City officials threw me in jail to silence me. Years later, I'm still seeking justice.

Coming from a law enforcement family, I never had issues with police in my life – not even a traffic ticket. As the first Hispanic woman elected to the City Council of Castle Hills, Texas, and having lived here for 20 years, my campaign issue was fair treatment for everyone, not just the well-connected.

I was so happy when I won in 2019. Little did I know that soon after, crooked politicians and their friends would use the power of the government to violate my constitutional rights by removing me from office, and even throwing me in jail, because city officials didn’t like being criticized for doing bad work.

That's not the end of my story, however. Because of the obscure and immoral judge-created doctrine of qualified immunity, my efforts to enforce my First and 14th Amendment rights have been thwarted by excessive delays.

My story: They didn't like what I was saying.

During my campaign in 2019, I visited and spoke with residents in more than 500 households and listened to their frustrations and complaints about City Manager Ryan Rapelye.

After the election, a few people who were unhappy with the results circulated an online petition supporting Rapelye and got about 150 signatures. This upset people who had voted for me, and they began to ask us to circulate a petition to reflect their concerns.

At my first council meeting, the petition was turned in to the mayor, who didn't distribute the petition to the city secretary, as required, so copies could be made for all council members.

As the meeting was about to start, the city attorney told me I was no longer on the council because the sheriff, who had read me my oath at the council meeting, was not qualified to swear me in.

Qualified immunity: Supreme Court just doubled down on flawed qualified immunity rule. Why that matters.

No one had voiced a problem at the time of the swearing-in ceremony, which was attended by the city attorney, the mayor and the entire City Council. A previous sheriff had also sworn in other council members with no issue.

It was clear I was being harassed for doing my job on the council to report on the community's frustrations with the city manager, who was obviously well-connected.

The harassment continued, and worsened.

In the July-August city newsletter, “The Castle Hills Reporter,” which is mailed to all residents and businesses in the city, Councilman Skip McCormick wrote an article describing how a City Council member could be removed from office. He said they could be convicted of a crime or by filing of a lawsuit against the council member, which sets up a jury trial – a blueprint for what ended up happening to me.

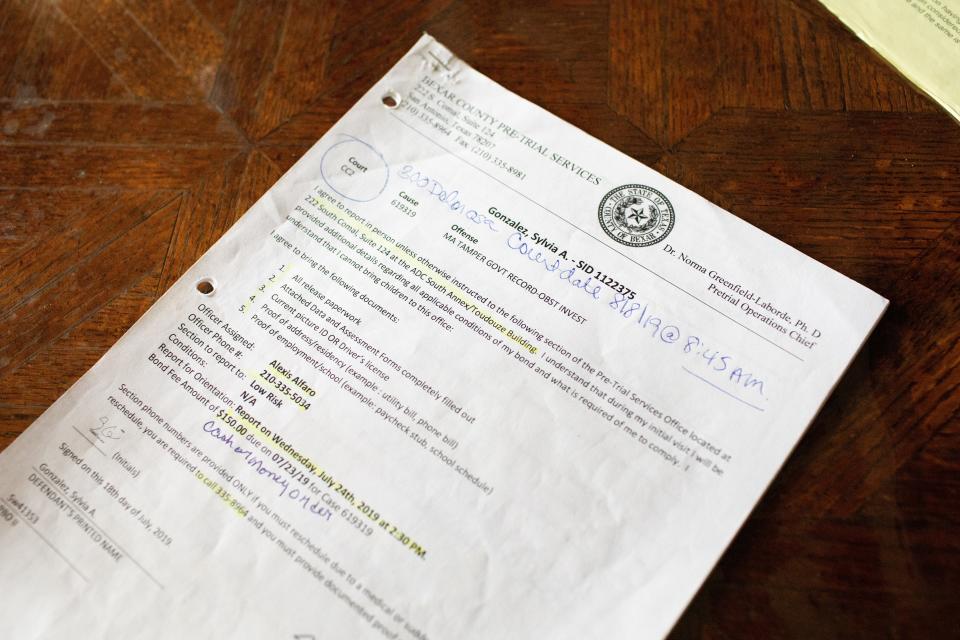

With the help of friends, I hired an attorney and filed with the county court to get my City Council seat back. On July 18, a neighbor called early in the morning and told my husband that the sheriff's deputies were about to serve me with an arrest warrant. After turning myself in at the detention center (where I spent the day in handcuffs), I discovered that the crime I was accused of – by the mayor – was "tampering with governmental record."

Qualified immunity: He was asleep in his car. Police woke him up and created a reason to kill him.

The elaborate setup by cronies of the city manager was all over the news. I did nothing criminal, and the district attorney dismissed the charge that had been brought against me.

I had to spend my own money to locate and hire a criminal defense attorney. Meanwhile, a Castle Hills police officer visited the homes of the people who had signed the petition.

I dropped the civil case because I couldn't afford it. My attorney sued for compensation of all the money I had to spend, and to be paid back for what they put me through. The matter was dismissed Sept. 29 by the 4th Court of Appeals.

USA TODAY Opinion Series: Faces, victims, issues of qualified immunity

The Institute for Justice agreed to file a federal lawsuit against the city of Castle Hills and had a hearing before U.S. District Judge David Alan Ezra. The individual defendants requested that the suit be dismissed on the basis of qualified immunity, a doctrine that was intended to keep police and other government officials from being punished for reasonable acts while on the job, but which has ended up precluding plaintiffs from money damages to which they are legally entitled.

Judge Ezra denied the individual defendants qualified immunity, allowing my case to move forward. The city appealed this ruling to the U.S. Court of Appeals in New Orleans, where we will meet Wednesday.

The mayor and his allies broke the law, violated the U.S. Constitution, ignored the people who voted for me and nowpleadqualified immunity to avoid responsibility. My civil rights were denied because I did not receive equal treatment under the law and my right to freedom of speech was violated. I was arrested and thrown in jail because the city officials who didn’t like the criticism against them decided their best move was to silence me. The right to disagree with the government is the very essence of our democracy, and I was punished for exercising my right to do so.

Despite the extreme stress, I believe it is my duty to stand up to try to ensure that others are not silenced the way I was.

Qualified immunity must end. We must strive to hold government accountable, no matter how big or how small, and no matter whose rights have been violated.

Sylvia Gonzalez is a former city councilwoman of Castle Hills, Texas. She was the city's first Hispanic councilwoman and is the daughter of a retired police officer.

This column is part of a series by the USA TODAY Opinion team examining the issue of qualified immunity. The project is made possible in part by a grant from Stand Together. Stand Together does not provide editorial input.

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Texas put me in jail to keep me quiet. Qualified immunity is immoral.