broader class of engineers, while still taking advantage of blockchains’ powerful attributes, such as being tamper-proof and indestructible. And when used to securitize assets, they represent an efficient new way to recognize and distribute ownership.

David Sacks, the venture capitalist and founding COO of PayPal, sees U.S. real estate— a $7 trillion market that is highly illiquid—as particularly ripe to be subdivided and sold via tokens. “It’s like going from an analog to a digital system of ownership. Today, a deed or private security is a piece of paper in a file cabinet somewhere. A token digitizes it,” said Sacks, who is backing a company called Harbor that creates code to ensure tokens comply with security laws. The real estate idea is already moving from theory to reality: The owners of the upscale St. Regis in Aspen, for example, announced in August that they would sell a 19% stake in the hotel in the form of tokens.

Preston Byrne, a financial consultant and cryptocurrency lawyer, argues that the security tokens will make it easier for businesses to raise capital, by streamlining regulatory compliance and record-keeping—as information that currently occupies dozens of disparate files gets consolidated onto blockchains. Tokens could also make companies less reliant on investment banks and other middlemen, slashing the costs associated with mergers, acquisitions, and the issuance of equity or bonds. “Coinbase is in a very good position to leverage all that because they’ve got the tech,” Byrne says. “This is where the rubber hits the road, as tech startups start eating big banks’ business.”

The big banks, of course, may eat before they get eaten. Flush with cash and stocked with their own tech talent, financial monoliths like JPMorgan Chase and Citigroup are funding their own blockchain projects. And Coinbase hardly has a monopoly on crypto- currency trading technology; rivals including Circle and Gemini are also jockeying to build institutional trading platforms.

Still, Coinbase remains an investor favorite. Multiple sources confirmed to Fortune that the company is in the final stages of a hefty funding round. In April, when Coinbase acquired crypto company Earn.com, reports leaked that Coinbase projected its own value at about $8 billion. The company has not confirmed that figure but doesn’t dispute it.

As for the broader cryptocurrency revolution, Armstrong hasn’t lost sight of the ideal of a global payment system independent of banks and governments. To this end, Coinbase is building software called Coinbase Wallet to help ordinary investors navigate the world of tokens. And Armstrong remains even more ambitious than his investors. “I really want to see crypto be used by a billion people in the next five years,” he says.

This article originally appeared in the October 1, 2018 issue of Fortune. (An earlier version of this article misidentified the title of Fred Ehrsam).