Caprock Chronicles: The historic treasures of Blanco Canyon, part one

Editor’s Note: Jack Becker is the editor of Caprock Chronicles and is a Librarian Emeritus from Texas Tech University. He can be reached at jack.becker@ttu.edu. Today’s article about treasure in Blanco Canyon is the first of a two-part series by frequent contributor Chuck Lanehart, Lubbock attorney and award-winning Western history writer.

It was the spring of 1541, and an army was camped in a canyon somewhere on the “Llano Estacado,” in what is now the Panhandle/South Plains region of Texas. Those encamped survived a terrifying storm.

A soldier wrote of the experience. “A tempest came up one afternoon with high wind and hail, and in a short time, hailstones as big as bowls, or bigger, fell as thick as raindrops. The (Black men) protected the horses by holding large sea nets over them, with helmets and shields. The hail broke many tents, battered many helmets, wounded many horses, and broke all the crockery of the army, which was no small loss because they do not have any crockery in this region.”

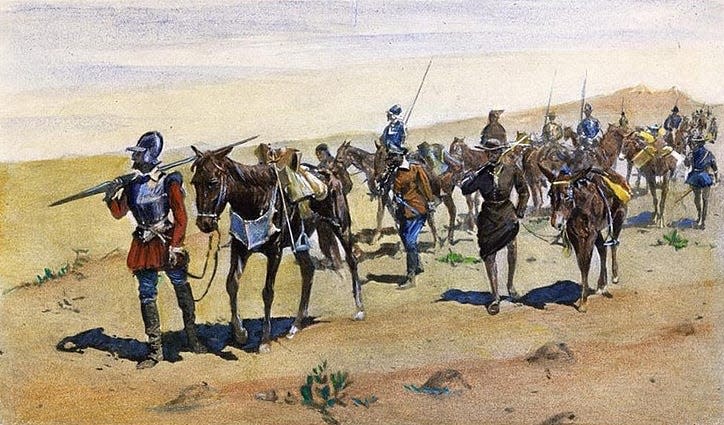

The army was led by Spanish conquistador Francisco Vázquez de Coronado. In 1540, Coronado left the west coast of Mexico with a force of more than 2,000 soldiers, Indigenous allies, Franciscan friars and slaves. In addition to 600 packhorses and mules, the explorers brought a herd of five hundred cattle and a flock of five thousand sheep. It was the first European expedition into what is now the southwestern United States.

In search of the Seven Cities of Cibola, Coronado expected to find a large civilization and great wealth in the form of gold, silver and jewels. Over the next two years, the Spaniards traveled 4,000 miles across northern Mexico and parts of the present states of Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas.

Even today, historians debate the expedition’s exact route. Surviving Spanish narratives indicate the hail storm hit when a large detachment of Coronado’s expedition camped with a friendly Teya Indian tribe in a canyon in what is now the Panhandle/South Plains region of Texas. But which canyon?

There are many canyons in the region, among them Palo Duro Canyon, Tule Canyon, Caprock Canyon, Cita Canyon and Yellow House Canyon. Most maps which have attempted to chart Coronado’s route show the army traveling well north of what is now the South Plains of Texas, and Palo Duro Canyon seems a likely spot for Coronado to have camped. But physical evidence of the expedition has been found in only one canyon of the Llano Estacado.

In the 20th Century, a treasure trove of metal objects was discovered, proving a detachment of about 1800 Spanish soldiers and Mexican Indian allies of Coronado’s expedition camped for a couple of weeks in what is now known as Blanco Canyon in Floyd County.

The Floyd County site yields the first solid archeological proof Europeans visited the South Plains of Texas much earlier than the establishment of historic U.S. settlements in St. Augustine (1565), Roanoke (1584), Jamestown (1607) and Santa Fe (1610).

In the 1950s, Floyd County farmer Burl Daniels, while plowing his land near Blanco Canyon, found numerous Native American artifacts. Daniels once told a reporter the reason his crop rows were so crooked was because “it’s hard to make straight rows and watch for arrowheads at the same time.” But one day, he unearthed something quite different. It was a chain mail gauntlet — a metal glove.

In 1966, Daniels sent the gauntlet to the Texas Memorial Museum in Austin, where museum director W.W. Newcomb Jr. determined the gauntlet was of a type used in Spain, France and Italy from the mid-16th century to the early 17th century. The three-fingered gauntlet was of a style sewn inside a leather glove, to protect the upper hand during sword combat. The sword’s hilt guard protected the other two fingers.

The gauntlet eventually found its way to the Floyd County Historical Museum, but the discovery stirred little attention until other objects began turning up in the 1990s, when the gauntlet served as a catalyst for archeological interest in Blanco Canyon.

The mysteries of Coronado’s route were discussed in about 1990 when New Mexico scholars Richard and Shirley Flint organized conferences on the subject in Amarillo and Canyon. Nancy Marble from the Floyd County Historical Museum brought the gauntlet to the conference and showed it to archaeologist Don Blakeslee.

“At the end of the conference, I was convinced Coronado’s route could not be confirmed,” Blakeslee remembers. On his drive home, Blakeslee had a sort of epiphany. He thought, “To find Coronado’s route, you should look for the best Indian trails, for Coronado would likely have used those trails.” He thought local knowledge could be useful in locating old Indian trails which might turn up evidence of Coronado’s travels.

As Blakeslee expected, Floyd County locals were able to direct him to an ancient Indian trail. Near the trail, just above Blanco Canyon, Burl Daniels’ gauntlet had been found decades earlier.

Meanwhile, Floydada resident Jimmy Owens took his metal detector to Blanco Canyon and started turning up artifacts. "It's like Forrest Gump's box of chocolates down there,” Owens said. “You never know what you're going to get."

Part Two of this series will be published in next Sunday’s Lubbock Avalanche-Journal.

This article originally appeared on Lubbock Avalanche-Journal: Caprock Chronicles: The historic treasures of Blanco Canyon, part one