China wants a new world order. At the U.N., NGOs secretly paid cash to promote Beijing’s vision.

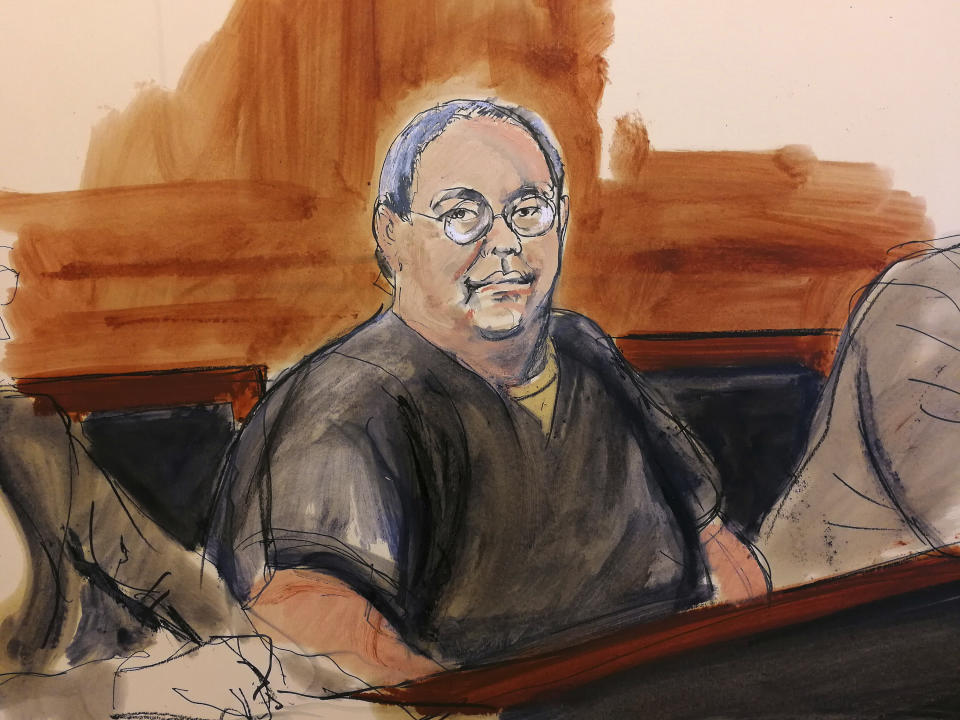

When Patrick Ho was arrested at John F. Kennedy International Airport on Nov. 18, 2017, the former Hong Kong government official made one phone call: to James B. Biden, the younger brother of the former U.S. vice president, an acquaintance whose number he had on hand.

The well-connected Hong Konger asked Biden for a lawyer.

Ho was going to need a good one. The U.S. Department of Justice was planning to indict him for using his connections at the United Nations to bribe a U.N. General Assembly president along with several African government officials.

The arrest attracted media attention because of Ho’s link to a powerful Chinese energy conglomerate, CEFC China Energy. Ho ran the energy company’s think tank, China Energy Fund Committee, an NGO affiliated with the U.N. that had offices in New York, Virginia and Hong Kong.

The former Hong Kong official was indicted on a number of foreign bribery and money-laundering charges, but the investigation surrounding Ho, his nonprofit and its parent company, and the United Nations wasn’t about just corruption. A flurry of recent court filings reveal that the government collected at least some of Ho’s communications under a warrant from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, a secret order used to monitor suspected foreign agents.

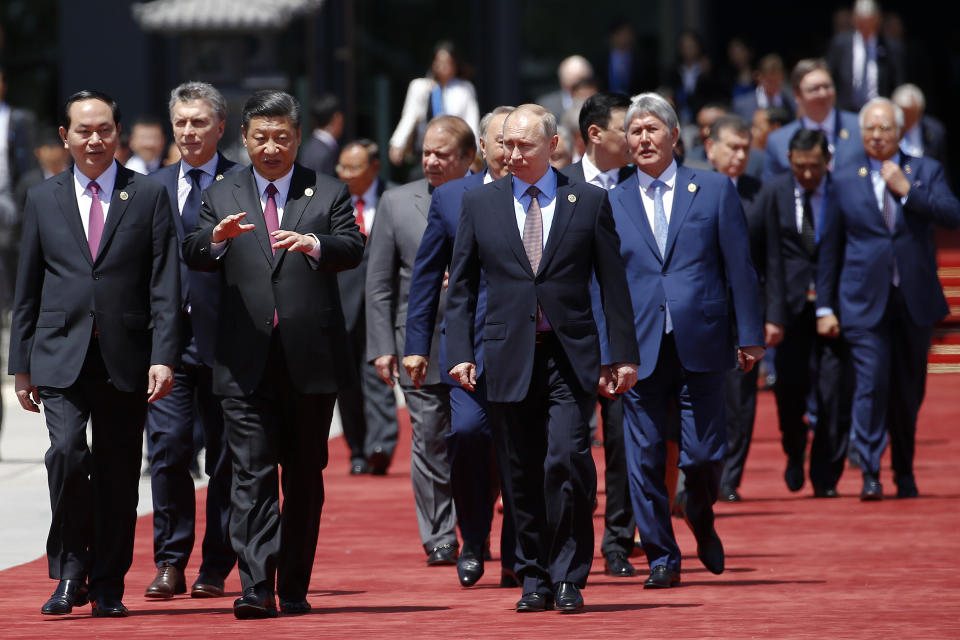

And records related to the case — including documents submitted by Ho’s own attorney — now connect Ho’s alleged payments to promotion of a major Beijing foreign policy push called the Belt and Road Initiative, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s signature venture advancing investment and infrastructure projects around the world. Belt and Road isn’t about only inking business deals; it offers a sweeping vision of a China-centric political and economic global order, one in which countries depend on China, not the West, for prosperity.

China’s influence operations have been getting high-level attention in the Trump administration, particularly as it attempts to fend off allegations of collusion with Russia. In September, speaking at the United Nations, President Trump himself accused China of meddling in U.S. affairs, and in a high-profile speech on China the following month, Vice President Mike Pence asserted that the United States believes Beijing is seeking to “interfere in the domestic policies of this country” as part a wide-scale influence operation.

Ho’s case may illustrate another, more serious aspect of Beijing’s operations abroad: an attempt to influence the most prominent symbol of the global rules-based order, the United Nations. And the Ho case is not an isolated event. Since 2015, U.S. officials have successfully prosecuted two other related cases of China-linked nonprofits being used to funnel money to U.N officials.

Yet the Ho case also may illustrate a key dilemma for the U.S. government as it attempts to expose foreign agents operating in the United States: While the Trump administration may be eager to prove Beijing is conducting a global influence campaign, it’s often easier to convict someone of financial crimes.

The Department of Justice and Ho’s lawyers declined to comment on any aspect of his case.

Regardless of the prosecution’s arguments in court, Western intelligence officials says Ho’s case fits a broader pattern. Beijing, they argue, is deploying private companies, billionaires, spy agencies, and even charities to achieve its political agenda abroad.

“The Chinese don’t think of it as bribery and corruption,” said one former senior U.S. intelligence official. “They think about it as investment, whether it is at the U.N. or elsewhere.”

* * *

Patrick Ho was born and raised in Hong Kong, a former British colony, but he has long operated inside Beijing’s political orbit. He first emerged on the scene in the 1990s as a delegate to the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference in Beijing, an important arm of the United Front, one of the Communist Party’s political influence agencies. He went on to serve on Beijing’s handpicked task force charged with overseeing Hong Kong’s handover in 1997 to mainland Chinese sovereignty. His service was rewarded when he was appointed as Hong Kong’s minister of home affairs, a position he held from 2002 to 2007.

In 2011, Ho assumed leadership of the Hong Kong-based nonprofit China Energy Fund Committee, founded and funded by the ostensibly private CEFC China Energy, and obtained U.N. accreditation almost immediately, a status granting outside nonprofits access to U.N. grounds, events and personnel. China is a leading member of the committee that grants accreditation and tends to stonewall applications from human rights NGOs or other organizations that might place political pressure on China. The China Energy Fund Committee faced no such difficulty.

The U.N. status gave Ho’s Hong Kong organization, which also has offices in New York City and Arlington, Va., immediate credibility. The committee’s website and print publications were emblazoned with its U.N.-affiliated status, and Ho often touted the U.N. association. China Energy Fund’s website (now down) lists dozens of high-profile individuals as “expert advisors.” Yet when contacted by Yahoo, several of these individuals said that they had never heard of the organization and had never consented to associate with it in any capacity.

The nonprofit hosted events as well, such as colloquia about U.S.-China policy and talks about China’s development model. Ho gave talks promoting the Belt and Road Initiative and held meetings in his capacity as the organization’s director, cultivating relationships within the U.N. But soon Ho allegedly began using his nonprofit to engage in other activities.

In 2014, three years after the China Energy Fund Committee received U.N. special status, Ho began to offer bribes to U.N. officials, U.S. prosecutors allege. Some of those bribes were aimed at securing business advantages and opportunities for the NGO’s parent company, CEFC China Energy, the private Chinese company with ties to the Chinese government and military, according to court documents.

Ho’s first overtures were to John Ashe, an Antiguan diplomat who served as U.N. General Assembly president from 2013 to 2014. Ho introduced himself to Ashe as the head of a U.N.-affiliated nonprofit, honored Ashe at several of the charity’s events, invited Ashe to Hong Kong and then promised Ashe a contribution in exchange for business assistance after Ashe’s term at the U.N. ended. Ho later sent Ashe $50,000, prosecutors allege. The next year, Ho cultivated a similar relationship with Sam Kutesa, Ashe’s successor as U.N. General Assembly president, eventually sending Kutesa a $500,000 payment that prosecutors say was a bribe.

If the allegations are proved true, Ho wouldn’t have been the only Chinese businessman using the cover of an U.N.-affiliated NGO to bribe Ashe. In August 2013, South South News, a U.N.-accredited nonprofit bankrolled by Macau casino tycoon Ng Lap Seng, began depositing $20,000 each month into Ashe’s bank account. Ng was already on the radar of U.S. authorities: In the 1990s, Senate investigators identified him as the likely conduit of hundreds of thousands of dollars in illegal donations to the Democratic National Committee and 1996 Clinton re-election campaign. “Our suspicion was always that Ng had high-level government connections and was protected,” recalled a former U.S. intelligence official familiar with Ng’s activities in the 1990s.

Now almost two decades later, Ng was using South-South News, a small New York-based media outlet that covered development and U.N.-related news, as a front to pay Ashe to get his support for a project to build a U.N. conference center in Macau, according to U.S. prosecutors. In addition to enhancing China’s power and prestige, the establishment of a U.N. conference center in Macau would present China with significant intelligence-gathering and recruitment opportunities, said one former senior U.S. intelligence official.

In 2016, a U.S. attorney involved in prosecuting Ng said that the Chinese government had helped create South-South News and was involved in Ng’s work trying to establish a U.N. conference center in Macau.

The center never materialized, but court filings say that Ng was secretly being investigated as part of a counter-espionage probe of a suspected Chinese spy, and business associate of Ng’s, named Qin Fei; Ng paid to renovate Qin’s $10 million mansion on New York’s Long Island. The mansion was being converted into a conference center for South-South News, Ng’s U.N. nonprofit, said Ng’s lawyer, Hugh Mo, who denies his client had any connection with Chinese intelligence (though Qin, Mo said, was being wiretapped under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act).

U.S. officials believed that Qin was an intelligence officer with the Ministry of State Security, China’s main foreign intelligence agency, said one former U.S. intelligence official, and that he was likely Ng’s handler. The way Beijing operates, said the former official, is that the “billionaire is the icebreaker, and then the Ministry of State Security or United Front goes in behind that person and takes advantages of the opportunities they leave in their wake.”

Ng’s lawyer, however, argues U.S. officials are have a jaundiced view of the relationship between prominent Chinese citizens and the state. “American intel agencies always think everything emanates from top,” he said. “They don’t see all the self-appointed proxies, who take it upon themselves to carry out policy.” Individuals like Ng have “a deeply embedded self-interest,” said Mo, that is also “perceived as patriotic and in line with China’s foreign policy.”

As Ng was funneling money to Ashe, a third effort to influence the U.N. General Assembly president from Antigua was well underway. Sheri Yan, a Chinese-born naturalized American citizen married to a former Australian intelligence analyst, had also cozied up to Ashe. According to emails later uncovered by the FBI, Ashe met secretly with Yan in Hong Kong in April 2012 and agreed to go on Yan’s payroll.

Yan, like Ng Lap Seng, created her own U.N. nonprofit, the Global Sustainability Foundation. And like South-South News, it also received U.N. accreditation and championed the U.N’s millennium goals, an ambitious set of voluntary, country-by-country targets aimed at reducing global poverty. Yan also arranged for bribes to Ashe to benefit three other Chinese businessmen, say U.S. court documents.

The names of the individuals were redacted from court records, but according to a U.S. government document obtained by Yahoo News from Antiguan officials, one of the alleged co-conspirators was a businessman who worked for China National Software and Security Co., a state-owned company with connections to the Chinese military and state security agencies. The businessman allegedly provided a $100,000 bribe to Ashe, facilitated by Yan, according to the document provided to Yahoo. The purpose of the bribe was to encourage the Antiguan government to award China National a contract “to build a national Internet security system” there, according to the indictment.

Attempts to seek comment from China National were unsuccessful.

By 2015, authorities were closing in on the network around Ashe. That year Yan was arrested in the United States, and Australian authorities raided her apartment, suspecting her of working for Beijing. Yan pleaded guilty to bribery charges and was sentenced to 20 months in prison in July 2016. Yan’s husband says his wife, despite pleading guilty to bribery, “has had no connections with any Chinese government agency.”

Ng, the Macau billionaire, was also arrested in 2015 (he was found guilty of bribery in a jury trial and sentenced earlier this year to four years in prison, though he is appealing the sentence and his conviction). Ashe, the center of the bribery scandal, died in a weightlifting accident in June 2016, before he could face trial on tax fraud charges.

That left just Ho, who has been charged under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of funneling $2.9 million to U.N. and African officials, including $2 million in bribes to government officials from Uganda and Chad. Ho has pleaded not guilty on all charges.

* * *

One of the central questions in Ho’s case now is whether his alleged actions were those of a corrupt businessman or, as he contends, simply a well-intentioned NGO representative trying to promote China’s global development plan. The latter may be tough to resolve with some of the allegations. Among other claims, prosecutors say that Ho pursued sanctions-busting transactions with Iran and that he worked with Chinese government security officials to smuggle arms to Libya and Qatar.

Yet Ho is not charged with being a foreign agent.

Those charges can be tough to make without declassifying classified information, something the U.S. government often tries to avoid, said Brian Fleming, a former Justice Department national security prosecutor and a member of the Miller & Chevalier law firm. “If there is a way to try a case without having to declassify classified information, the government is likely going to do that,” he said.

Whether his actions served CEFC China Energy’s interests or Beijing’s may be uncertain, but sometimes those interests overlapped. One alleged payment he allegedly helped facilitate, for example, was intended to help reduce the $1 billion debt that a Chinese state-owned company owed to Chad. The bribe, according to the the criminal complaint, would help CEFC China Energy enter into a partnership with the state company to pursue oil rights in Chad.

CEFC China Energy is not a typical private company, at least by Western standards. The Chinese energy industry is notoriously state-dominated, and the government tightly controls foreign acquisitions. CEFC China Energy, which appeared on the scene around 2010, swiftly gained market dominance and began scooping up foreign deals in Europe, Africa and Asia. The company’s chairman, Ye Jianming, kept a low profile, rarely granting media interviews or speaking in public. But by 2014 the company had become one of the 10 largest private firms in China; in 2017, it bought a $9 billion stake in Russian state oil giant Rosneft.

If, as Ho argues, his alleged payments weren’t about expanding business for CEFC Energy, then what were they for? Ho openly promoted China’s Belt and Road Initiative in his work at the U.N. He hailed it as “Globalization 2.0,” and his nonprofit hosted events and colloquia highlighting the Chinese policy. “We want to promote a better understanding of China, and issues pertaining to China’s position in the world, and try to make friends for China,” Ho said in a previously unpublished interview from 2015 by journalist Isaac Stone Fish, who provided a transcript to Yahoo News.

How successful Ho’s efforts were is hard to say, but the initiative he was promoting, Belt and Road, has made inroads into the United Nations headquarters in New York. Top U.N. officials have begun endorsing the Chinese-led initiative, even as senior officials in the Trump administration, including Pence, have slammed Beijing for pursuing “debt diplomacy.”

According to a spokesperson for the United Nations secretary-general, for its part, the U.N. does not condone bribery and has worked with U.S. law enforcement in the Ho case. “We made it clear when this case began that we would have no tolerance for corruption at the United Nations. We have cooperated with the US authorities in providing relevant information on this case,” Farhan Haq, deputy spokesperson for the U.N. secretary-general, wrote in response to questions from Yahoo News.

Haq also cited the Ng case, where the United Nations disclosed “thousands of documents” and waived “the immunity of officials to allow them to testify at trial.”

At the same time, however, Haq defended U.N. support for China’s Belt and Road, citing its potential to alleviate poverty. U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres “believes that the Belt and Road Initiative has immense potential, promoting access to markets for countries yearning to become more integrated with the global economy,” Haq wrote. “The Initiative, he said, strives to create opportunities, global public goods and win-win cooperation.”

As for Ho, rather than denying the connection between his actions and the Chinese government, he is remarkably now making this link a cornerstone of his own defense by arguing the money he paid was a charitable donation to promote the Belt and Road initiative, not a bribe. According to court filings, Ho’s attorney submitted a letter stating the defense’s intention of calling a witness to testify that CEFC China Energy was “closely tied to the Chinese state during the period relevant to this case and participated in promoting the Chinese state’s agenda.”

Prosecutors say those ties, even if true, are irrelevant. As Ho’s case moves toward trial in New York, the Justice Department has been keeping the focus on financial charges, rather than Ho’s ties to Beijing.

Keeping the case narrowly focused on corruption may make the prosecution’s case easier, but it does have the drawback of precluding a public debate about foreign agents, according to Joshua Rosenstein, a member of Sandler Reiff law firm, which focuses on political law and advocacy.

“There is some significant value in bringing criminal charges involving unregistered foreign agents … in terms of improving or informing the public debate generally, and specifically informing the public debate about foreign actors being involved in public activities,” he said.

That is precisely the point of laws on foreign agents, he added, and prosecuting violations “can lead to sunlight being brought on surreptitious foreign activity even outside of the criminal process.”

Ultimately, whether Ho’s actions were part of Beijing-orchestrated influence campaign — and whether that matters for the charges he faces — or simply a plot to make money for his company may be left up to a jury to decide. His trial is expected to start later this month.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

The CIA’s communications suffered a catastrophic compromise. It started in Iran.

Ending the Qatar blockade might be the price Saudi Arabia pays for Khashoggi’s murder

How Robert Mercer’s hedge fund profits from Trump’s hard-line immigration stance

Trump’s target audience for migrant caravan scare tactics: Women

Photos: Nationwide protests held in support of Mueller probe