Caprock Chronicles: A racially charged trial in Lubbock part one: The bootlegger and the sheriff

Editor’s Note: Jack Becker is the editor of Caprock Chronicles and is a Librarian Emeritus from Texas Tech University. He can be reached at jack.becker@ttu.edu. Today’s article about the 1947 Lubbock trial of George Holland is the first of a three-part series by frequent contributor Chuck Lanehart, Lubbock attorney and award-winning history writer.

The accused man had a name, but in newspaper headlines throughout Texas and beyond, he was referred to as "The Negro."

In the mid-20th Century, it was common for newspapers to refer to persons of color accused of crimes as “Negro” and “Mexican.” Occasionally, other racial slurs were seen in print. No racial slurs were used in news coverage of the George Holland trial, but anyone who read about the case knew he was a Black man accused of killing a white sheriff.

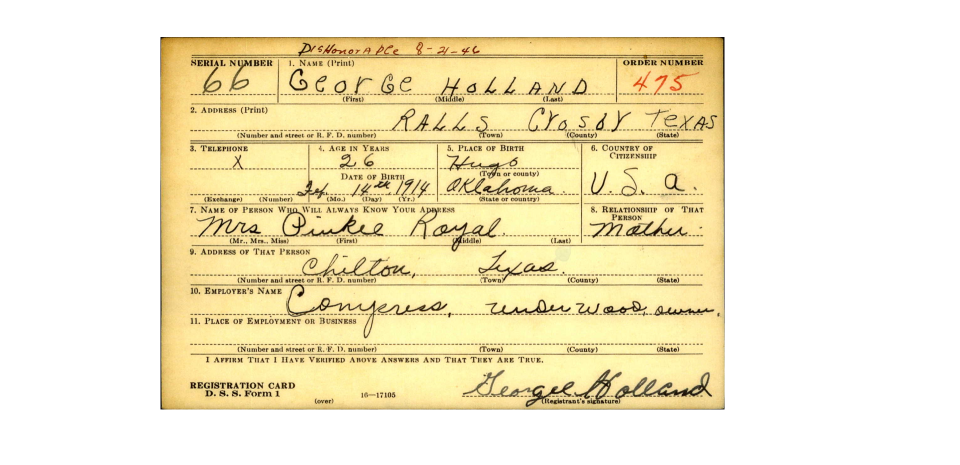

Born on Valentine’s Day, 1914, in Oklahoma, George was one of six children reared by his mother in Ralls, Crosby County, Texas. He completed the fourth grade and learned to read and write. As an adult, he was rather small—five feet nine inches tall and 145 pounds — with a dark complexion, black hair and brown eyes. He did not drink or use tobacco and attended the Baptist church.

At age 19, Holland was married to Hattie Garrett in Ralls. Three years later, he spent two years in prison for a perjury conviction. In 1944, he joined the US Army. He was injured in action in WWII, and he was dishonorably discharged for unknown reasons in 1946.

Holland returned to Ralls, a “dry” town. The State of Texas outlawed most alcohol sales, and there were lots of thirsty folks in Crosby County. Holland, unable to find work in his previous jobs—laundryman and lineman—became a bootlegger, a dangerous business. Twenty years earlier, Crosby County bootleggers were involved in a feud which resulted in violent deaths.

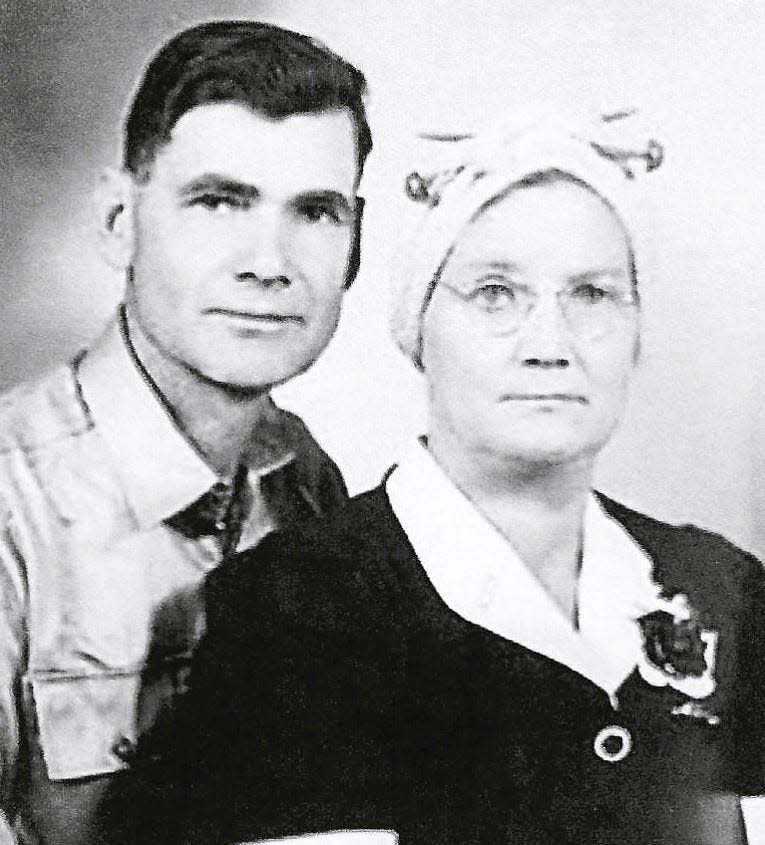

Julius Jewell Pierce was born in 1900 in Hill County, Texas. His father Quill was a farmer and former Sheriff of Hill County. “Jewell” dropped out of high school and in 1920, he married a local girl, Carl Brantley. The couple began farming and raising kids. The growing family moved to rural Crosby County in 1929, rented a farm and joined the Mt. Blanco Missionary Baptist Church. By 1934, they owned their own small farm and a new Ford sedan.

Pierce presented a dashing figure, six feet three inches tall and slim, with brown hair, brown eyes, a square jaw and a tough countenance. He could have passed for a movie Texas lawman. With encouragement from friends and the support of his family, he followed his father’s example and ran for Crosby County Sheriff. He was elected and took office January 1, 1947. His wife and eight children were proud, but they worried about his dangerous new job.

Pierce — known as “J.J.” in news accounts — immediately began enforcing liquor law violations. One of the sheriff’s targets was George Holland, who Pierce arrested several times on liquor law and vagrancy charges in the first few months of his term.

Trouble was brewing.

On the night of Saturday, Aug. 2, 1947, Sheriff Pierce told his family he was going to Ralls to “make a raid.” He went alone to Holland’s neighborhood in “The Flats.” He found a cache of liquor in an outhouse and lay in wait until shortly before midnight, when he observed Holland leave a house and remove bottles from the shack.

According to news accounts, the lawman “challenged the negro, who submitted to arrest, but as the two were walking from the scene, 35 to 50 feet from the (man's) house, the black, walking on the sheriff's right, jerked the officer's gun from its holster and started shooting.”

The first of five shots tore through the Sheriff’s right arm, into his side and into his heart. Pierce fell, grabbing for his gun as bullets swiftly ripped through his hand, head and cheek. He was left to die lying on his side in a weedy vacant lot, with large powder marks on his head, indicating shots were fired at point blank range.

Witnesses provided a license plate number for the late-model car Holland was seen driving as he fled the scene. An army of law enforcement officers traversed West Texas in search of the vehicle.

The license plate described was spotted on a car Sunday morning in a segregated neighborhood of Amarillo. News accounts reported Holland appeared at the home of an “Amarillo negro woman” and told her he was in trouble. At 7 a.m., police found him asleep on her divan, and he was arrested.

The prisoner should have been taken to the Crosby County Jail, in the jurisdiction where the crime occurred. However, threats of a lynch mob had been reported, so Holland was housed in the more secure Lubbock County Jail to await his fate.

Wire services spread the news, and on Aug. 4, dozens of bold headlines used the word “negro” to tell the story. In Lubbock, “Negro Held in Ralls Shooting.” In Amarillo, “Hold Negro in Murder of Sheriff.” In San Angelo, “Negro to be Charged in Shooting.”

Part Two of this series will be published in next Sunday’s Lubbock A-J.

This article originally appeared on Lubbock Avalanche-Journal: Caprock Chronicles: A racially charged trial in Lubbock part one: The bootlegger and the sheriff