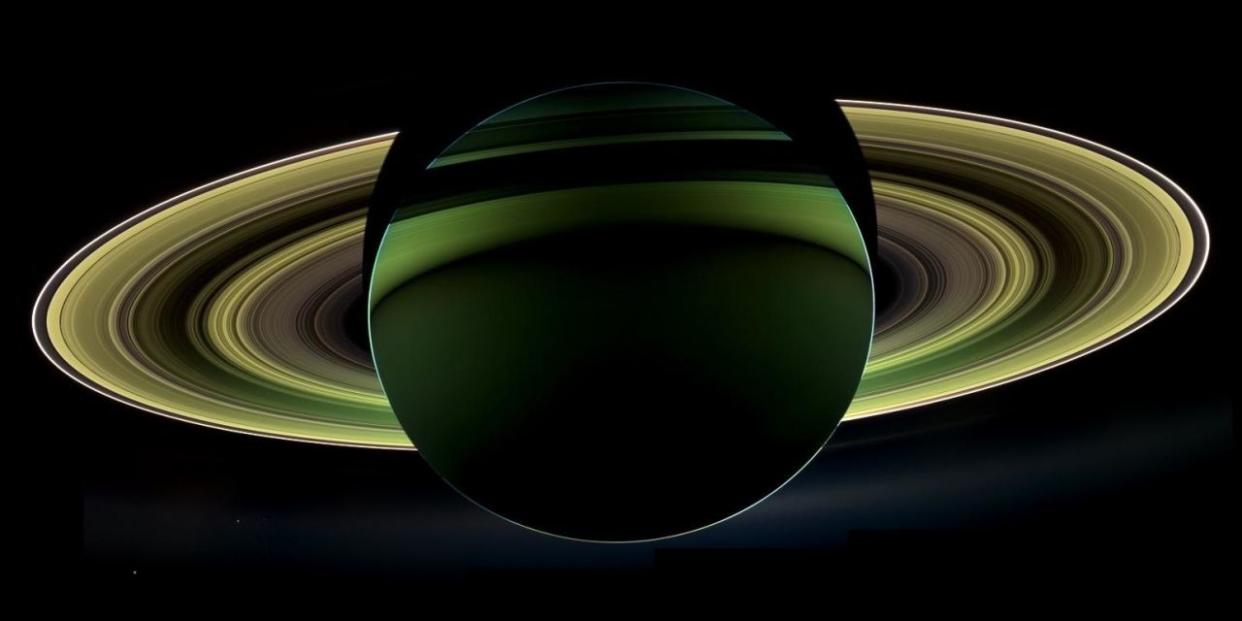

Cassini Spacecraft Begins Ring-Grazing Orbits Before Plummeting to Its Doom

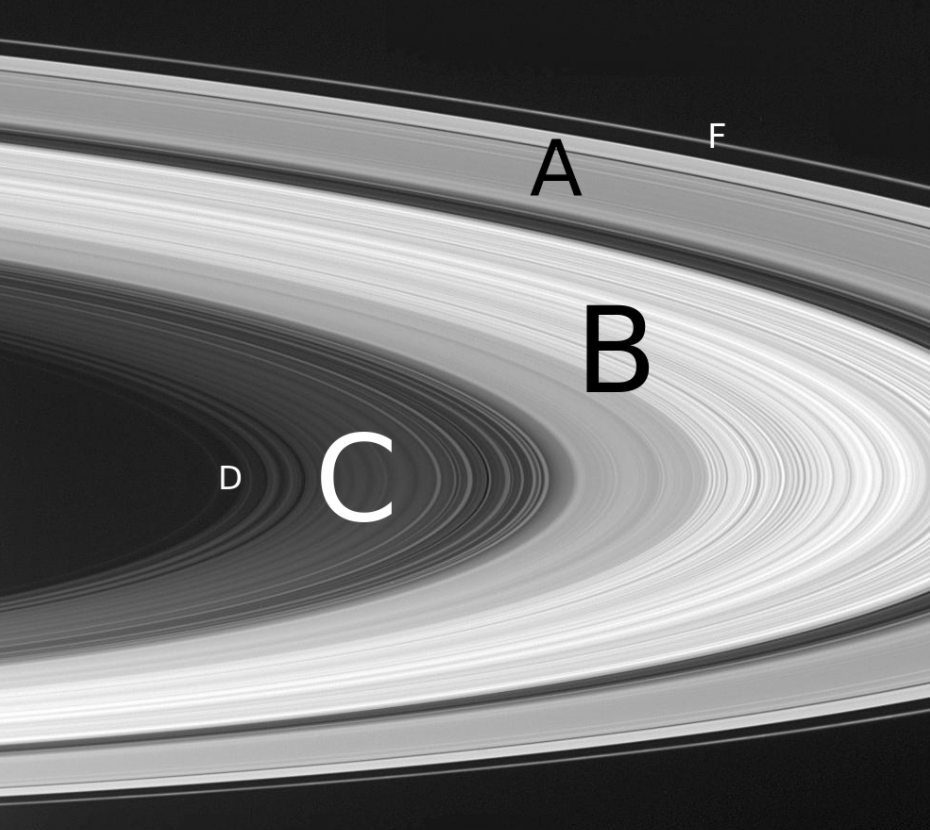

The Cassini spacecraft has orbited Saturn for the past 12 years, but now it's off and running on its final two missions. On December 4, the craft skirted the edge of Saturn's F ring-the outermost of the easily visible rings-in the first of 20 orbits. Once those 20 are completed, the spacecraft will fly in between Saturn and its rings. It's an unprecedented and risky maneuver that will bring us the closest look at Saturn we have ever seen.

[contentlinks align="left" textonly="false" numbered="false" headline="Cassini%20Mission" customtitles="Hundreds%20of%20Orbits%20From%20NASA's%20Cassini%20In%20One%20GIF" customimages="" content="article.24048"]

During the 20 ring-grazing orbits that will take place over the next four months, Cassini will get a very good look at Saturn's outer F ring, a 310-mile-wide disk of spiraling ice and dust bound by the small moons Prometheus and Pandora. One of Saturn's most active rings, the F ring is a never-ending flux of spirals and knots where the particles bunch up and collide with one another. Sometimes Prometheus even passes through the ring, leaving streamers and tendrils of icy dust in its wake.

From the vantage point at the perimeter of the F ring, Cassini will also have a fantastic view of Saturn's giant A ring. Within the A ring, moonlets are constantly forming and being shredded to bits, revealing their presence to Cassini's cameras as propeller-shaped wakes in the icy material that makes up the ring. Researchers hope to use these moonlets of Saturn as a microcosm to study planet formation, as many of the same processes may be taking place in Saturn's rings that occur in the protoplanetary disks of ice and dust that surround newly-formed stars.

After the 20 ring-grazing orbits, Cassini is going to get even closer for five additional months of science, adjusting its orbit to dive in between Saturn and its rings for the very first time in what has been dubbed the Grande Finale. These 22 planned orbits don't come without risk, as the spacecraft could be hit and destroyed by material that strayed outside of Saturn's rings. The science team plans to use Cassini's antenna as a shield as it forges ahead into the unexplored space, but "there is always a chance that a ring particle might hit Cassini in a key area, and it will stop functioning," Linda Spilker, the Cassini Project Scientist at JPL, told National Geographic.

From this incredibly close vantage point, approaching only 1,000 miles from the cloud tops of Saturn, Cassini will be able to search for answers to some of the great unanswered questions about the ringed planet. Are the rings as old as the planet itself, or did Saturn rip apart an asteroid that came to close and keep the bits as a trophy? How does the hexagonal storm at Saturn's north pole retain its non-circular shape? What does the high-pressure gas interior of Saturn actually look like?

After the 22 orbits between Saturn and its rings are completed, the finale of the Grand Finale will be underway. Cassini, low on fuel, will be intentionally crashed into Saturn to prevent the spacecraft from incidentally impacting one of Saturn's pristine moons down the line. The spacecraft will continue to beam data back to Earth until it is vaporized in the thick atmosphere of Saturn to become a small part of the very planet itself.

Source: NASA via National Geographic

You Might Also Like