One Democrat has a plan to run against Trump on immigration

Presidential elections are decided by many things: media exposure, financial backing, personal chemistry, timing and luck. Policy positions often are just a way of signaling where a candidate stands on the political spectrum. But 2020 is shaping up to be different, the most ideas-driven election in recent American history. On the Democratic side, a robust debate about inequality has given rise to ambitious proposals to redress the imbalance in Americans’ economic situations. Candidates are churning out positions on banking regulation, antitrust law and the future effects of artificial intelligence. The Green New Deal is spurring debate on the crucial issue of climate change, which could also play a role in a possible Republican challenge to Donald Trump.

Yahoo News will be examining these and other policy questions in “The Ideas Election” — a series of articles on how candidates are defining and addressing the most important issues facing the United States as it prepares to enter a new decade.

Three years into the presidency of Donald Trump, who launched his campaign with a call to crack down on illegal immigration from Mexico and Central America, the United States is on track to see the largest number of migrants arriving at the southwest border without proper documentation in more than a decade.

But more important than the totals, which remain well below the historic rates of illegal border crossings reported during the late 1990s and early 2000s, is the demographic makeup of the migrants.

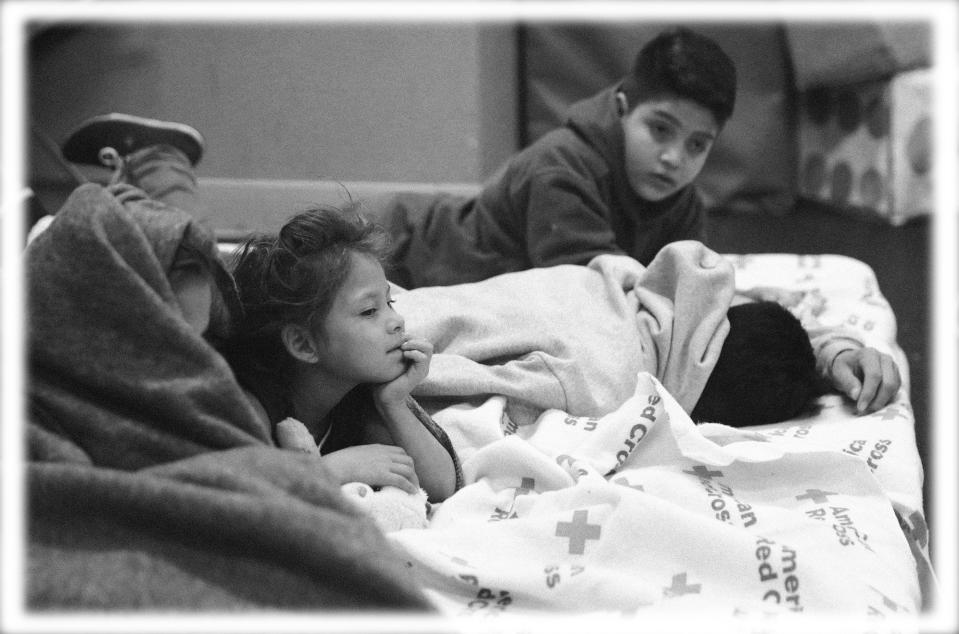

During the month of September 2018, Border Patrol agents arrested 16,658 people caught illegally crossing the border with a family member — ending the fiscal year with what was, at the time, the highest monthly total of family unit apprehensions to date. Since then, arrests of families between official ports of entry on the southwest border have continued to climb to historic highs each month, with significant spikes in February (36,531) and March (53,077) and another big jump last month to over 92,000, a 12-year high.

Families and unaccompanied children — mostly from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador — now make up a majority of migrants arriving at the southern border without documentation, supplanting single adult males from Mexico.

But unlike single men, families and children arriving at the border to request asylum cannot be quickly deported after arrest. Border officials have found themselves ill-equipped to accommodate this new population in facilities that were designed for single men.

Beyond the border, the United States is home to an estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants, 66 percent of whom had been in the country for more than 10 years as of 2016 and who, because of Trump administration’s aggressive enforcement policies, are increasingly vulnerable to the threat of deportation.

More than 50,000 immigrants are in detention, a record high, with ICE actively searching for more space to house detainees.

Although the crisis has been shaped by Trump’s immigration policies, its origins can be traced to legislation that dates from well before the current administration.

Much of the legal framework for today’s immigration system is rooted in the Immigration and Naturalization Act, or INA, of 1965, which eliminated discriminatory country-based quotas that favored immigrants from Western Europe in favor of a system that prioritized family reunification and, to a lesser degree, employment-based immigration.

The law helped create the diverse, multicultural immigrant population that has changed the makeup of the United States — legally and illegally — over the last half-century.

In 1996, President Bill Clinton signed another immigration overhaul that laid the groundwork for today’s deportation and border enforcement system.

The changes made it easier for the U.S. to deport people, and made more people eligible for deportation, while also making it significantly harder, if not impossible, for immigrants already in the country unlawfully to obtain legal status. Deportations skyrocketed after 1996, as did the undocumented population in the U.S.

After the terror attacks of September 11, 2001, new laws and policies greatly expanded the immigration enforcement crackdown set into motion by the 1996 law, a trend that continued through the Obama administration and has accelerated under Trump.

Among the changes were the expansion of immigration detention and expedited removal, the use of criminal penalties against some border crossers and restructuring the Border Patrol and Immigration and Naturalization Services to become part of the newly established Department of Homeland Security. These moves officially conflated the missions of immigration and border enforcement with counterterrorism and national security.

Meanwhile, Congress, the White House and the courts have wrestled for years over how to treat Dreamers — people who immigrated illegally to the U.S. as children — an issue that was caught up last year in the debate over Trump’s request for funding for a wall on the border with Mexico.

While many the Trump administration’s immigration policies have been widely condemned by Democrats, most of the 2020 presidential candidates have held back from presenting specific plans for reform.

In fact, of the 20 candidates currently crowding the 2020 Democratic primary field, just one so far has produced a detailed policy proposal on immigration: Julián Castro. On April 2, the former San Antonio mayor who served as secretary of housing and urban development under President Obama unveiled his “People First Immigration Policy.”

Castro’s ambitious proposal includes many standard Democratic positions, including a pathway to citizenship for Dreamers, for refugees with “temporary protected status” because they would be in danger in their homelands, and millions of others living in the U.S. without protection or other options for legal status. He pledged to undo a number of Trump administration policies, including the ban on entry for citizens of majority-Muslim countries and barriers to asylum seekers. He would reverse Trump’s large cuts to refugee quotas and expand the qualifying categories “to account for new global challenges like climate change.”

Castro’s proposal also includes bold reforms to the broader immigration system, starting with a repeal of the law that treats crossing the border without authorization as a federal crime rather than a civil violation. This statute, he notes in his proposal, “has allowed for separation of children and families at our border, the large-scale detention of tens of thousands of families, and has deterred migrants from turning themselves in to an immigration official within our borders.”

He also seeks to eliminate the private immigration detention and prison industry, and drastically reduce the population of detainees. He proposes restructuring U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) into two separate agencies, one tasked with general immigration enforcement and another focused on investigating terrorism, drug and human trafficking, an idea supported by many ICE officials in a letter sent last year to then-DHS Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen.

Looking beyond U.S. borders, one section of Castro’s proposal outlines a plan for “Establishing a 21st Century ‘Marshall Plan’ for Central America,” to improve conditions in the countries from which refugees are fleeing.

Asked why he chose to dive head first into immigration at this early stage in the campaign, Castro told the New Yorker’s David Remnick, “I wanted to go as straight to what this President has considered his bread-and-butter issue. This is how he stokes division.”

Other candidates have been more hesitant to take the plunge.

Before entering the race, former Rep. Beto O’Rourke seemed to be positioning himself as Trump’s most formidable adversary on border and immigration issues, especially on the construction of a border wall. When Trump traveled to El Paso to speak about the border wall earlier this year, O’Rourke held a counter rally, proclaiming, “We are not safe because of walls but in spite of walls.” In a post on Medium, he listed 10 “immigration, security and bilateral policies that match reality and our values,” including increasing visa caps, and investing in additional infrastructure and personnel at the ports of entry along the U.S.-Mexico border to combat drug and human trafficking.

As a presidential candidate, however, O’Rourke has been light on specifics. At a town hall in San Diego this week, O’Rourke talked loosely of “comprehensive immigration reform” that would include a pathway to citizenship for millions of undocumented immigrants, including Dreamers and their parents.

While Bernie Sanders hasn’t shied away from the immigration debate, he hasn’t offered much in the way of new ideas on the issue.

During a Fox News town hall on April 16, Sanders expressed support for “comprehensive immigration reform,” and called for hiring “hundreds of new judges” to more quickly clear up backlog of more than 800,000 pending immigration cases. He also endorsed “building proper facilities right on the border” for the surge of families in custody.

Demonstrating the sensitivity of the issue, though, Sanders, speaking in Iowa last month, denied he was "an advocate for open borders,” an accusation Trump regularly lobs at Democrats.

"If you open the borders, my God, there’s a lot of poverty in this world, and you’re going to have people from all over the world,” Sanders said, once again calling for “comprehensive immigration reform.”

Meanwhile, candidates such as Kamala Harris and Cory Booker are working on immigration issues in Congress, rather than on the campaign trail. Harris, the California senator and daughter of immigrants, who has made clear that she intends to court Latino voters, has introduced legislation to expand oversight of ICE detention facilities. She said she plans to introduce a bill with Sen. Richard Durbin, D-Ill., to allow Dreamers to serve as congressional staffers.

This week in the Senate, Booker took the lead to re-introduce Dignity for Detained Immigrants Act, an ambitious bill to drastically undo the country’s vast immigration detention system in response to the Trump administration’s latest efforts to expand it.

Castro’s proposal was praised by immigration advocates, who have long been pushing for Democrats to push back harder against Trump on immigration issues. Some predicted Castro’s plan would be the catalyst to force other Democrats to offer clear proposals of their own, though thus far no one has really followed suit. The question now is how long the other Democrats can avoid taking a strong position on what will surely be a central issue of Trump’s 2020 campaign.

In the 2018 midterms, Democrats generally steered clear of the topic, focusing instead on issues such as health care and taxes, while many Republicans copied Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric and his efforts to stoke fear about migrant caravans.

The result, a historic gain for Democrats in the House of Representatives, appear to have vindicated that strategy.

But the politics might play out differently in a presidential election, when Trump himself is on the ballot.

According to a Washington Post-ABC News poll released this week, Democrats are growing increasingly concerned about illegal immigration at the southwest border, with 24 percent now agreeing that the situation is a “crisis,” compared to 7 percent who felt that way in January.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: