The Central Park Five Survived a Horrifying Miscarriage of Justice. Here's What Came Next.

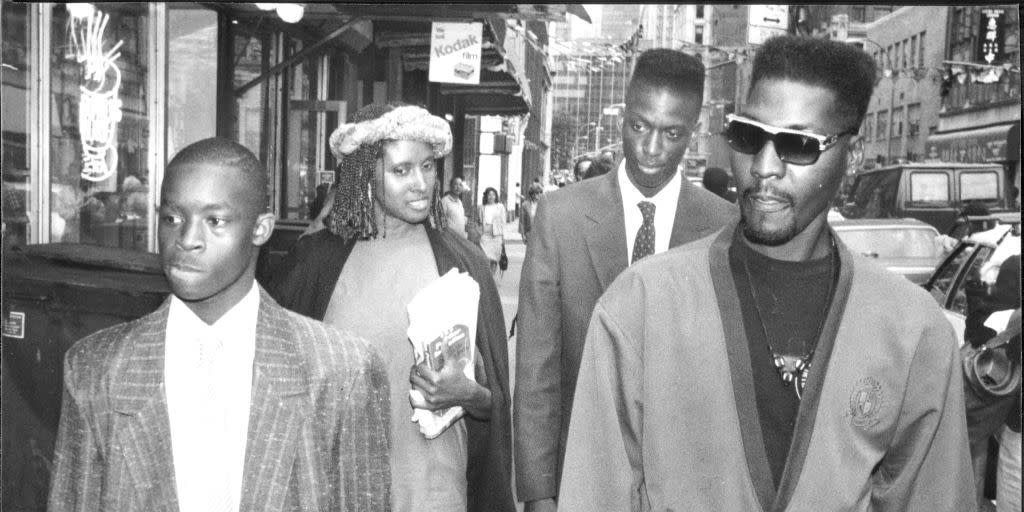

The story of the Central Park Five spans decades, and it’s not over yet. In 1989, Antron McCray, Kevin Richardson, Yusef Salaam, Raymond Santana, and Korey Wise were coerced into confessing to the brutal rape of Trisha Meili, a young investment banker found beaten and near death in New York’s Central Park. Railroaded by detectives and prosecutors who overlooked glaring inconsistencies in their swiftly-retracted confessions, the boys were convicted and served between six and 13 years in jail. But after the real perpetrator confessed, their convictions were vacated in 2002. Twelve years later, the city settled a civil rights lawsuit brought by the men for $41 million.

But the story continues today. In the wake of Netflix’s When They See Us, a four-part miniseries based on the case, former Five prosecutor-turned-novelist Linda Fairstein was dropped by her publisher and resigned from the board at Vassar. And in the years since their exoneration, the men Fairstein once prosecuted have become outspoken advocates for criminal justice reform. Here’s what they’ve been up to in recent years.

Antron McCray

In 1989, Antron McCray was a shy fifteen year old living with his parents, Linda and Bobby McCray, when he was coerced into falsely confessing to being involved in Meili’s rape. According to Central Park Five author Sarah Burns, McCray spent the first five years of his sentence at the Brookwood Secure Center, a juvenile detention facility more than one hundred miles away from his family in Harlem. He was later transferred to a maximum security adult prison for the final two years of his sentence. During his incarceration he earned a GED and began work on an associate’s degree, but the boys’ educations were abruptly cut short after New York’s then-governor George Pataki ended higher education programs in the state’s prisons.

He was released from prison in September 1996 and moved to Maryland three years later, where he found work as a warehouse forklift officer. These days, McCray is a married, 45-year-old father of six living in Atlanta, Georgia, but he still bears the scars of his ordeal. "I’m damaged, you know?” he told The New York Times last month. I know I need help. But I feel like I’m too old to get help now … But it eats me up every day. Eats me alive. My wife is trying to get me help but I keep refusing. That’s just where I’m at right now. I don’t know what to do."

Kevin Richardson

The youngest of the five, Kevin Richardson was a baby-faced fourteen-year-old when he was first arrested, and went on to serve five years at a maximum-security youth prison before being transferred to the adult, maximum-security Coxsackie Correctional Facility. While imprisoned, he earned an associate’s degree and began work on a bachelor’s.

He was released in June 1997. Though he had a supportive family that included four doting older sisters, like many of the other young men, Richardson struggled to adapt to freedom. Burns wrote wrote that Richardson had grown unaccustomed to handling money and was “horrified” by the stories he heard at his court-mandated sexual predator group therapy.

Today Richardson, his wife, and two children live in New Jersey. As of Burns' 2012 writing, he and his siblings still returned to the Harlem apartment they’d grown up in every Friday to visit their mother. But Like McCray, Richardson has struggled with his years of false imprisonment. “PTSD is real and I go through that,” he told The New York Times. "People might think on the outside looking in that I’m doing swell because we got the settlement. That doesn’t erase the time that I did. We always say we have invisible scars nobody sees. And no matter how you cover it, the scab will keep coming off."

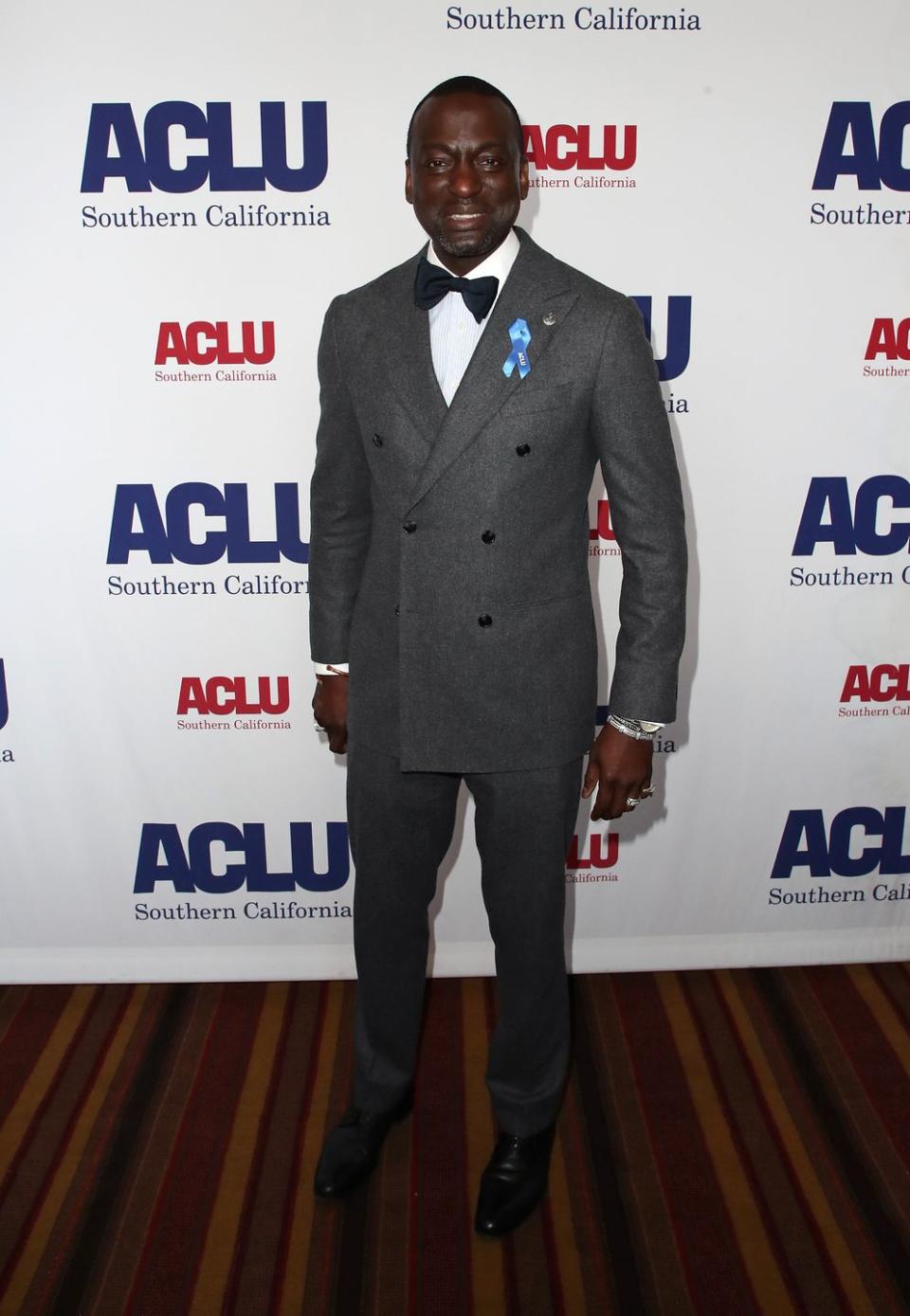

Yusef Salaam

Salaam served his sentence at the Harlem Village youth facility until he was 21, then transferred to the adult maximum-security prison Clinton Correctional. While in prison, Salaam focused on his Muslim faith and completed a bachelor’s degree. He was released in March of 1997, and married shortly after regaining his freedom. Though he and his then-wife went on to have three children, the marriage didn’t last. “Yusef believes that he might not have ended up divorced so soon if he hadn’t rushed into it,” wrote Burns, "trying to make the most of his time on the outside.”

Salaam has since remarried, and is now a father of ten residing in Georgia. He’s a public speaker, criminal justice reform advocate, and poet who’s told his story to audiences around the world. In 2016, then-president Barack Obama honored Salaam with a Lifetime Achievement Award.

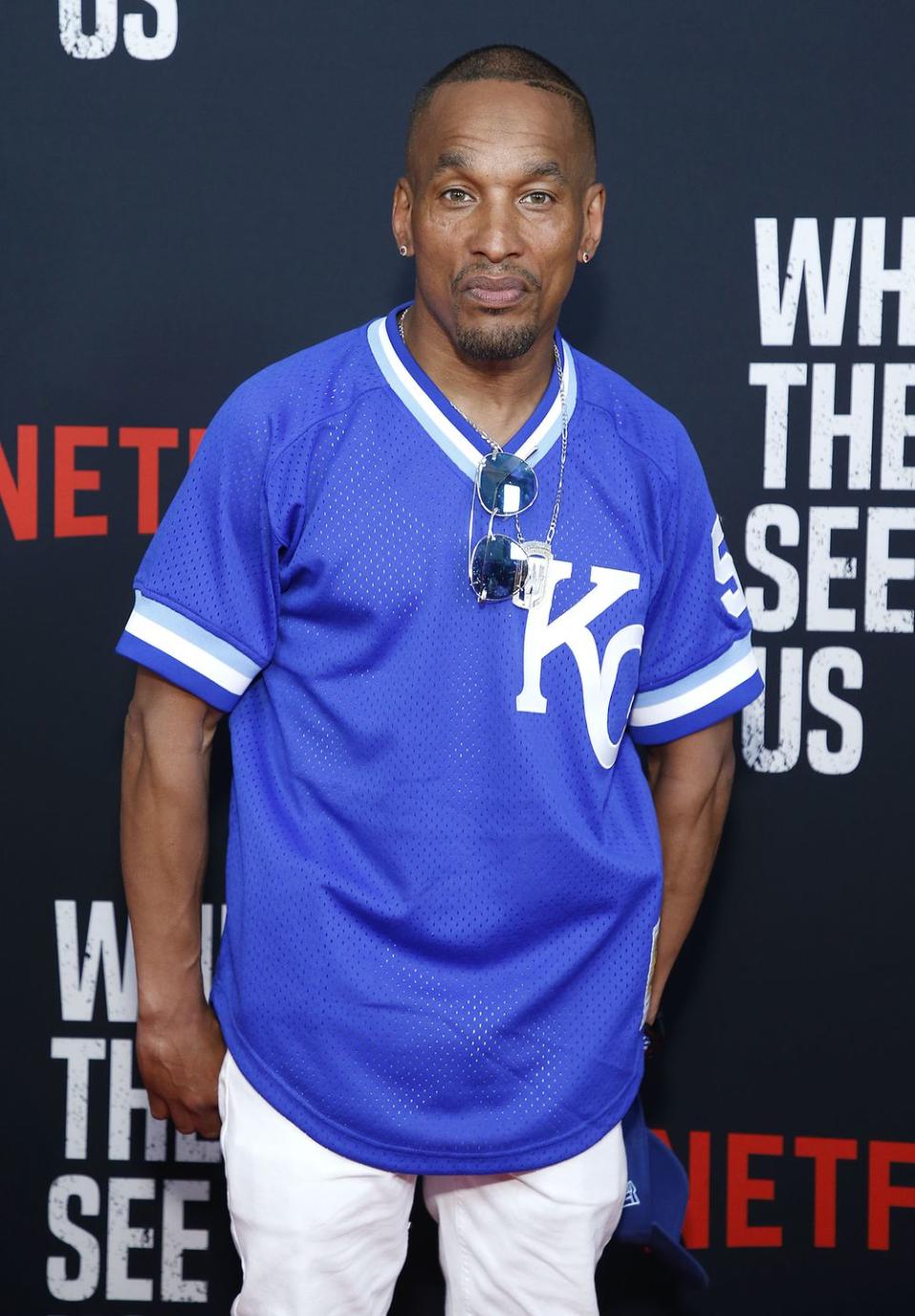

Raymond Santana, Jr.

Santana was released from prison in December 1995. He was just 14 at the time of his arrest, and like Salaam, Richardson, and McCray, served his sentence at a juvenile prison until he turned 21, before transferring to an adult prison. He was permitted to return home for a visit in 1993 to say goodbye to to his mother, who was dying of cancer.

As depicted in When They See Us, Santana’s initial freedom was short lived. Branded a violent sex offender, he struggled to find work, and ended up serving subsequent prison stints. After 18 months of freedom, he was convicted of violating his parole curfew and served a further 20 months in jail. He then was free for six months before being caught in possession of crack cocaine. He plead guilty to intent to sell the drug and received a sentence of three-and-a-half to seven years, though his incarceration was cut short after he and the other men were exonerated for Meili’s rape in 2002.

Santana now lives in Georgia, and has founded a clothing company. In 2015, he tweeted at filmmaker Ava DuVernay, suggesting that she make a film about the Central Park Five. She ended up following his advice, and directed and co-wrote When They See Us. DuVernay has confirmed that the message inspired her to create When They See Us. "Ava was always my choice to do this series. I never met the woman, I didn’t even know who she was, but I’d watched Selma,” he told The New York Times. “There’s a part where [Martin Luther King, Jr.] is confronted by [his wife] Coretta with recordings [of him with another woman], and I felt like that was bold to put in the film. By showing that, it showed the human side of this man who was put on a pedestal. And it told me that she had no fear of telling the truth.”

Korey Wise

Wise’s suffering as a result of his false conviction was so profound that DuVernay dedicated the majority of the series’ final episode to his experiences. At 16 he was the eldest of the five boys, and under the law at the time spent his entire incarceration at violent adult jails and prisons. He also served nearly twice as long as the other boys did-almost 14 years in total.

While he completed a GED during his incarceration, he didn’t receive the resources needed to address his hearing problems or learning disability while in prison. Once freed, he found work in construction and was also employed for a time by Al Sharpton as an office cleaner.

When the city finally settled with the men, Wise, who’d served the longest sentence, earned more than $12 million dollars. He still lives in New York and works as a criminal justice reform activist. In 2015, he gave a donation of $190,000 to Colorado’s Innocence Project. It was renamed the Korey Wise Innocence Project in his honor.

('You Might Also Like',)