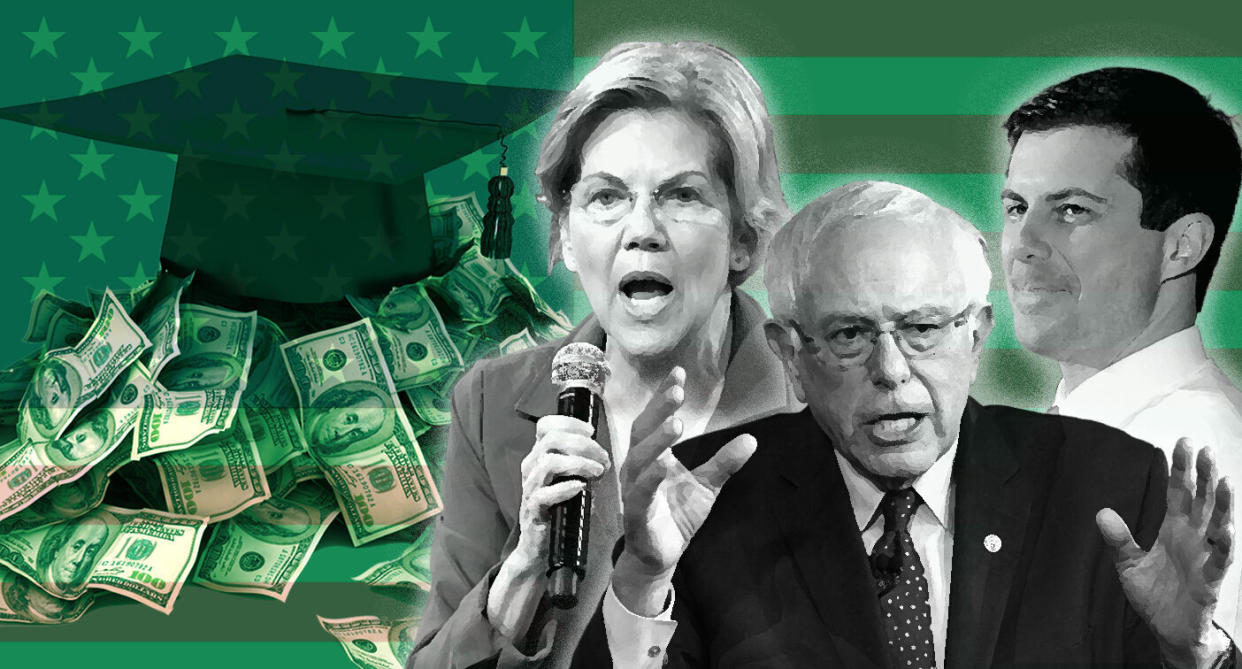

Candidates tackle student-debt crisis

Presidential elections are decided by many things: media exposure, financial backing, personal chemistry, timing and luck. Policy positions often are just a way of signaling where a candidate stands on the political spectrum. But 2020 is shaping up to be different, the most ideas-driven election in recent American history. On the Democratic side, a robust debate about inequality has given rise to ambitious proposals to redress the imbalance in Americans’ economic situations. Candidates are churning out positions on banking regulation, antitrust law and the future effects of artificial intelligence. The Green New Deal is spurring debate on the crucial issue of climate change, which could also play a role in a possible Republican challenge to Donald Trump.

Yahoo News will be examining these and other policy questions in “The Ideas Election” — a series of articles on how candidates are defining and addressing the most important issues facing the United States as it prepares to enter a new decade.

Generations of younger Americans are struggling under the weight of ever-more-unaffordable student debt — and dragging down the U.S. economy as a result.

Consider a few statistics. Today, nearly 70 percent of college graduates leave school in debt. On average, they owe about $30,000; many owe $100,000 or more. And they’re not alone: 44.5 million Americans now face the same burden, and together they’re on the hook for $1.57 trillion — or half a trillion more than all U.S. credit-card debt combined.

That’s a staggering amount of money: about 7 percent, in fact, of the total federal debt. It wasn’t always thus. Just 10 years ago, America’s overall student-debt burden was $675 billion; 10 years before that, it was less than $100 billion.

Several factors have conspired to create the current crisis: middle- and working-class wage stagnation; plummeting state investment in public higher education; massive hikes in tuition and fees; the rise of private, for-profit colleges; and a government that has encouraged students to cover the soaring cost of college by taking out loans they likely can’t afford.

But whatever the causes, the effects of today’s crushing student-debt load are clear. It’s reducing home ownership rates among millennials. It’s leading fewer young people to start businesses. It’s forcing students to drop out of school before getting a degree. And every year, according to one recent study, it’s effectively reducing the GDP by as much as $108 billion and costing the U.S. economy as many as 1.5 million jobs.

No wonder nearly half of indebted millennials say college wasn’t worth the expense, and 68 percent say they worry about debt every day.

No wonder, too, that nearly all of the 2020 Democratic presidential contenders say they want to fix the problem.

To get a sense of just how bad the student-debt situation has become, it’s worth looking back at how exactly we got here.

Student loans are a fairly new phenomenon. They didn’t formally exist in the U.S. before 1838, when Harvard began offering interest-free loans to less-affluent students, and they didn’t become public policy until more than a century later. During World War II, the government made its first foray into college financing with the GI Bill, which subsidized or covered the cost of higher education for nearly half of America's returning veterans.

In 1958, amid fears of losing the “space race” to the Soviet Union, Congress passed the first federal U.S. loan program, the National Defense Education Act, which provided loans to a limited pool of students in scientific and technical fields. In 1965, the Higher Education Act first offered federal loans to students regardless of their field of study, and subsequent versions of the law further broadened access. The basic idea was that the United States could no longer afford to “waste brainpower”; instead, the government should help young Americans get a college degree regardless of whether they could afford to pay their own way.

For the next couple of decades, the new system seemed to work relatively well. But as more and more students chose to pursue a higher education, alarm bells began to sound. “Experts ... say that record borrowing for college threatens the financial stability of a generation of young people and their families,” the New York Times reported in 1987. “With college costs rising and the number of grants declining, students and their parents last year took out nearly $10 billion in federal education loans.”

The crisis deepened in the 1990s. States started to slash funding for public higher education, and tuition at public universities skyrocketed. Growing demand for admission, the need to hire more faculty, expanded student services, and near-universal access to loans sent private tuition soaring as well. Meanwhile, Congress steadily raised borrowing limits and cracked down on delinquent debtors by making it harder to discharge student loans through bankruptcy. As lower- and middle-class wages stagnated — the bottom 90 percent of the population hasn’t pocketed a single cent of America’s overall income growth since 1997 — college students and their families began to take on increasingly unsustainable (and inescapable) levels of debt.

The result? Federal loans no longer total $10 billion a year; in 2018, they hit the $122 billion mark. The average loan for a college graduate is no longer the $9,000 it was in 1993; now it’s three times that amount. And while slightly fewer than half of college graduates owed money back then, seven out of 10 do today.

As president, Barack Obama put in place a few modest reforms, including debt relief for defrauded students (which the Trump administration tried to derail). But the 2020 Democratic candidates are thinking bigger.

Their proposals fall into two broad categories: 1) help for people currently struggling with student debt and 2) reforms that will shield future generations from debt crises of their own.

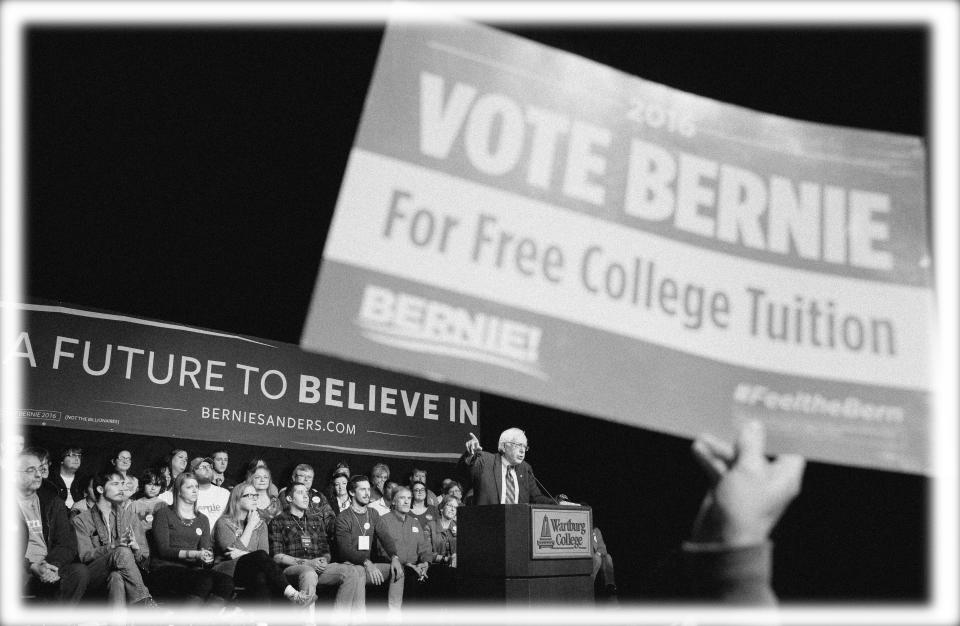

Most candidates are focusing on the latter approach, notably Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders. More than anyone else, Sanders has been responsible for ushering the idea of free public college into the mainstream. During his insurgent bid for the 2016 Democratic presidential nomination, he proposed tuition-free public college for all through a partnership between the federal government, which would fund two-thirds of the cost, and the states, which would fund the rest.

At first, his rival Hillary Clinton opposed the idea, arguing that the Sanders plan would result in “taxpayers … paying to send Donald Trump’s kids to college.”

“My late father said, ‘If somebody promises you something for free, read the fine print,’” Clinton snapped at the time.

Eventually, though, Clinton adopted something like Sanders’s position — with one important tweak. Instead promising to cover public-college tuition for everyone, she limited the program to families making $125,000 or less.

After the election, Sanders followed Clinton in introducing a bill that would also restrict tuition-free public college to families earning $125,000 or less (while making community college free for everyone). The Sanders campaign has yet to unveil a 2020 proposal, but his 2017 bill is likely to serve as the blueprint.

The rest of the field, meanwhile, seems to be heading in the same direction. Rep. Tulsi Gabbard of Hawaii co-sponsored the House version of Sanders’s College for All Act. Rep. Eric Swalwell of California, a 38-year-old who often notes that he’s still paying back the roughly $150,000 he borrowed to attend college and law school, wants create a path to debt-free public college for students who do work study and commit to serving their communities after college. In a town hall appearance in South Carolina last month, Rep. Beto O’Rourke of Texas told supporters that students who go to public four-year universities should be able to go for free.

“We need to commit to 16 years of free public education for all our children,” former Vice President Joe Biden told reporters in 2015. “We all know that 12 years of public education is not enough. As a nation, let’s make the same commitment to a college education today that we made to a high school education 100 years ago.”

Others may go in a more nuanced direction. In March 2018, Hawaii Sen. Brian Schatz introduced his Debt-Free College Act, which differs from Sanders’s original proposal in that it wouldn’t cover public-college tuition at all income levels, but also from Clinton’s, in that it would cover ancillary expenses, such as room and board, as well as tuition.

That’s because “we ought to cover the full cost of college for people who can’t afford it before we cover tuition for people who can,” Schatz explained.

Sens. Kirsten Gillibrand of New York, Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, Kamala Harris of California and Cory Booker of New Jersey all co-sponsored Schatz’s bill.

“We need a national priority and commitment to debt-free college, which I support,” Harris said in a recent CNN town hall.

And then there’s the other half of the equation to consider: What to do about all the Americans already drowning in student debt?

A few candidates — O’Rourke, Gillibrand, Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar, South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg — have already seized upon the perennial Democratic solution: Allow federal student loan borrowers to refinance their debt at lower interest rates.

But with critics noting that “any student-loan refinance plan would disproportionately benefit borrowers with the most debt, who are more likely to have attended graduate school and, therefore, make a decent living,” as MarketWatch’s Jillian Berman recently put it, at least three Democrats have argued that the government should simply cancel student debt instead.

Two of these candidates — tech entrepreneur Andrew Yang and Miramar, Fla., Mayor Wayne Messam — barely register in the polls. In his late March announcement speech, Messam, a 44-year-old former college football player, put student debt front and center, saying that if elected he would push for national student debt forgiveness. And while Yang hasn’t gone quite that far, he is open to exploring various forms of principal reduction and loan forgiveness.

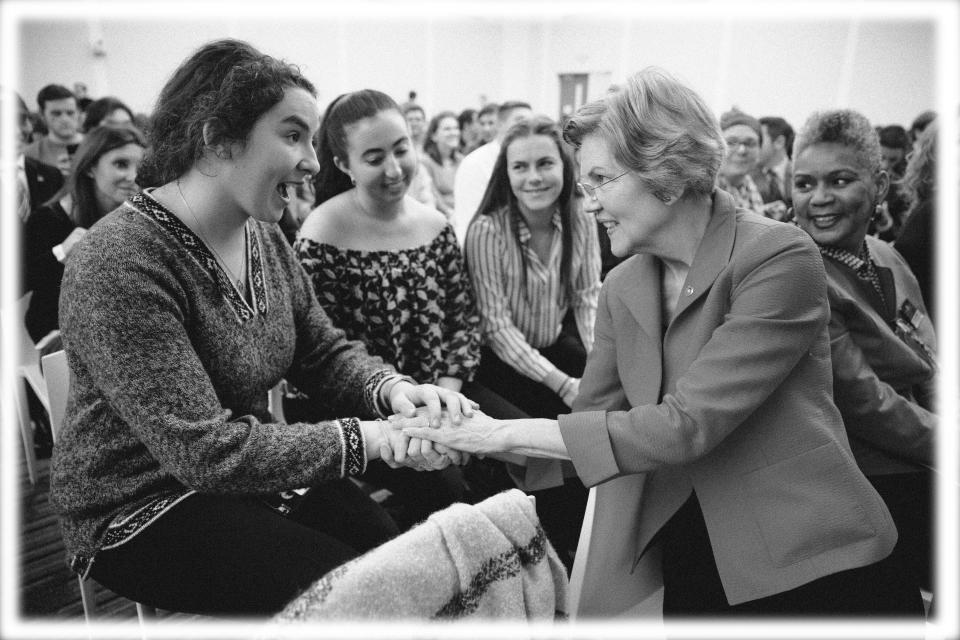

Yet by far the highest-profile proponent of student-debt cancellation is Elizabeth Warren. In April, Warren introduced a college affordability plan. One half was fairly familiar: eliminating the cost of tuition and fees at every public two-year and four-year college in America while expanding Pell Grants by $100 billion over the next 10 years to cover nontuition expenses and give lower-income and middle-class students a better chance of graduating without debt.

The other half broke new ground: a broad debt-cancellation plan that would provide at least some relief for 95% of people with student-loan debt — roughly 42 million people — according to an economic analysis conducted for Warren’s campaign.

Unlike previous proposals, which would have provided a disproportionate benefit to (likely wealthier) borrowers with large debt loads, Warren’s plan attempts to be progressive. Make less than $100,000? You get $50,000 in student-loan debt relief. Make between $100,000 and $250,000? You get some of your debt erased (i.e., $1 for every $3 in income above $100,000). Make more than $250,000? Sorry — no debt cancellation for you.

“The time for half-measures is over,” Warren wrote in her policy announcement on Medium. “My broad cancellation plan is a real solution to our student debt crisis. It helps millions of families and removes a weight that’s holding back our economy.”

Complicated, to say the least. Republicans have occasionally acknowledged the student-debt crisis and gestured at policy solutions, with Florida Sen. Marco Rubio taking the lead; last week, he introduced legislation that would eliminate interest on federal student loans in favor of a one-time financing fee that would be paid over the life of the loan and not accumulate with age. Even Donald Trump has addressed the issue, proposing a fairly liberal repayment plan during the 2016 campaign. But as president he never followed through, and in 2020, Republicans are likely to assail any of the bolder Democratic proposals as a) too expensive and/or b) fundamentally unfair.

“Elizabeth Warren's plan to cancel student loan debt would be a slap in the face to all those who struggled to pay off their loans,” wrote conservative columnist Philip Klein at the Washington Examiner, summing up the view from the right. Even worse, “paying off student loans would be another signal from the federal government that those who may be engaging in less responsible behavior will eventually be bailed out by government while those who make responsible decisions will receive no benefit.”

Yet the biggest challenge facing a plan like Warren’s isn’t that it’s unfair in the abstract — it’s that although Warren aims to be progressive, she may still be subsidizing what Michael Strain of the conservative American Enterprise Institute calls “the comfortable class.”

“Aside from all the ways such a plan would provide incentives to enterprising people to game the system and to colleges to inflate costs even more than they already do, there’s a larger principle here: The U.S. needs to spend less public money on households earning comfortable incomes, not more,” Strain explains.

Liberal columnist David Leonhardt of the New York Times agrees, calling Warren’s plan “too bourgeois.”

“It confuses the mild discomforts of the professional class with the true struggles of the middle class and poor,” Leonhardt writes. “A 24-year-old in Silicon Valley making $90,000 — and on a path to earn far more — could get a windfall. And people earning up to $250,000 — say, a 27-year-old investment banker or corporate lawyer — would get some benefit from the plan.”

The politics of free college are similarly fraught. A 2016 Gallup poll, for example, found that “less than half of Americans — or just 47 percent — supported the idea of tuition-free college,” and that it was “especially unpopular among the white working-class voters who flocked to Donald Trump and whom Democrats are now working hard to court.” The reason? Blue-collar voters assumed that only elites would benefit from the policy.

Many Democrats hope a needle-threading proposal such as Schatz’s can solve this tricky political problem. But not all of the party’s 2020 candidates are convinced.

“I wish,” Amy Klobuchar replied when asked at a February CNN town hall if she supports the idea of free college. “If I was a magic genie and could give that to everyone and we could afford it, I would.”

“Americans who have a college degree earn more than Americans who don’t,” Pete Buttigieg added during an April event at Northeastern University in Boston. “I have a hard time getting my head around the idea of a majority who earn less because they didn’t go to college subsidizing a minority who earn more because they did.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: