Central America’s Wars of the ’80s Still Haunt the U.S.

Forty years ago this week, on July 19, 1979, rebels who called themselves Sandinistas overthrew the Nicaraguan dynasty of the Somoza family that was first installed by U.S. Marines in the 1930s. By 1983, Reagan was using the largely Marxist leadership of the Sandinista regime to feed paranoia about Communist encroachment, as if Central America represented an existential threat to the United States. His policies included overt support for business and military elites, tacit support for death squads, and covert backing for anti-Sandinista Contra rebels accused of gross human rights abuses. If Congress would not back him, Reagan warned, there would be “a tidal wave of refugees—and this time they’ll be ‘feet people’ and not ‘boat people’ [like those who fled South Vietnam after the Communist takeover in 1975]—swarming into our country.”

Today, Central American refugees are indeed coming to the U.S. border in numbers the Trump administration claims are overwhelming. The reasons they flee their homes can be traced to this basic fact: neither the revolutions nor Reagan’s counter-revolutions delivered on their promises, while vast numbers of Central Americans continue to live in poverty and fear.

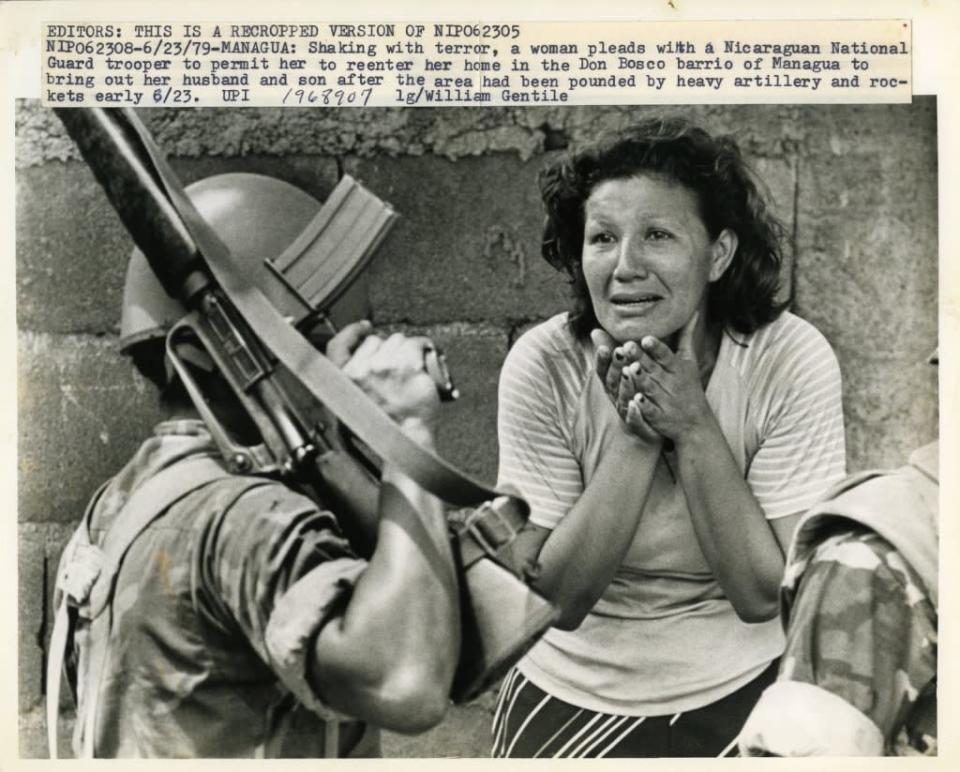

Bill Gentile was a young freelance reporter and photographer in Central America in the 1980s. This series, beginning today, takes us into the crucible of the region’s uprisings, which still haunt the conscience of the United States.

—Christopher Dickey, World News Editor

Part I: The Revolution (1978-1979)

Like many journalists who covered Nicaragua, I have been deeply affected by my long relationship with that country and her people. I lived and worked there during some of the most formative years of my life, and the life of Nicaragua herself. It's where I first witnessed war. It's where I first saw violence used to achieve political and social change. It's where I met my first wife. It's where I forged life-time friendships. It's where I came to recognize privilege and power as enemies. Nicaragua also is where I came to understand and to cherish my role as journalist.

—Bill Gentile

Contra rebels patrolling the northern mountains of Nicaragua. One soldier wears a ‘USA’ baseball hat, representing the country that aids their anti-Sandinista struggle.

Night Moves

In a small complex of cabañas tucked away under coconut trees on the outskirts of the Nicaraguan capital, Managua, where a contingent of international journalists had set up a base of operations, I was up late one night listening to stories of war. Guy Gugliotta was a Miami-based correspondent for the Miami Herald. Tall and lanky with a soft voice and tired eyes, he didn't easily fit my preconceived notion of a Vietnam veteran and former Swift Boat commander. But he was.

I’ve never been to Vietnam but I grew up on imagery of that war in the pages of Life magazine. Huge color photographs made by some of the most courageous and most talented photojournalists of the era arrived each week at my home in the steel town of Aliquippa, Pennsylvania, about 40 minutes northwest of Pittsburgh. They planted within me a lifelong fascination with imagery and journalism.

In Managua that night, I smoked Marlboro reds while Gugliotta and I worked on a bottle of Nicaraguan rum and he talked about how he kept himself and his men alive in Vietnam while executing one of the most dangerous assignments of that decade-long war; how he anticipated and calculated for every contingent; how his eyes scoured every curve in the rivers that he and his men were assigned to patrol; how a flash of light off a metal surface or a reflection from the river bank could be the precursor of an ambush and the death of him and the men under his command; how he would instruct his men to respond; and, ultimately, how he would help get himself and his men back home.

In the background, I remember, Bob Seger sang "Night Moves” on a cassette plugged into the recorder I used to file reports for ABC Radio News.

I didn’t know then that Gugliotta’s lessons on guerrilla warfare might help save my life in the not-so-distant future.

The Somozas and Sandino

It was 1979 and I was a freelance journalist on a trip through Central America to see first-hand the stories that I had been editing on the desk of United Press International (UPI) at my base in Mexico City. The bureau there covered not only Mexico, but Central America and the Caribbean as well. I also freelanced for ABC Radio, the Baltimore Sun, and the Kansas City Star. At the time, I was more a print guy than a photo guy.

I landed in Managua only days before the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional (FSLN), or Sandinista National Liberation Front, declared its "final offensive" against the U.S.-backed rule of President Anastasio Somoza, who had inherited the regime from his father in 1957.

A popular insurgency against Somoza family rule had been festering for years and the FSLN managed to seize the leadership role and channel the rebellion into a final push against the regime.

The United States’ role in Nicaragua is not one that most Americans can be proud of. U.S. Marines invaded and occupied the country on numerous occasions and for various periods of time beginning in 1909. The first Somoza—Anastasio Somoza García, known as “Tacho”—was installed as the head of the Nicaraguan National Guard, set up by the U.S. as a supposedly non-partisan constabulary. That did not last long.

Augusto César Sandino, who had led a guerrilla war against the U.S. Marines, finally agreed to make peace in 1934, only to be murdered by Somoza’s guard with U.S. complicity. And Tacho seized all power in 1937.

In return for its role as staunch U.S. ally and anti-communist bulwark in Central America, the United States supported the Somoza dynasty for four decades. (In 1939, Franklin Roosevelt is supposed to have said of Tacho, “He’s a son of a bitch, but he’s our son of a bitch.”) This despite the regime’s consistent record of grotesque human rights violations.

Then, for six weeks in the summer of 1979 Nicaragua suffered a national convulsion that left some 30,000 of her citizens—in a country of only about 2.5 million inhabitants at the time—dead.

A Bullet in the Head

As it became clear that the successor to the dynasty, Anastasio “Tachito” Somoza Debayle, was in trouble, journalists from around the world converged on Managua. These included a team led by ABC television correspondent Bill Stewart, and since I was a stringer for ABC Radio, I briefly worked with the ABC team as a translator.

By 1979 I was pretty fluent in Spanish, an asset essential to negotiate one’s freedom or one’s life with mostly young, scared, exhausted and sometimes very pissed-off soldiers. Stewart had arrived on the scene after covering the revolution in Iran. He spoke no Spanish.

On June 20, 1979, a squad of Somoza's national guardsmen manning a Managua checkpoint stopped the van carrying Stewart and his colleagues. (As it happened, I had left the ABC team a couple of days earlier.)

Stewart and his Nicaraguan translator approached the soldiers as the camera and sound men in the van secretly filmed the event through the windshield. The guardsmen made Stewart kneel, and then lie face down on the city street. One of them pumped a single bullet into the back of his head. They also killed Stewart’s Nicaraguan translator, out of sight of the cameraman inside the van.

The global broadcast of that footage crushed support of the Somoza regime. Even its most stalwart anti-communist U.S. congressional defenders could not continue to support the family’s continued rule.

Suicide Stringers

In response to the killing, the vast majority of journalists covering the revolution evacuated the country, some in protest and others out of concern for their own safety. I was one of a handful who stayed.

John Hoagland was another.

He was freelancing for the Associated Press (AP), making $25 for every picture the international wire service transmitted from Nicaragua to its headquarters in New York City. John was a surfer from California, and he looked it:, tall and tanned with sun-tinged hair. Rumor was that he once was a bodyguard for Angela Davis and carried a .357 Magnum while on the job. A bold Fu Manchu moustache added to his reputation as a take-no-bullshit dude but perhaps masked the decency and the kindness that was his core.

Young, hungry and determined to “make it,” John and I began to work together despite the fact that we worked for competing wire services. We took risks that perhaps more sensible journalists might not have considered. The Somoza regime’s use of small aircraft to bomb and strafe the eastern barrios of Managua had become routine during the final offensive. Sandinista cadres had taken positions there and the regime conducted air raids every afternoon, so most journalists stayed away from the place until the raids were over. But not John and I.

We made our way one afternoon past rebel barricades and checkpoints along the Carretera Norte that connects the capital to the international airport. We wanted to get close to insurgents confronting a National Guard position along the same key route. As one of the regime’s planes fired rockets at the insurgents, John ducked for cover and I ran toward the open door of a nearby house in a bid to do the same. That’s when a rocket from one of the planes plowed through the roof of my intended refuge, blowing debris through the front door. Three steps faster and I would have eaten a shrapnel sandwich.

After that incident, our colleagues began calling John Hoagland and me the “suicide stringers.”

Covering the final offensive was a non-stop scramble for information. Fighting between the National Guard and the Sandinista-led insurgency moved from one city to another on an almost daily basis. Death tolls. Body counts. Casualty reports. Refugees. Press conferences. Sandinistas seizing control of towns and cities across the country. More casualty reports. To stay abreast of these always-moving events, the UPI team relied heavily on our “secret weapon.”

In his early 60s and blessed with an authoritative demeanor, Leonardo Lacayo was a long-time journalist and local stringer for UPI. At his home on the outskirts of the city, “Don Lacayo” had a short-wave radio system he used to monitor communication between Somoza and his national guardsmen in the field. So we often knew what was happening before it actually happened. Lacayo was such a closely guarded secret in the super competitive world of breaking news coverage that the UPI journalists were forbidden to use his real name even in private conversation, out of concern that our competitors would find him out. We were allowed only to refer to him as “El Hombre”—The Man.

The Bunker

Anastasio Somoza’s bunker, or command post, was a stone’s throw from the Intercontinental Hotel in what remained of Managua. The city was severely damaged in a 1972 earthquake that killed tens of thousands of its citizens. On the morning after the dictator and his family fled the country, Nicaragua’s National Guard disintegrated as its members stripped off their uniforms and fled. Many tried to pass themselves off as civilians and headed north to the border with Honduras.

A few yards from the bunker, two national guardsmen were trying to jump-start a car to join their fleeing colleagues. They asked me and a colleague to help them push their car so they could be on their way. As my colleague and I took our places behind the trunk of the car, we could see the body of a third guardsman lying on the back seat. The two guardsmen were taking their dead with them as they fled the incoming Sandinista fighters.

The following day and not far down a main street from Somoza’s bunker, the plaza in front of Managua’s metropolitan cathedral filled with thousands of Nicaraguans welcoming the incoming Junta of National Reconstruction, victorious Sandinista fighters and followers.

Tomorrow: Terrible and Glorious Days—The Contra War (1982-1989)

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.