'What is clean water worth?' Long-awaited Montgomery Drain project nears $50M, completion

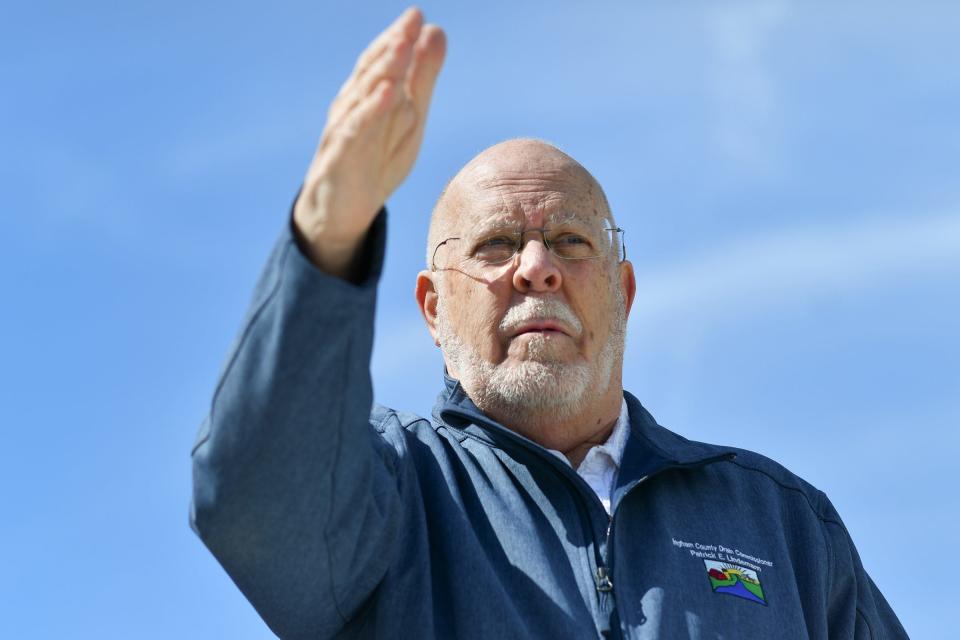

LANSING — Pat Lindemann strolled past a series of fountains, "bio ditches," catch basins and other structures nestled on a slice of property east of the Frandor Shopping Center, occasionally stopping to note where sculptures will stand and how things will work “when we turn the water on.”

“You can spend all day out here and not see everything,” the Ingham County drain commissioner said on a recent March afternoon, pausing in the northern end of Ranney Park where an expanded sledding hill and a waterfall now stand. "School teachers can bring busloads of kids here. It will be a learning tool for non-source-point pollution."

The source of Lindemann's excitement is the Montgomery Drain project, a once-controversial, often-delayed and hugely expensive stormwater management and pollution control system. It collects runoff from a one-square-mile area stretching from neighborhoods north of Saginaw Street along U.S. 127 to south of Michigan Avenue, including the sprawling Frandor Shopping Center and the former Red Cedar Golf Course.

Construction began in 2019, shortly before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, and if everything goes as planned, it will be finished by late July. Lindemann now estimates the total bill will be $45 million to $50 million − $15 million to $20 million higher than expected as recently as seven years ago.

The development features 2½ miles of paved walking and biking trails, numerous holding ponds, rain gardens, fountains, weirs, waterfalls and other infrastructure that comprise the "treatment train," a system designed to clean stormwater before it ends up in the Red Cedar River. Eventually, ecology-themed art pieces, interpretive signs and numerous trees and wildflowers will adorn the site.

Lindemann said the overhauled drain is capable of storing all of the rainfall from a two-year, 24-hour storm − about 2.5 inches worth − and will eliminate 90% to 95% of the pollution the drain historically has sent into the Red Cedar River. That figure is somewhere around 50,000 to 75,000 pounds of pollutants a year, making the old drain the biggest polluter among the river's 236 inlets, he said.

In the new system, runoff that collects in retention ponds near the river gets pumped back uphill and sent back down through a series of waterfalls, weirs and other fixtures made of concrete, limestone blocks, rocks, gravel, sand and vegetation. Those features are designed to purify the water by filtering and oxygenating it.

All told, there will be about 1,500 trees and 150,000 to 200,000 wildflowers, Lindemann said.

'What is clean water worth?'

The project, first conceptualized nearly 30 years ago, has been beset by lawsuits, cost increases and pandemic-related delays. The lawsuits were eventually dismissed. Cost estimates have grown from around $30 million in 2016 to about $35 million in 2020 to up to $50 million this year. In early 2021, the drain was expected to be finished by the end of that year. But the completion date was later pushed back to late 2022, then to late 2023.

Lindemann said pandemic-related factors account for about $14 million to $18 million of the total cost of the project. For example, the resin used to make PVC pipe comes from China and "nearly dried up" during the pandemic, and contractors also had to deal with soaring labor costs, he said.

The massive drain project involved five or six main contractors and another 10 or so subcontractors and was broken into 14 divisions that operated separately, Lindemann said.

"We did everything we could to save money, and then COVID came along and blew that right out of the water," Lindemann said. "We tried to rebid a couple of divisions, and they all came in higher."

The Lansing Regional Chamber of Commerce and Lansing Mayor Andy Schor called for pausing the project or scaling it back because of the financial impact of the pandemic, but Lindemann persisted, saying any delay would end up costing more in the long run.

"You can't just stop in the middle of the stream and just come back to it," Lindemann said in early 2020, noting the drain infrastructure was "totally dilapidated" and needed a complete overhaul.

His perspective hasn't changed. The longer you wait to fix the drain, the more it will cost, he said. And if you stopped the project, you'd have to pay start-up costs on top of the COVID-related costs, he said.

Lindemann also maintained the revamped drain adds economic value, working in synergy with the new development along Michigan Avenue. That includes the massive, mixed-use Red Cedar development along a main corridor connecting Lansing and East Lansing.

"All of that leads to more tax revenue for the city, more ability to manage the drain cost, and it puts in place a methodology that all of those elements put together leads to a cleaner river," he said.

During his walking tour of the project on March 11, he posed the question, "What is clean water worth?"

Lindemann said the drain work was done in concert with the 35-acre Red Cedar development on the site of the former golf course south of Michigan Avenue and the ongoing rebuild of U.S. 127 at the western edge of the drain area.

As part of their agreement with the city, the Red Cedar developers built the Jack and Susan Davis Amphitheater at the southern end of the drain project and donated it to the city's parks department, Lindemann said. Developers also contributed to the project in other ways, including by building to certain standards in coordination with the city and drain commission, he said.

The drain project officially got off and running in 2014, after the city of Lansing and Ingham County petitioned for improvements and a drainage board determined them necessary. The drain had failing pipes and too little capacity, and it was pouring a large quantity of polluted stormwater into the Red Cedar, Lindemann said.

He settled on a "targeted low-impact design" over six other alternatives, including building a new wastewater treatment plant.

The public costs are being shared according to a formula set years ago. The city of Lansing has the largest share, at about 64%, followed by Lansing Township at 14% and the Michigan Department of Transportation at 9.9% . East Lansing's share is 7.2%, while Ingham County is responsible for 4.6%.

Each municipality determined how it would pay its share.

Lansing decided to split its cost equally between an assessment on property owners who live in the area served by the drain and a 0.26-mill property tax levied on all property owners in the city. East Lansing decided to pay its share from its general fund. Lansing Township officials have not discussed the project with the State Journal, but Lindemann said it is paying its share with a township-wide special assessment.

If the project ends up costing $50 million, Lansing's share would be about $32 million, followed by $7 million for Lansing Township, $4.9 million for MDOT, $3.6 million for East Lansing and $2.3 million for the county. The county was able to use some federal grant money for the project.

The municipalities had no choice but to pay their share of the cost but had input into how the project was done. Lindemann coordinated the drain work with sewer separation work done by Lansing and East Lansing.

"No one wants to pay for it, but we all want to benefit from it," said Scott House, East Lansing's public works director. House described the nearly finished drain as "pretty impressive" and said it will help clean up the river.

Said Lindemann: "I used the advice of everybody, and we decided on a method. It's hard to spend that much money, but when you have something that's wrong, you have to fix it. It could cost billions to clean up the river."

Using art to teach people about ecology

The nearly finished project looks a lot like what Lindemann described when he publicly shared his vision for it in 2016.

The system is operable, but Lindemann doesn't expect to turn on the pumps until late April or early May.

"We still have sidewalks to put in, some piping to do in various areas and some highway pipes to be fixed so they are connected properly," he said. "There is a lot of vegetation to plant yet. We have a group coming out to plant wildflower seed. There is capping for the fountains that have to go in, weirs that have to be made and installed."

The miles of paths winding through the development also are access roads for maintenance crews and were built to support trucks, he said. The access roads needed to be there, anyway, so Lindemann decided to make them double as hiking and biking paths open to the public.

The expanded sledding hill in Ranney Park was built with soils excavated for the drain project, a measure that saved nearly $3 million, he said.

Lindemann's nonprofit, Art in the Wild, is raising money to help pay for the sculptures, which include an abstract eagle figure dubbed the "Wind Lord," which will sit atop a fountain in the median of Michigan Avenue. The sculpture will be owned by the city of Lansing, he said. The plan is that artists will obtain grants to build their pieces.

The total monetary value of the art component of the project was unclear.

"The mission statement (of Art in the Wild) is, 'we promote clean water through art,'" Lindemann said.

"We're using art to reach people about clean water," he said. "We can avoid these high prices of cleaning water if we don't pollute it. The only way to do that is to change people's attitudes about clean water and get them to live a more ecological life."

The process of cleansing runoff contaminated with rubber, road salt, oil, fertilizers and other pollutants is complex and entails more than 150 elements, Lindemann said. In essence, the configuration was designed to mimic natural processes that cleanse ground water.

"The reason there are so many waterfalls is because they add oxygen to the water," Lindemann said, noting that oxygen helps in the composting of bio pollution. Limestone helps neutralize pH, he said.

Two weirs connect the retention ponds at the southern edge of the drain to the river itself, so water can flow either way, if necessary, to help manage localized flooding, Lindemann said.

Some of the 15 or so waterfalls will be lit at night, and the walking paths also will be illuminated. Lindemann said the lights will go off at designated times to leave the area dark most of the night. That will help promote a natural ecosystem amenable to turtles, snakes, frogs and other wildlife, he said.

Spotting the drain commissioner walking in the northern part of the development on a March day, Nathaniel DuPhene of Holt walked up to ask a nagging question.

"My oldest daughter is 9 now," DuPhene said. "Is this park going to be done before I get grandkids?"

A chuckling Lindemann assured him it will be done this year.

Contact Ken Palmer at kpalmer@lsj.com. Follow him on X @KBPalm_lsj.

This article originally appeared on Lansing State Journal: Montgomery Drain project in Lansing near Frandor almost done