Closure of Arizona plant symbolizes the demise of coal and its human toll

NAVAJO NATION – The pending closure of a massive coal plant here isn't measured only by better air quality or the cost savings for the power companies that own it.

The aftereffects include hundreds of jobs lost in an area where high-paying work is hard to find. The lives disrupted and families scattered.

The looming shutdown of the Navajo Generating Station forced hundreds of utility employees to relocate to new jobs and put most of the region's miners out of work when the Kayenta Mine that fueled it closed in August. Most are Native American.

The Navajo Nation and Hopi Tribes had to patch gaping holes in their budgets. Page, with its largest employer departing, had to double down on tourism.

The demise of coal in the region brings environmental benefits but also requires years of remediation work at the power plant and the mine that supplied it.

The power plant's closure, which is likely in November, signals a warning for other coal mines and plants, dozens of which are likely to close in the West in coming years. Despite the best efforts of politicians from the U.S. president to tribal leaders to keep the plant open, it couldn't be saved.

The same economic forces that closed it are bearing down on other coal communities.

T-Mobile/Sprint merger: FCC formally approves deal, but companies aren't out of the woods yet

Netflix feeling confident: Company says they're not worried about Disney Plus and Apple TV Plus

Lives have been uprooted. Like Marvin Russell, a young worker laid off from the Kayenta Mine. He lives in Utah now, nine hours from his home on the Navajo Nation, while his wife finishes college.

Like Grace Antone, who worked at the Kayenta Mine for 21 years and comes from a family of miners. She doesn't plan to leave her home and worries she won't find a reliable job nearby.

Like Jerry Williams, a 38-year power plant employee who now works at a Salt River Project facility near Phoenix. Most weekends, he makes the five-hour drive to the Navajo Nation for his family and to the tribal chapter house where he is president.

Like Michael Bigman, who would mark his 40th year at Navajo Generating Station in January. Rather than relocate for a new job, he hopes to work decommissioning the plant and then retire.

Theirs are just a few stories among the hundreds of people touched by the closures – an economic tsunami many hoped never would happen.

History of the Navajo Generating Station and Kayenta Mine

Page was established in 1957 as a housing community for workers building the Glen Canyon Dam, but it wasn’t incorporated until 1975, a year after the first of three generators opened at the nearby Navajo Generating Station.

The coal-fired power plant offered a stable base for Page’s economy once construction of the dam was finished and before tourism grew into the industry for the region it is today.

The mine, some 78 miles east of the plant, also provided crucial employment for the people living on the Navajo and Hopi nations. Another mine in the same complex supplied the long-closed Mohave Generating Station near Laughlin, Nevada. The closure of that power plant and its mine in 2005 only magnified the economic significance of the remaining plant near Page and Kayenta Mine.

Power from the coal plant was divided among the utilities that owned it and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, which used its share to power pumps on the Central Arizona Project canal, moving water from the Colorado River to Phoenix and Tucson.

SRP runs the plant for the other owners, which include Arizona Public Service Co., Tucson Electric Power Co., NV Energy and formerly the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power.

SRP fought for years to keep the coal plant running while environmentalists argued for stricter controls to mitigate haze and other pollutants. When LADWP pulled out of the plant, SRP agreed to buy its share to keep the plant running.

SRP negotiated a deal to close one-third of the plant to comply with environmental regulations that many believed would allow the plant to keep running through 2044. But a boom in cheap natural gas around the country, as well as increasingly low-cost renewable energy, prompted the owners to vote to close the plant by the end of 2019.

Operators of the CAP canal said they would save money with the closure.

Besides the jobs and obvious economic benefit of the facilities, the plant and mine help the communities in myriad other ways. These include donations power plant workers make to community organizations, and the coal previously provided to Native Americans who drove from far and wide to fill their truck beds and use the fuel to heat their homes.

The decision to power down the facilities is not unique to this coal plant. Throughout the U.S., utilities retired 546 individual coal generators from 2010 through early 2019, according to the Energy Information Administration.

Ample opportunity or lack of transition time?

Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez said the closure of the plant and mine would reduce revenue by an estimated $30 million to $50 million.

In its $1.3 billion 2020 fiscal year budget, Nez said the nation was able to overcome that deficit.

"We utilized some of our reserve and some of the other funds available," he said.

This resulted in a slightly smaller $167 million in general funds for the Navajo Nation for 2020. Last year, the nation's budget was $172 million.

Besides the loss of revenue, Nez acknowledged the region will lose jobs because of the closure and said he is working with his directors of the Division of Economic Security and Development of Human Resources to ensure that mine and plant employees have options afterward.

Coconino County, which includes Flagstaff and Page, has a jobless rate of 6.5%, but that leaps to nearly 9% in Navajo County and is approximately 50% on the Navajo Nation itself.

The Nez administration's efforts to ease employment worries include educating workers about other employment opportunities with the Navajo Nation government as well as providing them with information on how they can develop a small business.

"There (are) a lot of opportunities for small Navajo businesses," Nez said.

Many of the workers are trained engineers and have years of experience, Nez said. He said he encourages them to consider developing their own businesses so they can bid on Navajo Nation projects.

"That would keep our Navajo people home, they wouldn't have to leave the nation and would keep the dollars within our nation," he added.

The mine and power plant employed about 750 people combined before they began to wind down operations in 2017.

"Yes, there are jobs that are affected by it, but there is also a transition that we need to do to provide other opportunities," Nez said. "There is a move to be better stewards of our land and for Navajo people. Our land is our life, so we got to take care of our land. We have to keep that in mind for the future generations of our people."

But has there been enough time for workers to transition into new jobs?

"The workers did have ample time to know that the plant was going to close," Nez said.

Navajo Nation Council Delegate Nathaniel Brown, who represents the Chilchinbeto, Dennehotso and Kayenta chapters, disagrees.

"No matter what, there is not going to be enough time," he said.

Power plant workers at the Navajo Generating Station had better options because SRP offered a job to each plant worker, while the mine operators did not. The miners weren't prepared, Brown said. Leadership "dropped the ball," with no plans in place to help the workers.

"We should've been more proactive," Brown said. "We should've had different options available up there for the miners, community and their families."

Now, families and communities once sustained by the power plant and mine face a tough decision: leave their homes for work far away or stay and hope to find work in a land where jobs are scarce.

'I wanted to stay on the Navajo Nation'

Marvin Russell, 29, didn't want to move away from the Navajo Nation. He grew up in Whitegrass, Arizona, only a half-mile from the main access road for Kayenta Mine. It takes him about 10 minutes to drive there.

His family relocated to Logan, Utah, as the closure was pending, and he joined them after the mine closed Aug. 26.

Russell is a certified diesel mechanic. He started working for the mine in 2014 as a driller and blaster, an ideal job because it allowed him to stay near his family.

Russell said he wants his 5-year-old daughter to grow up how he did – near livestock and surrounded by family rather than in a city, visiting the Navajo Nation only occasionally.

"(I want her) to know where she comes from," he said. "I wanted my daughter to be around her family."

Moving away from the Navajo Nation also meant moving away from his 55-year-old mother, Pauletta Russell.

"My mom doesn't like the city," Russell said.

The decision was especially tough on her; she likes to stay home and be near her livestock, he said. His seven siblings are all away from home, and her help is limited to his 78-year-old grandmother, who lives up the road.

"That's just where she wants to stay and that's where she calls home," he said. "That's where I want to be, too."

Once the Navajo Nation Council voted against buying the plant to keep it open, Russell knew he needed to start putting away as much money as he could and work as many weekends as possible. By June, the mine stopped offering weekend shifts, so he tightened his budget and continued to save until he was laid off.

That day, Russell said, he felt a heavy weight in his heart. All the work lockers were closed and the older workers were saying their goodbyes as they left. The reality of the situation, the mine shutdown, was weighing on him.

"It was really sad," Russell said. "I highly relied on my job."

His salary supported his wife and daughter but also his extended family. When his family needed some extra money to buy feed for their livestock, he would provide it.

The day after he was laid off, Russell joined his wife and daughter in Logan. They had moved Aug. 1, and his wife enrolled at Utah State University to finish her bachelor's degree.

The family originally decided Russell would continue working at the mine, and when possible, he'd visit his family in Logan every other weekend.

"I wanted to stay on the Navajo Nation. That is one of my main goals, to stay on the reservation. It's home," Russell said. "Out here (Logan), it's not home. We're like tourists here."

Russell wants his family to return to the Navajo Nation, but right now, he'll continue to look for work in Logan while his wife goes to school.

Like a lot of workers affected by the closure, Russell tried to stay positive, hopeful he'd get to keep working. He wanted to be able to walk away from his mining job with a pension and health benefits, like some older workers.

"This is where we want to retire, this is where we want to build a house," he said. "This is where our heart is."

Weeks shy of earning a pension

Like many, Grace Antone, 50, hoped the Navajo Generating Station and the Kayenta Mine would never close. She wasn't prepared for it, and she believes the Navajo Nation is still not ready for the effects of the closure.

"I didn't really have a plan because I was really hopeful," Antone said. "It was very disappointing to us how the Navajo Nation wasn't really supportive of the mine."

She advocated for the mine and plant to be kept open and was present the day the Navajo Nation Council voted on the purchase of the plant, which would also have kept the mine running. She said seeing the delegates vote against buying the plant felt like they didn't care about the workers.

"We didn't mean anything to them," she said. "The Navajo Nation Council delegates didn't care about the rest of us who are still here."

Antone lives in the Whitegrass area with several family members who also work for the mine. Russell is her nephew. She took the same route to work every day for the nearly 21 years she worked at the mine. She was a contractor for 16 years before officially being hired by Peabody.

Her job at the mine allowed Antone to give her three children a comfortable life and support them as they went to college. It's why she started working there in the first place.

"I was very comfortable, and I enjoyed the fact that we do have a place to live, and my children were comfortable," Antone said.

Working at the mine, Antone set goals to earn a pension and keep her health benefits, just like her late father, who was a miner. When he retired after 25 years, Antone said, he got a full pension and health benefits.

"We want to live comfortably; we want the dream like everybody else," she said.

She won't reach her goals. Antone needed to be employed five years to earn a pension. On Aug. 26, she was laid off, about 1,000 hours shy of earning it.

"I wasn't able to earn my pension," she said. "Just a few more years and we could've had it."

In addition to her pension, she's losing her health benefits. Antone said she's already lost her dental and vision insurance, and in about 11 months she'll be without medical insurance.

Antone has looked for work since she was laid off, but has had no luck. She has searched in the area near Kayenta, choosing not to look into work at other mines, which might be farther away.

"Right now I'm trying to look for work to where I can stay home, but I haven't found anything yet," she said. "I think I would have to leave."

Two of Antone's children live in Flagstaff and another in Colorado Springs. She doesn't plan on living with them because she wants to stay at home with her husband, Jacob, in Whitegrass. She's waiting to see how things work out.

"This is home," she said. "I never thought we would have to leave. I don't have a home anywhere else."

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW: Impacts of the closure of the Navajo coal plant and mine

'I'm always packed'

Jerry Williams wakes up at 3:45 a.m. to get ready for work Monday through Thursday. He climbs into his truck and takes the hour-long drive from his son's apartment in Ahwatukee to his job at SRP's Mesquite Generating Station west of Buckeye.

For about a year, Williams has worked in the Phoenix area as a planner and scheduler. He accepted SRP's relocation offer after 38 years at the Navajo Generating Station.

Williams' wife didn't relocate, preferring to stay in Page. Williams returns home on weekends, usually Thursday to Sunday. Then he makes the nearly five-hour drive back to Phoenix on Sunday night.

As a chapter president for the tribe, he has to be back before 6 p.m. on the first and second Thursdays of each month for meetings. There are times when Williams is not able to do that because of the travel time.

"I'm always packed," Williams said. He carries a bag with four days of work clothes. On Thursday morning, that bag is packed, ready for the drive home.

When he took the job, Williams thought relocating was a good idea. He wanted to do what was best for his family, but now he's looking into retirement.

"It's hard for me to leave on Sundays because of my wife," he said.

He's thinking about retiring by the end of the year or in the spring of 2020, when he turns 60.

Williams said when he was interviewed for his job at the new plant, his boss asked him where he would be in five years. His answer? Back in Page.

In Page, Williams said he was able to coach middle-school basketball and volunteer at the local addiction recovery center. Now, he'll be lucky to get in a few hours of volunteer time when he's home on weekends.

It might not be so hard if he were younger, Williams said, because then there would be more for him to enjoy in Phoenix.

But Williams is going to be a grandfather soon, for the first time. He hates seeing the tears in his wife's eyes as he leaves every Sunday.

'It's too late for me to move'

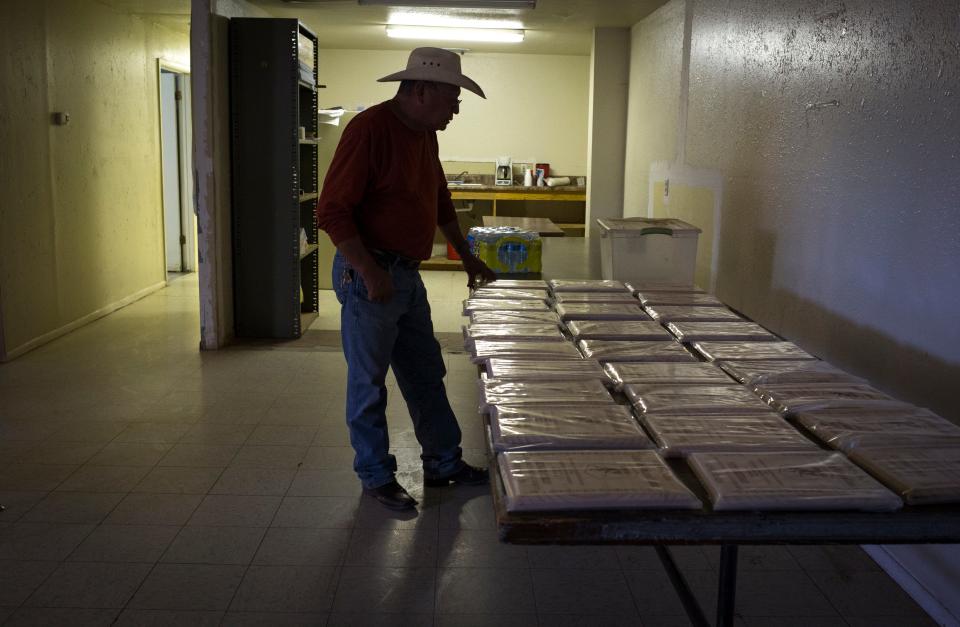

Michael Bigman walks through the shop area in the Navajo Generating Station and greets a half-dozen workers by name as he passes their stations.

Bigman plans to celebrate his 40th year at the plant in January. Because of his seniority, he expects to be able to stay on during the decommissioning. He will retire once the work runs out, rather than relocate.

"It's too late for me to move," Bigman said.

He has deep connections to the plant – two of his sons worked there. One took a job with SRP in the East Valley, and the other moved to Buckeye to work at a gas plant in the Gila Bend area. Both of their families moved with them, Bigman said.

His sister-in-law worked at the Kayenta Mine for more than 30 years. His daughter once worked at the power plant and now works in the Phoenix area. He even has a grandson who worked at the plant. His son-in-law works as a lineman after being hired at the plant years ago to work on an overhaul.

Outside of attending high school in Utah, Bigman has rarely left the Page area. He was first hired at the plant as an apprentice and has stayed since, raising five children and 11 grandchildren in the area.

"Hopefully, the tourism industry picks up more," Bigman said.

He said many of his friends from work have taken new jobs with SRP.

"They had mixed feelings, but most of them redeployed," he said. "The younger kids are well adapted. It's us older folks who got used to the plant. The mine and the plant have been good for us. The plant gave us a lift."

Reporter Shondiin Silversmith covers Indigenous people and communities in Arizona. Reach her at ssilversmi@arizonarepublic.com and follow her Twitter @DiinSilversmith.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Navajo Generating Station, Kayenta Mine closings show demise of coal