Clergy Abuse Advocates Fear Pope Francis Is Making It Harder For Victims To Speak Up

When Joelle Casteix heard Pope Francis accuse sex abuse victims in Chile of slander, the pontiff’s words hit close to home.

Francis told reporters Thursday that he hasn’t seen any convincing evidence against Chile’s Bishop Juan Barros Madrid, whom victims claim protected a pedophile priest.

“The day someone brings me proof against Bishop Barros, then I will talk,” Francis said during a papal trip to Chile, according to The New York Times. “But there is not one single piece of evidence. It is all slander. Is that clear?”

Casteix, a California native and advocate for abuse victims, knows what it’s like to share a vulnerable story of sexual abuse and to have that story questioned. She is herself a survivor of abuse within the Roman Catholic Church. From 1986 to 1988, she was abused by a choir director at Santa Ana’s Mater Dei High School, in the Roman Catholic Diocese of Orange. By the time the abuse ended, she said, the teacher had left her pregnant and with a sexually transmitted disease. She was only 17.

It wasn’t until 2005 that Casteix and other survivors in her area finally had access to documents the diocese had kept about sexual abusers in its midst. The documents, obtained as part of a $100 million settlement between the diocese and 90 alleged abuse victims, showed how officials had protected priests and teachers who molested children.

It was proof of what she’d been saying all along ― that church officials knew about abuse taking place in the diocese and didn’t do enough to protect victims.

Given this history with the church, it’s not hard to understand why Casteix’s voice sharpened as she spoke to HuffPost about Francis’ attack on abuse victims in Chile.

“Every abuser says to his victim: You have no proof. No one is going to believe you,” said Castiex, now an activist with Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests (SNAP). “What Pope Francis did was put himself in the abuser’s seat, in the power position.”

“What he’s doing is revictimizing every single child victim and putting himself in the abuser’s shoes.”

Unabashed Support For A Controversial Bishop

Francis’ comments about Barros came at the end of a papal trip to Chile that was already fraught with tensions.

Chilean abuse victims and their allies have been upset about the pope’s continued defense of Barros. Several victims claim that Barros covered up and, in some instances, observed abuse carried out by his mentor, Rev. Fernando Karadima.

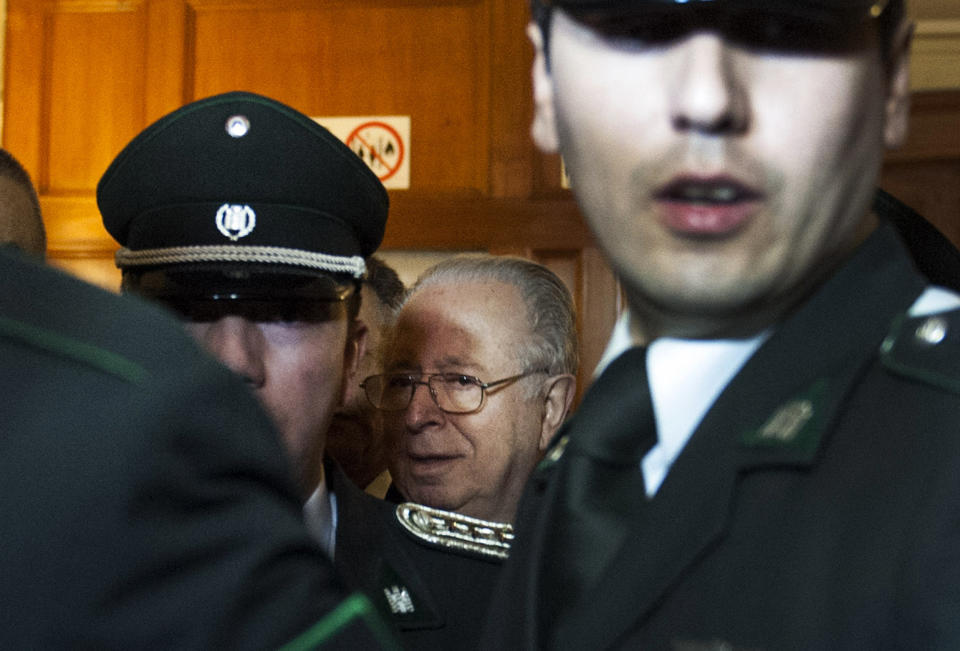

The Vatican convicted Karadima of abusing teenage boys in 2011 and sent him to live a cloistered life of “penitence and prayer” in a Chilean convent. A judge found the allegations against Karadima to be “truthful and reliable” but dismissed a criminal case against the priest because the statute of limitations had expired.

Barros denied having any knowledge of Karadima’s abusive actions ― and it appears that Francis still believes him.

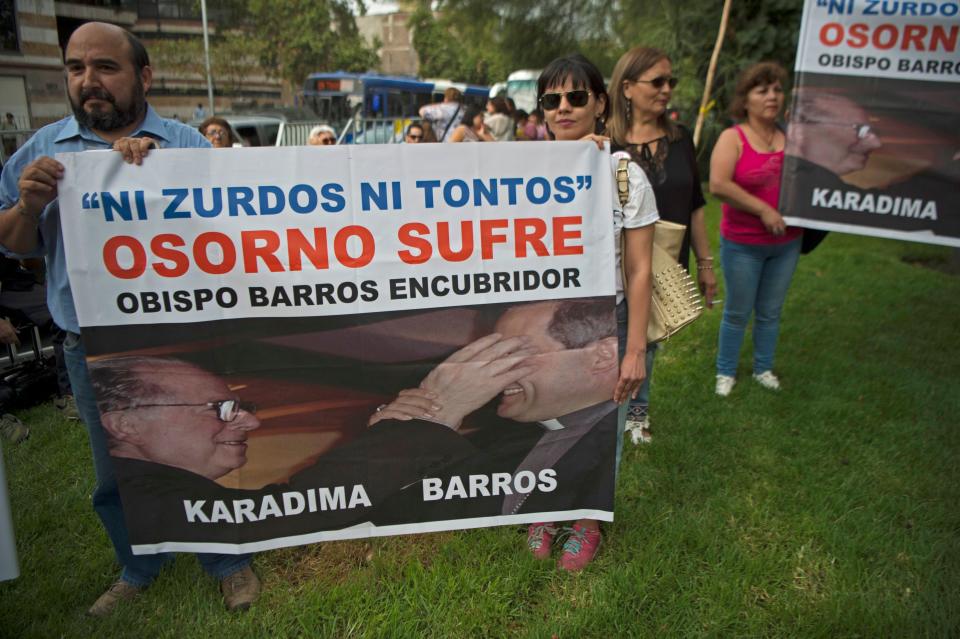

In 2015, the pope appointed Barros as bishop of Osorno, in southern Chile. Politicians and even some church leaders in the country vocally opposed the move and called for Barros to resign.

That same year, Francis was captured on video telling a group of tourists at Vatican City that people in Osorno who protested Barros’ appointment were “dumb” and “judging a bishop without any proof.”

Francis’ trip to Chile this week was marred by street protests and the burning of nearly a dozen churches as people voiced frustration with how the church is handling the clergy sex abuse scandal.

On Tuesday, Francis expressed “pain and shame” over the abuse scandal and begged for victims’ forgiveness. He met and reportedly wept with Chilean survivors of abuse, The Associated Press reported.

But he has also continued to show support for Barros. The New York Times reported that the bishop participated in the pope’s ceremonies in the cities of Santiago, Iquique and Temuco.

Barros told reporters that the Pope offered him “words of support and affection” during the visit.

Words Versus Action On Preventing Sexual Abuse

In the past, Francis has shown signs that he’s willing and ready to take serious steps to confront the problem of sexual abuse in the church. Still, some victims’ advocates are worried that the Vatican is not moving quickly to keep kids safe.

In December 2013, victims’ groups rejoiced when Francis decided to assemble a Vatican committee dedicated solely to fighting child sex abuse in the church. The group, the Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors, initially included two survivors of clergy sex abuse.

In 2017, one of those survivors, Irish activist Marie Collins, announced that she was stepping down out of frustration with Vatican bureaucracy. In an opinion piece for the National Catholic Reporter, Collins wrote about facing a number of stumbling blocks, including a lack of resources and the resistance of some in the Vatican Curia toward implementing the commission’s recommendations.

The last straw for her was the refusal of a group at the Vatican to ensure that all letters from victims received a response.

“I find it impossible to listen to public statements about the deep concern in the church for the care of those whose lives have been blighted by abuse, yet to watch privately as a congregation in the Vatican refuses to even acknowledge their letters!” Collins wrote last March. “It is a reflection of how this whole abuse crisis in the Church has been handled: with fine words in public and contrary actions behind closed doors.”

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

In December, all of the commission members’ terms formally expired and the initiative’s future is unclear.

Secular groups have also delved into the problem of sexual abuse in the Catholic church. In December, the Australian government concluded an extensive, multi-year inquiry into sexual abuse of children in the country. The commission’s final report found that 59 percent of the more than 8,000 survivors interviewed said they were sexually abused in an institution managed by a religious organization. About 62 percent of that group said that the institution was managed by the Catholic Church.

The commission came up with a number of recommendations for the church. It urged the church to end the secrecy of the confessional when it prevents or discourages compliance with mandatory reporting laws. The commission also asked the church to rethink the requirement of priestly celibacy, which, while not a direct cause, elevated the risk of abuse.

Melbourne’s archbishop has dismissed both of those recommendations, since they involve changes to longstanding church tradition.

But Kieran Tapsell, a retired civil lawyer who submitted a paper on canon law to the commission, believes there are many other recommendations the commission made that could be put into practice ― such as ensuring there’s no statute of limitations for canonical trials and requiring Vatican congregations and courts to publish reasons for their disciplinary decisions.

″[These] recommendations had more to do with church law and practice, and could be more easily implemented, if church leadership is willing to take up this challenge,” Tapsell wrote in an analysis for the National Catholic Reporter.

But, as demonstrated in Chile, much of that change starts with the pope.

The president of the Chilean bishops’ conference, Monsignor Santiago Silva, told The New York Times on Friday that it would continue to support Barros ― trusting in Francis’ opinion of the bishop.

“The pope told us what he wants, and he wants Monsignor Barros to continue,” Silva said.

Backlash In Chile And Across The Globe

In Chile and around the world, Francis’ remarks in defense of Barros have caused outrage among survivors of clergy abuse.

Juan Carlos Cruz, one of Karadima’s most vocal victims, was particularly unnerved by Francis’ demand for “proof” that Barros had been complicit in the abuse.

“As if I could have taken a selfie or photo while Karadima abused me and others with Juan Barros standing next to him watching everything,” Cruz wrote on Twitter, according to a BBC translation.

“These people are absolutely crazy, and [the pope] is talking about reparation to the victims. Nothing has changed, and his plea for forgiveness is empty.”

Patrick Noaker, a lawyer who has represented dozens survivors of sexual abuse in Minnesota, said that Cruz’s testimony appears to him to be extremely powerful. That’s because when it comes to child sexual abuse, there is rarely evidence outside the testimony of the victim.

Francis’ defense of Barros is a reminder to Noaker that bishops are “the princes of the Catholic church, and they are protected at all cost.”

“The statement by the pope reveals a hard-liner position that he will protect bishops over children,” he told HuffPost in an email. “This will discourage survivors of sexual abuse from reporting their abuse because they will not have photographs or other evidence of the abuse outside of their testimony.”

Other advocates for abuse survivors have the same fear that victims will be afraid to come forward with their stories. Anne Barrett Doyle, co-director of the online database BishopAccountability.org, called Francis’ attack on the Chilean sex abuse survivors a “stunning setback.”

“The burden of proof here rests with the Church, not with victims ― and especially not with victims whose veracity already has been affirmed,” Doyle said in a statement. “Exhaustive investigations by both church and civil authorities proved the allegations of Juan Carlos Cruz [and others] in regards to Karadima. A reasonable person would consider that they are telling the truth about Barros also.”

“Who knows how many victims now will decide to stay hidden, for fear they too will be attacked as slanderers?” she added.

David Greenwood, a volunteer lawyer with the British advocacy group Ministry and Clergy Sexual Abuse Survivors, echoed Doyle and Noaker’s concerns.

“For the Pope to be deliberately confrontational and challenging in this way will prevent survivors coming forward to share their ordeals,” Greenwood told HuffPost in an email.

The church’s handling of the abuse scandal in Chile has disillusioned many of the country’s Catholics. A survey by the regional polling firm Latinobarometro found that only 42 percent of Chilean Catholics approved of the job Francis is doing, compared with an average of 68 percent for 18 other Central and South American countries.

Casteix told HuffPost that, in her view, there’s nothing the pope can do now to prove that his apologies to sex abuse victims are meaningful.

“It is as if Pope Francis took a trip to Chile, apologized for abuse, prayed for healing, asked for forgiveness, and then got on his plane and said, ‘Just kidding.’”

Also on HuffPost

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.