Chuck Grassley helped Trump redefine the judiciary. Now he will fend off demands to see president’s tax returns

WASHINGTON — She’s a bartender from the Bronx. He is a farmer from Iowa. She is 29. He is 85. She routinely wins Twitter by trolling Republicans. He recently posted a photo of a pork chop on Instagram. She is new to Washington, having won her first election to public office in the November midterms. He has been on Capitol Hill since the Ford administration.

This is not a love story. It is instead a story of two chambers, the House of Representatives and the Senate, that are diverging drastically, not only in political power but demographic composition. The bartender from the Bronx is, of course, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who represents a remarkably diverse incoming House class. Having taken over the lower chamber of Congress, the incoming Democrats are proposing an unapologetically progressive program that includes everything from a Green New Deal to impeaching “the motherfucker,” as newcomer Rep. Rashida Tlaib, D-Mich, said of President Trump on her very first day in office.

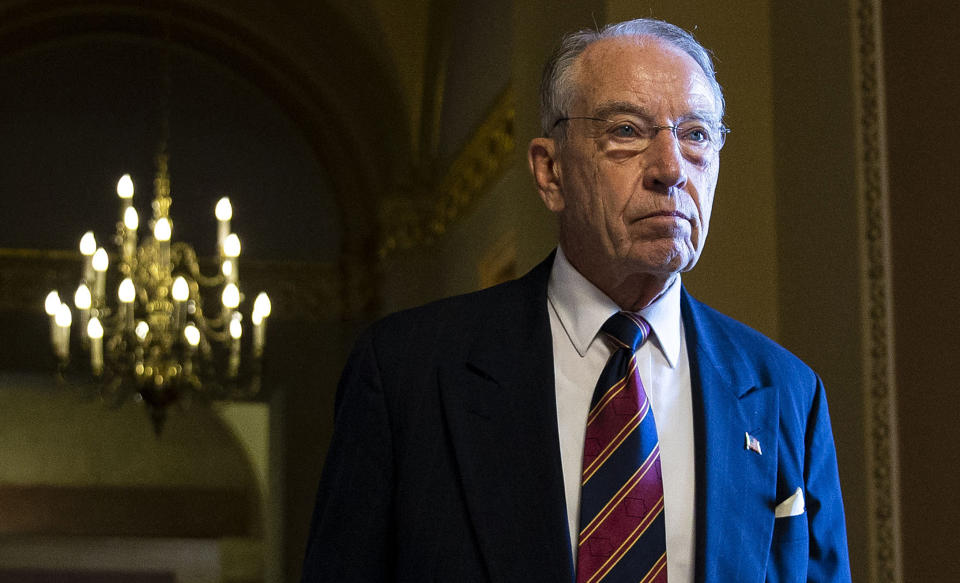

The farmer from Iowa is Sen. Chuck Grassley, who represents Congress not as some would like it to be but how it has long been. Much as Ocasio-Cortez and her peers may want to get rid of Trump — and they are not shy about wanting precisely that — they will have to contend first with the Senate’s second oldest member.

Sitting in his Senate office on the day before the 116th Congress began, Grassley sipped from a glass of what appeared to be apple juice as he looked back with Yahoo News on two years of full Republican control of Congress. In doing so, he reminded of how he had become one of Trump’s most reliable and effective allies on Capitol Hill.

Fresh from confirming a record number of conservative judges as chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, Grassley is now moving to head the nearly-as-powerful Senate Finance Committee, where he will fight off Democratic attempts to force the release of Trump’s tax returns. Along with colleagues like Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., and Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, he forms a seasoned Republican firewall against the young Democratic firebrands.

Grassley’s longevity, as well as a loyalty to the Republican Party, have not gone unnoticed. On the same day that Tlaib and Ocasio-Cortes became new members of Congress, Grassley’s own influence was underscored when he was made president pro tempore of the Senate, a position that puts him “three heartbeats away from the presidency,” as he noted in a Des Moines Register op-ed.

Grassley embodies a paradox that has become increasingly rare in Washington: a party loyalist whose loyalty cannot be taken for granted. Democrats hoping that his Midwestern decency might lead him to buck Trump have been disappointed. Republicans who expected him to unquestioningly follow party leaders have sometimes found themselves surprised.

Late last year, for example, Grassley defied Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell in taking up criminal justice reform instead of confirming more judges, as McConnell wanted him to do. Not only did that legislation, known as the First Step Act, mark the most significant rethinking of sentencing guidelines and rehabilitation policies since the early 1990s, it received an astonishing 87 votes in the Senate. One of those votes belonged to McConnell, who for once found himself following Grassley’s lead.

McConnell’s rare reversal was a tacit concession of just how much Grassley has done for him, and for Trump. He is remarkably easy to underestimate, which works inevitably to his advantage. That has been the case for nearly the entirety of his career. “Iowa’s Grassley Gets Last Laugh on His Detractors,” went the headline of a 1985 article ahead of his first Senate reelection campaign. Once confident that they were going to retake his seat, Democrats were less sure he was “a one-term rube who had the dumb luck to run for the Senate in the Reagan landslide year of 1980.” He would in fact win the 1986 reelection, and the five Senate contests after that.

The slights have never quite ceased. Last summer, during the fight over Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination to the Supreme Court, lawyer Michael Avenatti — who represented one of the women accusing Kavanaugh of sexual assault — declared on Twitter that Grassley was “far too stupid to lead” one of the most influential committees in Congress. If derision of that kind bothers Grassley, he does not show it in public. Not only did he win the Kavanaugh fight, but he worked with White House counsel Don McGahn and McConnell to confirm 84 other judges to the federal bench, including Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court along with Kavanaugh.

Trump may never get his border wall with Mexico, but the young, conservative judges he and Grassley have successfully confirmed could form a resilient barrier against the progressive policies of legislators like Ocasio-Cortez for a generation.

But ask Grassley about his greatest accomplishment, and he will bring up the judges only after the First Step Act. Touted as a rare bipartisan success, First Step is for Grassley less evidence of political comity than of political process properly executed, Congress not living up to some mythical standards but Congress working exactly as it should.

“Heavens,” he says, Midwestern accent growing strong. “Just think of the steps we had to take.”

McConnell had, after all, prevented a similar measure from coming to the Senate floor in 2016. And after the presidential election, the effort seemed dead for sure, given Trump’s forceful, if vague, law-and-order platform. It was during the congressional lame duck session following the election that Grassley ran into Dick Durbin, D-Ill., on the Senate floor and told him he wanted another try at the bill.

Grassley thought — correctly, it would turn out — that they would have an ally in the president’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, someone who could eventually override and even overturn Trump’s own impulse for toughness over compassion. For two years, Grassley and Durbin each labored to placate his own caucus while making sure that the other side was not alienated by either too much reform or too little.

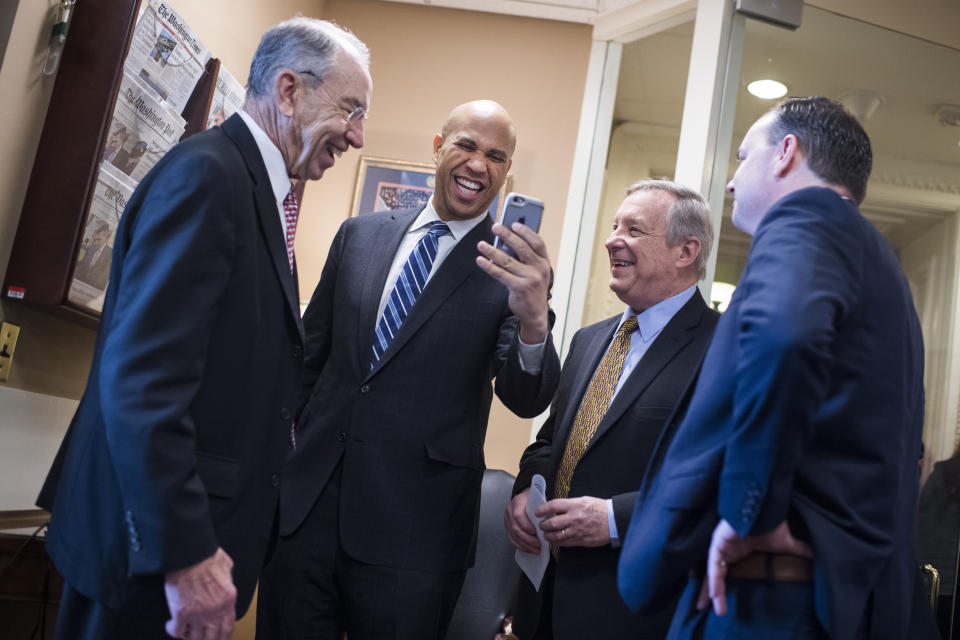

The final obstacle was McConnell. In a phone call with the Senate majority leader, Grassley made the case that the 116th Congress would see plenty of judges through with Graham as the new chairman of the Judiciary Committee, but that criminal justice reform was more urgent. McConnell relented, his choice made easier by Sen. Jeff Flake’s declaration that he would hold up all judicial nominees until protections for the investigation into Russian electoral interference were put into place. An already iconic photograph from the bill’s passage shows Grassley embracing Sen. Cory Booker, the progressive Democrat from New Jersey who has as much in common with Grassley as the Atlantic City Expressway does with an unpaved country road.

First Step was not an outlier, Grassley argues. His staff is eager to point out that during his time as chairman, 61 bipartisan bills advanced to the full Senate, and 34 of those became law. A four-page handout listing his Senate Judiciary accomplishments begins with judicial nominations, but devotes far more space to bipartisan legislative accomplishments.

Yet the judges are inarguably what Grassley’s turn as Senate Judiciary chairman will be remembered for. More circuit court judges — 30 in all — have been confirmed by Grassley and Trump than by any other president during his first two years in office. There have been 53 district court judges, too, in addition to the two successful Supreme Court picks.

“The White House was all set to move quickly on judges,” Grassley says, praising the Trump administration for “getting nominees up here from the White House much faster than they did under Obama or under George W. Bush.”

He does not mention that President Barack Obama’s nominees were effectively stalled by McConnell, a strategy that gave Trump openings on the federal bench to fill.

Democrats on the Senate Judiciary Committee found Grassley to have an “issue by issue” approach, as a senior aide to one Democrat on the committee put it. Aside from working with Durbin and Booker on the First Step Act, he advanced legislation with the committee’s ranking Democrat, Sen. Dianne Feinstein of California, that would protect young athletes from predators like Larry Nassar, the disgraced former doctor for USA Gymnastics. Trump eventually signed that bill into law.

Democrats knew that Grassley was going to advance Trump’s judges. What they won’t forgive him is the manner in which he did so. “After decades of putting himself out to be bipartisan guy, he was willing to destroy every norm we have in the committee for how we vet judicial nominees,” said the Democratic aide, who requested anonymity in order to speak frankly. “Anything McConnell asked him to do to get judges through, he would do it.”

Grassley’s adversaries charge that his decision to advance circuit court nominees without blue slips — endorsements from home state senators, customarily needed for a judicial nominee to proceed — was a gross abrogation of the congressional norms he supposedly reveres. Grassley also held hearings in panels that often divided time between two judges, limiting the ability to question each one. And he scheduled one hearing during a Senate recess, which led to Democratic howls of outrage. At times during the Kavanaugh hearings, Grassley seemed genuinely pained by Democrats’ appeals to precedent. Yet he ultimately cast those appeals aside, earning fulsome praise from Trump.

“Grassley has been a wrecking ball when it comes to rules and norms of judicial confirmations,” says Nan Aron of the Alliance for Justice, a group that advocates for a more liberal judiciary. “He has dispensed with Senate advice and consent responsibilities.”

This argument confounds Grassley, who like many Republicans sees Democrats resorting to high-toned rhetoric about the sanctity of institutions because it suits their political ends. “I’ve been listening too many years both under Republican and Democrat presidents that we aren’t doing enough to keep the judicial branch well supplied with qualified people. So I was trying to meet that,” Grassley says, moving to the edge of his chair as he grows animated in defense of his record.

“Nobody can raise the issue of not enough oversight,” he argues, “except something that maybe crops up at the last minute.”

There were more than a few such last-minute surprises among the judges sent by the White House to Capitol Hill. Matthew S. Petersen of the Federal Election Commission admitted under questioning from Sen. John Kennedy, R-La., that he had never tried a case in a brutally uncomfortable four-minute exchange that became an unlikely social media sensation. Brett Talley, a Harvard Law graduate, was rated “not qualified” by the American Bar Association: He had written several horror novels, but had also never tried a case. Jeff Mateer had branded transgender youth instruments of “Satan’s plan” while also condemning same-sex marriage. All three withdrew.

The senior Democratic staffer held out some hope for working with Graham, despite his performance at the Kavanaugh hearings. Graham’s proximity to Trump, the staffer speculated, could give him the latitude to tell new White House counsel Pat Cipollone to make sure that the judicial nominees sent to Capitol Hill during the 116th Congress make for fewer viral videos than their predecessors in the 115th.

One of those picks could be a third seat on the Supreme Court.

Recent concerns over the health of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg have some fearing that Trump could soon have that chance. If he does, Grassley thinks the White House should stick to the Kavanaugh playbook. “I would advise the president to keep by his campaign promise” to nominate judges from a list provided by the Heritage Foundation, Grassley says. “I think he’d be in worse trouble if he tried to pick someone who is not on that list.”

A ferocious opposition to a third partisan pick to the high court does not trouble him. “They have realized that they went overboard in trying to defeat Kavanaugh,” Grassley says of his Democratic colleagues. “If we have another Supreme Court vacancy, I don’t think they’re going to act in the same terms.”

Now, as chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, Grassley is likely to remain at once reverent of the institution of Congress and loyal to the Republican Party. His vote — along with that of the committee’s Democrats — could use a 1924 law to force President Trump to release his tax returns. Grassley has no interest in doing that.

Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., asked Hatch, the committee’s outgoing chairman, to release Trump’s taxes, and he is expected to make the same request of Grassley. “Their only justification for wanting [Trump’s tax returns] is that other presidents since Nixon have done it,” Grassley says, “but what about the presidents before Nixon, where it wasn’t big deal?” Democrats do hold out hope that, on the matter of Trump’s taxes, they can appeal to Grassley’s previous interest in tax-exempt organizations.

But even as he touts his own past work with Democrats, Grassley laments how the “grassroots” in each party are shredding the very possibility of consensus. With the House turning blue in November’s midterm election, the possibility of legislative gridlock is near certain. Also certain is that the Senate will remain a safe chamber for Trump, as long as old-timers like Grassley are in charge. Plodding though he may be, he has shown a remarkable ability to advance the president’s agenda, in large part without attracting the enmity of his Democratic colleagues, who admire his resilience even as they reject his positions.

“He is the hardest working member of Congress,” says Garrett Ventry, a former Grassley staffer on the Senate Judiciary Committee. “Grassley works. Grassley delivers.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: