Canyon County law enforcement decries gang problem. But exactly how big is the issue?

It was a bright June afternoon, and Sgt. Andrew Holmes was on the lookout for gang activity. He’s one of five officers on the Caldwell Police Department’s Operation Safe Streets unit launched in May.

“We’re all very passionate about gang violence in Caldwell,” Holmes told the Idaho Statesman that day. “The guys I work with have spent the last few years working on their skills in that area, getting to know the gang members here in Caldwell — who they are, what they belong to, what they’re doing — investigating graffiti and violent crime.”

Holmes drove around in an unmarked car for the better part of two hours on his gang unit shift. He wound his way through neighborhoods he said were known for attracting graffiti, but nothing was visible that day.

“If we see someone walking around who is obviously dressed up in gang attire, (we will) stop and talk to him, see if he’ll talk to us,” Holmes said.

Holmes said gang attire can be “obvious” — “blue LA hat, solid blue baggy T-shirt” — or “subtle” — “belt hanging down with all black clothes.”

At last, Holmes came to a stop in front of a long, wooden fence covered in spray-painted markings in a residential area. Much of it tagged the area as belonging to either the Norteños or Sureños gangs, though one scrawling phrase used an expletive to call out Child Protective Services. He found it three days earlier but thought it a good example of the type of gang activity he encountered.

“They’re going to be tagging back and forth,” Holmes said. “If we just ignore it, it’ll just grow and grow and be everywhere, and be an eyesore, and make the community feel unsafe.”

Canyon County law enforcement leaders say gangs are a significant enough driver of local crime to justify 11 officers and three units among the Caldwell Police Department, Nampa Police Department and Canyon County Sheriff’s Office dedicated to gang activity. Police press releases out of Canyon County frequently tie the reported crimes to gang activity.

Others in the community worry that such a focus has led law enforcement to mislabel young people as gang members. In fact, the frequently used gang enhancements added to criminal charges are used in plea bargaining and rarely make it to a jury trial.

In a series of public record requests and interviews with law enforcement, the Idaho Statesman found little public information about what standards Canyon County police use when deciding how to categorize gang crime, whether to place someone’s name on a gang list and how many resources should be dedicated to policing gangs.

How significant are the gang-related crimes in Canyon County?

Records obtained by the Statesman show that Caldwell police officers reported 59 gang crimes from June 2022 through May 2023. Among them, 39 were graffiti-related and six were violent crimes.

The Nampa Police Department also said most of the gang-related crime it sees is graffiti. Under Idaho Code, injury by graffiti is a misdemeanor.

“The biggest thing I will tell you about gang crime is graffiti — it’s probably the biggest one that we see influencing areas because it’s all over the Treasure Valley,” Nampa Police Department Lt. Jason Cantrell told the Statesman by phone. “Number two is drug distribution and drug use. And then what goes along with drug use and distribution is you get the burglaries and thefts and so on. And then the fourth thing is the crimes of violence that gang members are involved with, such as drive-by shootings and homicides.”

The Statesman received more than 20 press releases from Canyon County law enforcement in 2023 that mentioned gangs.

“The Nampa Police Department would like the public to know we take gang violence very seriously and have a zero-tolerance stance on gang-related criminal activity,” a Nampa Police Department release titled “Gang Activity in Our Community” stated in January 2023.

Multiple times when asked what information led law enforcement to label someone a known gang member, agencies would not provide additional details to the Statesman.

Caldwell Public Information Officer Char Jackson told the Statesman that police believed a January 2023 incident was gang-related because “the MO (modus operandi) was consistent with gang activity.” Jackson said a man described in an April release was labeled a “known gang member … based on knowledge of the suspect and our investigation.” Jackson declined to elaborate further on both incidents, citing ongoing investigations.

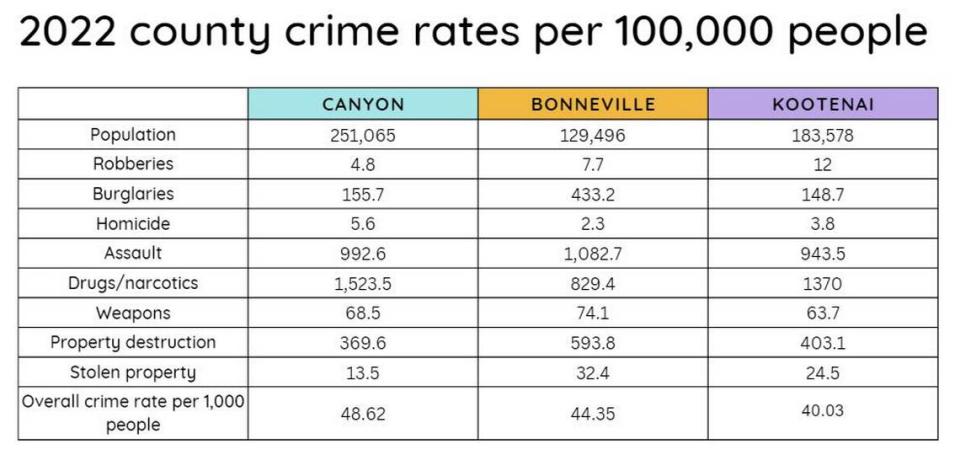

Despite the frequent press releases, Canyon County statistics do not reflect significantly higher rates of the crimes associated with gang activity when compared to Bonneville and Kootenai, the two Idaho counties with the most similar population numbers.

When looking at crimes typically associated with gang members, many of Bonneville and Kootenai’s 2022 crime rates per 100,000 people show numbers similar to or higher than Canyon County’s.

While drug crimes were higher in Canyon, property destruction, weapons crimes, robberies, burglaries, stolen property and assault occurred at rates lower than or similar to those in Bonneville (Idaho Falls) and Kootenai (Coeur d’Alene).

From December 2022 through December 2023, the Statesman reported on five crimes in the Treasure Valley that police said were gang-related.

They included one in December 2022 in which a Caldwell man attacked two supposed rival gang members with a knife at a gas station. Isaiah Magdaleno, who police say is a documented member of the Northern California-based Norteño gang, was convicted and sentenced to 23 years in prison with the possibility of parole after 11 years.

The other crimes were shootings: two drive-by shootings near Caldwell’s Elgin Street and Freeport Street last summer, and two shootings in Boise. One in September injured a girl in an altercation that police said was “gang related,” and the suspect was younger than 18, the Statesman reported. In November, Boise Police said a 31-year-old shot into an apartment complex and called it gang-related — no one was injured.

Despite these frequent news releases describing gang activity, law enforcement provides little information about its gang databases. The Statesman was unable to find out how many people have been labeled gang members by local law enforcement over the years, who is on those lists and the reasons they were placed there. Even those listed as known gang members within local databases might not be aware they are on them.

In 2000s, Canyon County labeled as rife with gang violence

For years, law enforcement labeled Canyon County as an area rife with gang violence, and from 2004 to 2008, Statesman headlines hinted at a rash of gang violence happening in the county.

A 2004 story from the Statesman said that Canyon County was trying to combat its “reputation as a place where gang violence and grudge shootings are routine.”

Police recalled those same years as plagued by gang shootings and violence.

“In 2004 or 2005, we were making national news,” Canyon County Sheriff Kieran Donahue said in an interview. “We were a small area back then.”

The Associated Press also published stories in 2004 about the gang violence in Canyon County.

“The outbreak of violence has brought national attention to the community and raised neighborhood fears about safety,” the AP wrote in November 2004.

In December that same year, the Nampa and Caldwell police had recently finished investigating five gang-related shootings over two months, according to Statesman reporting at the time.

“I am a bit more cautious when I go out at night,” a Caldwell resident told the Statesman in 2004. “And I won’t let my 14-year-old (daughter) go down to the movie theater with her friends anymore.”

Another Statesman report showed city officials and community members in Nampa and Caldwell had numerous meetings to “put an end to the recent streak of gang-related violence.”

Local police officers also wanted to curb the violence, they told the Statesman in recent interviews. They said the Idaho Gang Enforcement Act enacted in 2006 by the Idaho Legislature helped them do that by allowing them to identify people they believed to be in gangs.

It is unclear whether gang crime decreased after the 2006 Gang Enforcement Act, because neither the Nampa nor Caldwell police departments collected gang-crime data before 2022.

“Last year is all that I show for anything marked ‘gang’ in our records,” said Caldwell Records Supervisor Alison Gulley, in an August email. “We only started tracking gang activity in records in the last year.”

Police and community members in Canyon County say they worry gang crime is surging again. But who are the people labeled “gang members” and what kind of threat do they actually pose to the community, and where is that surge?

Who makes the ‘gang list’?

People labeled “gang members” must meet two of the following criteria set in the Gang Enforcement Act:

Admits to gang membership;

Is identified as a gang member by police officers after previous encounters;

Resides in or frequents a particular gang’s area and adopts its style of dress, its use of hand signs, or its tattoos, and associates with known gang members;

Has been arrested more than once in the company of identified gang members for offenses that are consistent with usual gang activity;

Is identified as a gang member by physical evidence such as photographs or other documentation; or

Has been stopped in the company of known gang members four or more times.

Police have touted the law and officials in Caldwell and Nampa claim it allowed them to get a handle on the gang violence of the early 2000s. But Canyon County Latinos and advocacy organizations worried then that non-gang members could be falsely identified.

In 2008, Leo Morales, now the executive director of the ACLU of Idaho, told the Statesman that he was concerned about the racial implications of the law.

“It really has racial profiling written all over it,” he said at the time.

In an October interview with the Statesman, Morales stuck with his feelings from 2008, calling the law “overly broad” and saying it “gives significant power and discretion to law enforcement.”

In a July report by the ACLU, the organization found the Nampa and Caldwell school districts had dress code policies that violated students’ civil liberties, in the name of targeting gang clothing. The dress code policies in the districts targeted many aspects of Latino culture, like wearing Catholic rosaries and “Cholo”-style clothing.

The report found that the dress code policies resulted “in disproportionate discipline of (Latino) students simply for wearing clothing closely tied to their religion, culture and ethnicity.”

Morales said something similar is happening outside of schools in the broader Latino community. He says the “net” that the Idaho Gang Enforcement Act casts is wide.

“It captures individuals that may not even be in a gang,” Morales said. “And that is in part because of how they may dress. It is more related to culture rather than an affiliation with a particular group.”

When Brenda Hernandez, a then-17-year-old at Caldwell High School, wore a “Brown Pride” hoodie to class in January 2023, she saw herself as celebrating her Latino heritage. Her teachers, however, accused her of wearing gang-related clothing.

Hernandez prides herself in her style. She said she wears baggy Dickies pants because that’s what her older relatives wore as Idaho farmworkers in the 1950s. Rosaries draped around her neck represent her Catholic faith. The Brown Pride sweatshirt reminded her of her grandmother.

“My grandma remembers the protests in California with Cesar Chavez and the farmworkers,” Hernandez told the Statesman by phone. “It was a big movement, and people were using the phrases ‘brown pride’ and ‘brown and proud.’”

Hernandez tries not to let negative reactions dampen her love of Chicano — meaning Mexican-American — fashion and the way it connects her to a larger identity. But she has learned that she’s not always in control of what other people see when they look at her. After getting in trouble at school for wearing her sweatshirt, she realized authorities were quick to see clothing worn by Latino students as gang-related, she said.

The ACLU report found that Hernandez was not the only student affected by “discriminatory dress code” policies.

Rules like the one used to target Hernandez are vague and “give schools broad discretion to target and label Latine students as ‘gang,’” according to the ACLU.

The report also found that Latino students faced expulsion at twice the rate of white students in those districts.

That type of inequity may not end once Canyon County students leave their classrooms.

“A couple years ago, individuals who had dice hanging on their rearview mirror, that was enough for a police officer to say, ‘Oh my gosh, this person is in a gang,’” Morales said.

Morales said the Idaho Gang Enforcement Act “targets culture.”

Gang enhancement charges: ‘Great bargaining tool’

The creation of the Idaho Criminal Gang Enforcement Act allowed prosecutors and police to use gang enhancements to add harsher penalties if a crime is connected to gang activity.

Gang enhancements can be added to any charge “knowingly committed for the benefit or at the direction of, or in association with, any criminal gang or criminal gang member.”

Prosecutors can ask for up to a year of additional jail time for a misdemeanor. For a felony, a gang enhancement means a minimum of two additional years and a maximum of five.

The vague wording of gang enhancement laws has been criticized in recent years. In 2021, California legislators voted to significantly restrict prosecutors’ use of gang enhancements after an advisory committee found that 99% of people charged with gang enhancements in Los Angeles County were people of color.

Enhancements are often dropped during the plea bargaining stage in Canyon County, court records show. Prosecutors can offer to drop the enhancement if a person changes their plea to guilty to the underlying charge.

“Evidence of (gang) documentation can have dramatic legal consequences for criminal defendants,” said Joshua Wright, a criminal justice researcher at the Stanford Journal of Civil Rights and Civil Liberties. “One obvious effect is that a felony conviction exposes the defendant to tougher sentences under gang enhancement statutes.”

In Idaho, the county prosecutor’s office decides whether to add an enhancement for crimes that police have flagged as potentially gang-related, Canyon County Prosecutor Bryan Taylor said.

Taylor often sends these cases to Canyon County deputy prosecuting attorney Ellie Somoza, who has been focused on gang crimes in Idaho since she joined the office 18 years ago. She successfully helped lobby the Legislature to increase the amount of time added to a felony through gang enhancements and says they are an effective deterrent. In 2007, legislators changed the law, making it so those convicted of felonies with a gang enhancement, who had previously faced a term of up to two years, would face a minimum of two years.

“I use the gang enhancement a lot because it’s great,” Somoza said. “It’s a great bargaining tool for us, and it’s a great enhancement. If we go to trial and I get a conviction, then the judge has to impose prison time.”

More often, however, those with gang enhancements enter into plea bargains.

In Canyon County, 41 people were charged with gang enhancements between January 2018 and May 2023. Thirty-eight of those cases were provided to the Statesman without redactions of the outcomes. Of those 38, zero people were found guilty with gang enhancements. The majority of enhancements were dropped in the plea bargaining stage.

Community leaders report signs of gang uptick

In Canyon County, community members say they worry that gang activity is increasing.

The Caldwell School District is strict with its dress code policies surrounding possible membership. When asked about the ACLU report, Jessica Watts, district spokesperson, sent the Statesman a list of articles related to gang activity and said “the gang issues in our area are increasing and more covert.”

C.J. Watson, administrator at Elevate Academy, a career technical school with locations in Nampa and Caldwell, said gang member recruiting is increasing like it was in the early 2000s.

“All the big hitters were in jail in the past year or two and they’ve all been getting out,” he said from his office at the Caldwell school location. “There’s been a high level of recruiting picking up. We’ve even seen it pick up within our building.”

Elevate Academy serves “at-risk” Idaho youth. The criteria to determine if a student is “at risk” is codified in Idaho law. Watson says Elevate defines at-risk students as “students that have potential that has not been tapped in a traditional education setting.” Some of their students were previously part of gangs or are current gang members, he said.

Watson said downtown Caldwell’s redevelopment is pushing a lot of the city’s Latino population out in order to cater to a whiter, wealthier Idahoan.

“You have gentrification happening in Caldwell, which is further isolating groups,” he said. “The type of gentrification happening is focusing on one demographic of Caldwell and not the whole, which is adding to them feeling like they don’t belong in society.”

Mike Dittenber, executive director of the Caldwell Housing Authority, said the complex often sees signs of gang crime before the broader community. He sees graffiti on the outside walls of the housing authority, or at the bus stop or picnic tables. He said the graffiti is a sign that gang members are claiming their territory.

“We are a micro-community of the larger Canyon County area,” he said in a phone interview.

Dittenber said the Housing Authority has a history of being the setting of gang fights. He also said they no longer have a tolerance for graffiti.

But Dittenber said labeling Caldwell as the city in Idaho with the most gang activity is unfair. He said the city has that reputation because of its population breakdown. It has the highest concentration of Latinos in the valley, at over 25%.

He added that as the county sees an increase in gang recruitment, people shouldn’t hide. He encourages the county to be more open and friendly in order to combat gang membership.

“I just wish that there was a time where we could say, ‘Community gangs are a community issue and it’s not a law enforcement problem to solve, it’s a community problem,’ ” Dittenber said.

Ada County places smaller emphasis on gang policing

Not all Boise-area law enforcement agencies place the same emphasis on gangs as Canyon County agencies.

Caldwell has five full-time employees in its Operation Safe Streets unit and the Nampa Police Department also has five in its gang unit. The Canyon County Sheriff’s Office has one full-time detective on the Treasure Valley Metro Violent Crime Task Force, a unit comprising multiple police departments in the valley, the FBI and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives — all dedicated to reducing gang violence in the area.

Two additional Canyon County detectives and a sergeant are on the City-County Narcotics Unit, a collaborative effort between the Nampa Police Department and Canyon County Sheriff’s Office that often assists with gang crimes.

Last year, Caldwell Police Chief Rex Ingram disbanded its Street Crimes Unit after former Caldwell police officer and unit leader Joey Hoadley was convicted in a federal case and sentenced to three months in jail. Hoadley punched someone while on duty and falsified and destroyed records about the encounter. Ingram told the Statesman that Ryan Bendewald, another former Caldwell Police officer who was indicted on seven felony charges related to abuse of power and using his law enforcement position to “sexually victimize women,” was also on the Street Crimes Unit.

“The issue was that when allegations of misconduct or use of force were alleged, they weren’t reported,” Ingram told the Statesman in an interview in August. “The (former) chief and the captain were just disconnected from it.”

Last August, Ingram relaunched and rebranded the gang unit as Operation Safe Streets. He told the Statesman then that he was watching it closely.

“I’m looking at everything,” Ingram said. “Part of that is implementing the (log), which is a daily activities report of everything they’re doing. I see it every day.”

The Ada County Sheriff’s Office has one full-time deputy dedicated to gang policing.

The Boise Police Department had a gang unit for 28 years — until 2021, at which point all members were moved to other areas because of staffing shortages, Boise Police Chief Ron Winegar said.

In May, Winegar decided to bring back that unit on a temporary basis by pulling five officers from other areas of the department. Capt. Jim Quackenbush, who spent two decades as a gang officer in Portland, led the group.

The police chief was hesitant to define the unit’s necessity or lack thereof. While the officers focused on gang-related activity, they continued to police the city in a number of other ways. Winegar said he preferred to think of the city’s policing needs as fluid.

“We have to continually analyze and move resources where we need them the most at the moment,” Winegar said.

The decision to relaunch the Boise gang unit was spurred by an “uptick in juvenile crime” near the Boise Towne Square mall, Winegar said. Some of those juveniles were documented gang members, Winegar said.

“Last spring, we had a group of young people that were engaged in thefts and very low-level robberies, vandalisms, things like that,” Winegar said. “But it was enough of a concern that it was hitting the radar. We were getting regular calls for service at that location.”

Quackenbush said his officers were able to successfully lower the number of juvenile crimes by doing regular patrols of certain high-traffic areas at night, including the mall and downtown.

Ultimately, the gang unit lasted three months. Winegar disbanded it in September, saying he had decided the officers’ time would be better spent elsewhere.

“We are always responding and planning and trying to allocate the precious resources we have in the best places so that we can have the best effect for the community,” Winegar said. “And really, what it’s about, is making sure, number one, our community is safe. And number two, our community feels safe.”

When it comes to gang policing, Quackenbush stressed the importance of “push(ing) our resources towards problems that are backed up with data.” He and other officers plan to use the information they collected on juvenile crime over the summer to figure out the best strategies to prevent possible gang activity from rising in the first place, including strengthening ties to the community.

“What I would hate to see is a knee-jerk reaction,” Quackenbush said. “Where you have violence erupting or you have gang problems, too many agencies have had the experience where then they just grab a group of officers, and then they just throw them at the problem. And then they’re a little bit shocked and surprised when something bad or controversial happens, because they have no training. They have no relationships in the communities with the people that they’re interacting with.”

The way to resolve the disconnect when it comes to policing gangs, Morales said, is greater transparency from the agencies.

“We should be able to have a policy debate about the process of how someone gets on (the gang list), how someone gets off,” Morales said. “At the end of the day this has real consequences on people’s lives, and with government secrecy, this is a dangerous space for every Idahoan regardless of who they may be.”