City Council's 2-minute speaking limit fails judicial scrutiny — and the public | Grumet

Roy Waley has talked about water issues at Austin City Council meetings for more than three decades, becoming such a fixture at City Hall that “I feel like I should get my mail delivered there,” the Austin Sierra Club advocate joked last week.

The wisecrack drew chuckles Tuesday afternoon in a 10th floor courtroom in the Travis County civil courthouse. But Waley takes his time seriously. He wants the council to take public speakers seriously, too: Hear them out, even if it makes meetings run longer.

“Democracy can be messy and time-consuming,” Waley testified at the court hearing.

At issue is the City Council’s somewhat recent rule limiting each speaker to two minutes, no matter how many topics they want to address on a consent agenda that usually teems with dozens of complex items — from multimillion-dollar contracts to legal settlements to the city’s latest drought and water conservation plans. The council typically passes the entire consent agenda with one sweeping vote, then moves on to other matters scheduled for public hearings.

The larger question is how much of a voice the public should have in public meetings. Clearly, community input is integral to good government. But how do you set ground rules that respect everyone’s time?

This issue will find its way back to the council, as two judges within the past month have found the council’s two-minute rule violates the Texas Open Meetings Act.

State law says a governing body may “limit the total amount of time that a member of the public may address the body on a given item.” But it says nothing about setting a total time limit for all items a speaker wishes to address.

District Judge Daniella Deseta Lyttle’s order on Tuesday, which extends the temporary restraining order that District Judge Madeleine Connor issued April 17, requires the council to give each speaker three minutes per agenda item until a final court hearing on the matter July 1.

Neither the old rule nor the court order limits the total number of people who may speak. In fact, a 2019 addition to the Texas Open Meetings Act says a governing body must provide an opportunity for everyone who wants to speak about an item on the agenda.

The lawsuit was brought last month by the Save Our Springs Alliance, an organization rooted in Austin's high-water mark of civic activism, the 1990 all-night meeting where more than 150 speakers persuaded the council to reject a massive development that would have imperiled Barton Creek and Barton Springs.

At Tuesday’s court hearing about the two-minute rule, attorney Bill Bunch, executive director of the Save Our Springs Alliance, invoked James Madison: A democracy without information “is but a prologue to a farce or a tragedy; or, perhaps, both.”

“I think that's what we're seeing here, with the council cutting off the intelligent and impassioned input of their community,” Bunch said.

Why did Austin set new speaker time limits?

For years, Austin City Council meetings routinely ran well into the night. At Tuesday’s court hearing, Assistant City Attorney Brandon Mickle showed that nine council meetings in 2019 — nearly half of the regularly scheduled meetings that year — went past 9 p.m. Two ran into the early morning hours (ending at 2:20 a.m. and 4:17 a.m.), making public participation an endurance challenge.

At that time, speakers typically got three minutes to speak on each item.

“This speaks to the council’s need to balance speaker time and (ensure) government does not grind to a halt,” Mickle told the court.

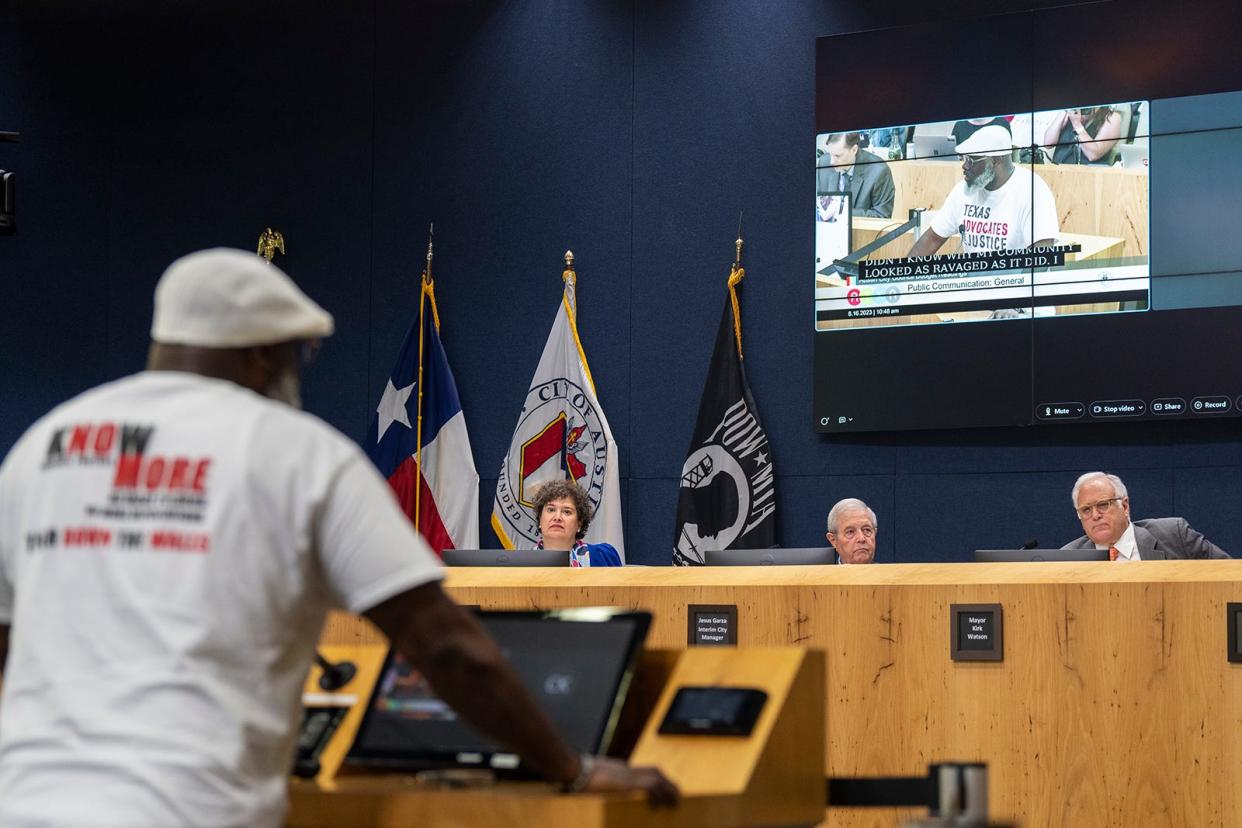

After Mayor Kirk Watson took office, he posted the two-minute rule on the council message board in March 2023, providing that fixed amount of time no matter how many consent agenda items a speaker wanted to address. Speakers also get two minutes for each item that’s scheduled for a public hearing.

(At the risk of getting into the weeds, I should also note this rule was not enacted by a council-approved ordinance, as the city charter requires, which is another reason both judges have found fault with the city’s policy.)

The impact of the new time limit was noticeable: Over the next 18 meetings, only three went past 5 p.m., and only one went past 7 p.m.

Watson runs a tighter ship than his predecessor, and I applaud him for starting at 10 a.m. sharp (previous council meetings often began 15-30 minutes late).

But in some ways the pendulum has swung too far, from rambling late-night meetings to two-minute speaking drills for advocates trying to cover a range of important items. Austin still needs to find a happy medium.

Public input is key to the public's business

I think Austin can get there. Even with the judge’s temporary order requiring three minutes per speaker per consent agenda item, the council meeting this past Thursday ended at 7:04 p.m. People weren’t there all night, even with a bunch of speakers lined up for a couple of controversial issues, such as the council’s resolution on gender-affirming care.

Waley, who had up to 12 minutes to speak on four items, covered his points in less than half that time. Other advocates similarly used a fraction of their allotted time.

Not only do members of the public deserve to have their voices heard, but they can offer valuable insights that can help council members make better decisions. And while a reasonable time limit is needed to keep the meeting moving, public comment should not be the default place to squeeze when council meetings run too long.

The city can make other adjustments: Don’t put too many items on one agenda. Schedule an additional council meeting if necessary. Use committee meetings and work sessions to resolve questions.

Yes, council members and Austinites need to respect one another’s time. Most of all, they need to recognize they’re all there to handle the public’s business. Hearing from members of the public is essential to that mission — not interfering with it.

Grumet is the Statesman’s Metro columnist. Her column, ATX in Context, contains her opinions. Share yours via email at bgrumet@statesman.com or on X at @bgrumet. Find her previous work at statesman.com/opinion/columns.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Court finds fault with Austin City Council's 2-minute speaking limit