Climate change could threaten the world's beer supply. Do you care about global warming now?

Some 10,000 years ago, after the frigid Ice Age ended, humans tamed the nutritious grain, barley.

It blossomed in a fertile realm of early civilization spanning contemporary states like Israel, Palestine, Jordan and beyond. Then 5,000 years later, peoples in the Zagros Mountains of modern-day Iran learned to brew barley beer. Today, farmers globally harvest tens of millions of tons of the crop each month.

But barley, like many crops, has a flaw: Its yields plummet during heat waves and drought — both extreme consequences of a warming planet. As a primary ingredient in beer, this poses a real threat to the future global supply of frothy ales, lagers, and stouts.

“The extremes are detrimental to just about every crop — but barley is near and dear to just about everyone — or at least people who like beer,” Collin Watters, the head of the Montana Wheat and Barley Committee, a state organization, said in an interview.

And new research published this week supports Watters' barley observations.

Image: U.S. Department of Agriculture/Bill scruggs

A group of scientists from the United States, United Kingdom, and China have now forecast how barley harvests would be disrupted by different climate scenarios this century, which are dependent on how much heat-trapping greenhouse gases modern civilization pumps into Earth’s atmosphere.

In a study published Monday in the journal Nature Plants, the researchers conclude that if greenhouse emissions continue unchecked (often called “business as usual”), barley harvests will drop by 17 percent by the century's end.

Textbook economic consequences would follow.

With a choked barley supply and burgeoning population, beer prices would catapult: Today’s average six-pack in the U.S. would cost around $16, the researchers found. Beer prices would be jacked up by nearly 200 percent, or perhaps more, in stout-quaffing Ireland.

“Prices really skyrocket in a high-emissions world,” Nathaniel Mueller, a study coauthor who researches how environmental change influences agricultural systems at the University of California Irvine, said in an interview.

Barley has historically flourished under a stable and temperate climate system. But with temperature and heat extremes now increasingly stoked by the highest carbon dioxide levels on the planet in at least 800,000 years, both farmers and barley have real vulnerabilities.

SEE ALSO: Why scientists think cows could be the largest animals on land in 300 years

“At the end of the day, we’re really dependent upon favorable weather conditions, and farmers have located in places where conditions tend to be favorable,” said Mueller. “As the climate changes around them, they’ll be increasingly exposed to these extreme events.”

And when it comes to the future reckoning of droughts and heat waves, the science is strong.

“We have a high certainty of how things are changing,” Andreas Prein, who researches climate and weather extremes at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, said in an interview.

With higher temperatures, the world’s water cycle experiences more extremes. This is already occurring all over the U.S., in the south, California, the desert southwest, and beyond.

“You get strong rainfall in extremes, or you get nothing,” said Prein, who had no role in the study. “Floods and droughts — both are not good for farmers."

The vulnerability of barley

The problem isn’t simply that barley harvests fall during heat waves and drought. It’s that the barley used in beer — in a process called malting — has to be of a specific, vigilantly grown, high-quality.

“It really is this special crop that needs a certain set of growing conditions,” Watters, who wasn't involved in the study, said.

Barley used in beer-making, for example, must be low in protein. Warmer weather, or heat spells at an importune time in the growing process, can mean doom for a beer-worthy crop.

“Generally, the hotter and drier the climate is, that normally indicates higher protein,” said Watters. “And that is bad for making beer.”

“It’s more complicated than just a loss of production,” he added.

Image: u.S. Department of Agriculture

A spell of drought hit Montana barley farmers in 2017. “Around June 1, it was like someone just turned off the spigot, and we didn’t have rain for months,” said Watters.

Farmers with irrigation were able to contend with the dryness, but pumping water is hugely expensive, and it can’t always be relied upon. “It’s a finite resource,” said Watters.

Barley isn’t alone in requiring specific, consistent growing conditions. The coffee bean has already been hit with similar, well-documented struggles.

“It’s not just can you grow coffee somewhere — it’s can you grow good coffee,” said Prein.

Beer saviors?

Future barley crops aren’t necessarily imperiled — yet.

For one, the study found that under low greenhouse gas emission scenarios, barley crops — and ultimately beer prices — are only impacted in minor ways.

Accordingly, if global society can dramatically reduce carbon emissions in the next two decades — which would require a prompt and politically challenging transition to renewable energy paradigms — our beer supply will likely be alright.

“It’s in our hands what future we want to see,” said Prein.

What’s more, ancient farmers found ways to grow barley under new, unfavorable conditions. Beginning about 5,000 years ago during the onset of the Bronze Age, farmers increasingly left over-populated areas in the modern day Middle East and began to spread north, to colder climes.

They persevered, and found a way to successfully grow barley.

“A lesson from the Bronze Age is that it all depends on how much flexibility the farmers enjoy,” Xinyi Liu, an archaeologist at Washington University in St. Louis who researches prehistoric food cultivation, said in an interview.

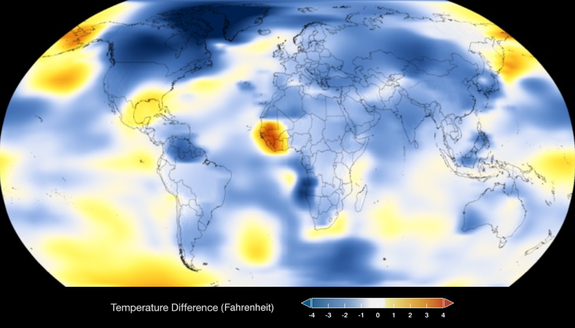

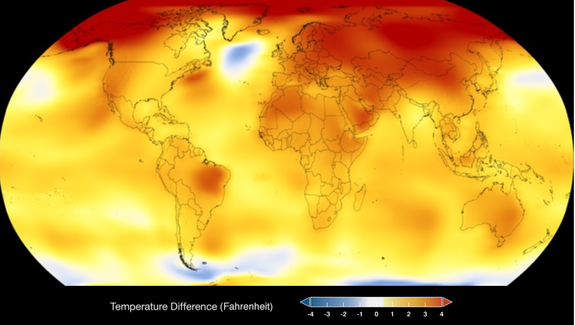

Image: nasa

Image: nasa

Back then, farmers capitalized upon a diversity of adapted barley varieties, known as “landraces.”

This diversity allowed them to find and develop strains that could withstand new, challenging growing conditions in places like northern Europe and the high-elevation Tibetan Plateau, said Liu. Of course, these were colder, not warmer, environments like the ones we're facing now.

Today, however, the industrial agriculture world is largely focused on barley varieties that produce consistently ample harvests — as opposed to maintaining biodiverse, potentially adaptable barleys.

“We’re now in an era of the higher yield varieties — that means less variety in the overall pool,” said Liu.

“The landraces have been overlooked by the modern scientific progress and so forth,” he added.

Though, more drought resistant barley varieties are in the works said, Watters. Breeding programs, like those in Montana, “try and build in some tolerance to adverse conditions,” he said.

In the end, if emissions persist as they are and farmers can’t adapt, the inevitable solution might be creating beer without barley.

“We should keep open-minded about what we can use to make beer,” said Liu, suggesting other grains like millets.

Already, major producers like Budweiser — for better or worse depending on one’s pallet — use rice along with some malted barley to brew copious amounts of beer.

The coming decade and beyond will be pivotal in determining the fate of the world’s beer supply, and critically, the future cost of beer.

Regardless of our climate path, farming and harvests will continue. And like they have in years past, farmers will still remain largely beholden to the whims of weather — but weather that is now unquestionably warming, disrupting the climate, and making things weird.

“They hope for the best, but anticipate the worst,” said Watters.

Update 10/15/18 at 12:50 p.m. ET: This story was updated to correct the modeled average price of a six-pack of beer in the U.S. under high-emission scenarios to $16. The price was originally quoted at $20.

WATCH: Ever wonder how the universe might end?