Cassini’s Grand Finale: NASA Spacecraft’s ‘Final Kiss’

In just two weeks, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, having used up almost all of its fuel by circling Saturn for 13 years, will wave goodbye to Earth and plunge into its old companion, melting within minutes.

The scientists who have led the mission are sad to see it go, but they always knew this was coming. “We planned this end,” said Linda Spilker, a project scientist, during a press call held by NASA on Tuesday. “We had the fuel last exactly the amount of time we needed to get to Saturn’s summer solstice, so it’s time.” Even better, the bitter end will make sure that nothing contaminated by Earth’s microbes can reach potentially habitable moons like Enceladus.

But before Cassini meets its fate, it has a whole lot of science to get done. And because NASA didn’t want to risk the spacecraft earlier in its mission, what’s left are some of the coolest and most dangerous maneuvers. Now, even if everything goes wrong, NASA doesn’t have much to lose, Cassini project manager Earl Maize said, since “the spacecraft has been used to its fullest.”

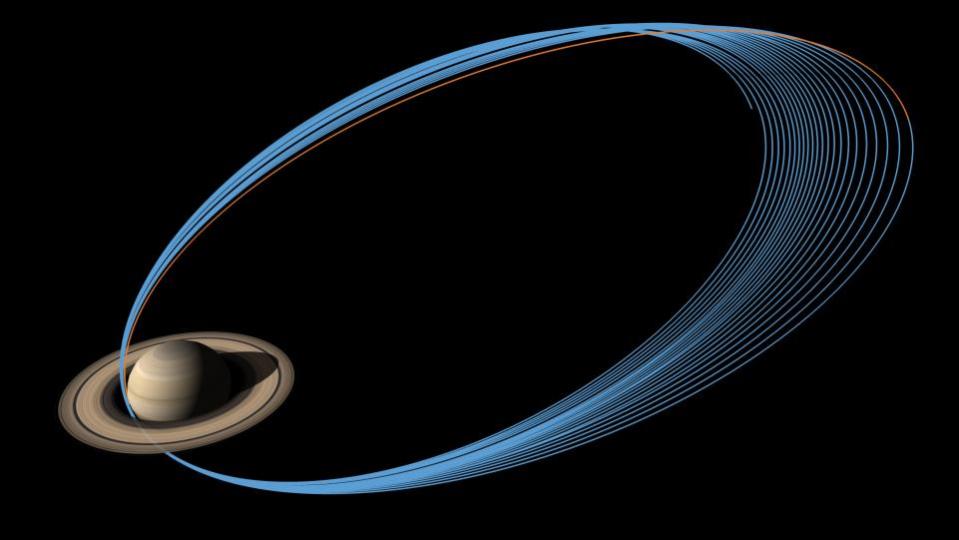

Right now, Cassini is 20 loops into its closest ever tango with Saturn, during which it slips through the gap between the planet and its rings, then dances away to approach again from the same angle. Each orbit takes less than a week in Earth time, and its last skim beneath the rings is scheduled for September 9.

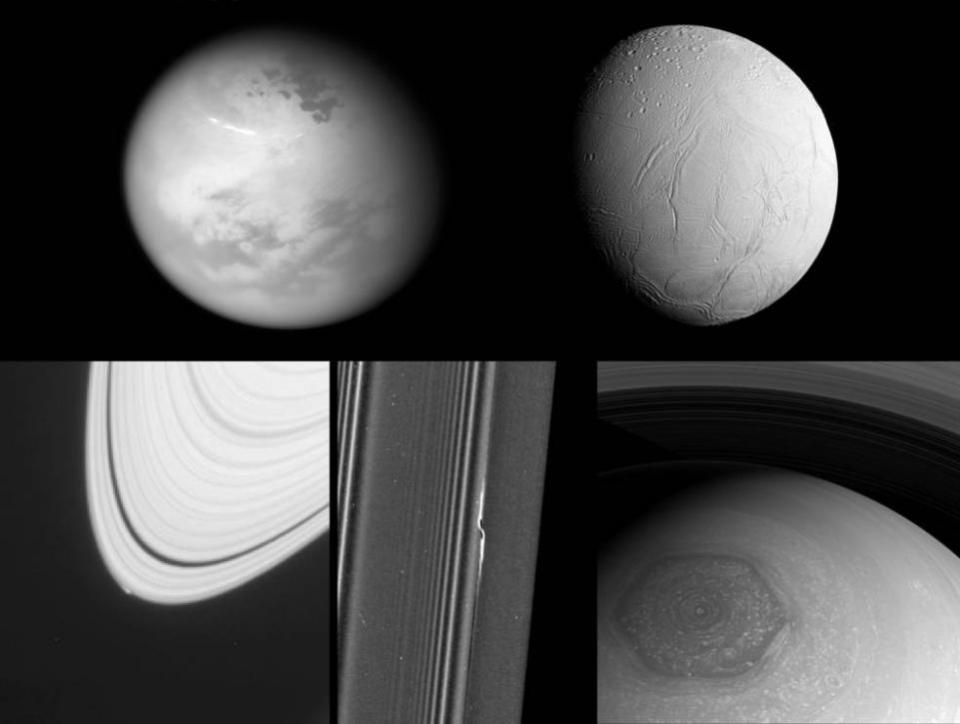

The dives, 22 in all, offer not just a new perspective on the rings, but also the chance to learn how they were formed. The key piece of information scientists are missing here is how much material is actually in the rings. If they’re larger, that means they’re older—possibly just as old as Jupiter itself. If they’re smaller, which is currently looking more likely, it means they’re younger, and possibly created by a comet or a moon creeping too close to Saturn and being shredded by its massive gravity.

Cassini’s last dives also are also giving scientists front-row seats to chemical interactions happening between the rings and the outermost layer of the planet’s atmosphere, which have turned out to be much more complex than scientists had expected. And the spacecraft has already dipped cautiously into the heavy atmosphere to gather data about what it’s made of.

“All of this is actually good news,” says Spilker. “Scientists love mysteries, and the grand finale is providing mysteries for everyone.” She added that although the dramatic circumstances and exotic location are new, the team’s day-to-day process—gather as much data as possible—is basically the same as it's always been.

And, of course, photographs are a huge priority for these last dives. The team has been particularly intrigued by the increasingly close views of the rings, which are showing patches of clumpiness and streakiness that scientists can’t yet explain.

As Cassini leaves the rings for the final time, it will swing back out into space, sliding near Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, in what project manager Maize calls the “final kiss.” The pull of Titan’s gravity, even from more than 74,000 miles away, will steal a bit of the spacecraft’s momentum—and that will mean that the next time it flies by Saturn, it won’t be able to escape.

On that last ride in toward the massive planet, Cassini will snap one last burst of photographs on September 13 and 14. These last postcards home will include a last view of Titan’s weather, a glimpse of the moon Enceladus setting behind Saturn, a color montage of the aurora that circles Saturn’s north pole, and a checkup on Saturn’s tiny, wanna-be moon, nicknamed Peggy, which may be breaking free of the planet’s rings.

At about 4:22 p.m. Eastern time on September 14, the spacecraft will turn toward Earth one last time, sending home all the images and data collected so far. Cassini is so far away that the signal will take an hour and a half to reach us.

With all its knowledge safely submitted, the spacecraft will transform itself from an orbiter into an atmospheric probe. Late in the night, it will stop storing data, setting up a stream straight to Earth, with only seconds of delay to suck as much science as possible out of its last dozen hours.

Then, with eight of its instruments turned on, Cassini will plummet into Saturn’s thick atmosphere. “There is absolutely no coming out of it on this one,” Maize said. “We are going so deep into the atmosphere, the spacecraft doesn’t have a chance.”

As it goes, it will gather data for as long as it can, including measuring the ratio of hydrogen to helium and identifying chemicals found in very small quantities, the sort of measurements scientists can’t take from Earth.

In its last moments just before 8 a.m. Eastern time on September 15, Cassini will be traveling at 76,000 miles per hour into the gas giant. “We’ll basically disintegrate,” said Julie Webster, who oversees the spacecraft’s health. “We’ll melt long before we hit any surface of Saturn.”

The first to go will be the thin, gold-colored thermal blankets that have kept Cassini warm on its journey, then the aluminum that shields its recorders. Next, the small plutonium heart that has helped power the spacecraft will melt, safe inside the box designed to isolate it in case anything went wrong during the spacecraft’s launch 20 years ago. That box, made of sturdy iridium, will be the very last piece of Cassini.

Then it, too, will melt away, dissipating into the vastness of Saturn, leaving the questions and answers of scientists here on Earth as Cassini’s only legacy.

Related Articles