Can affirmative consent apps combat campus sexual assault?

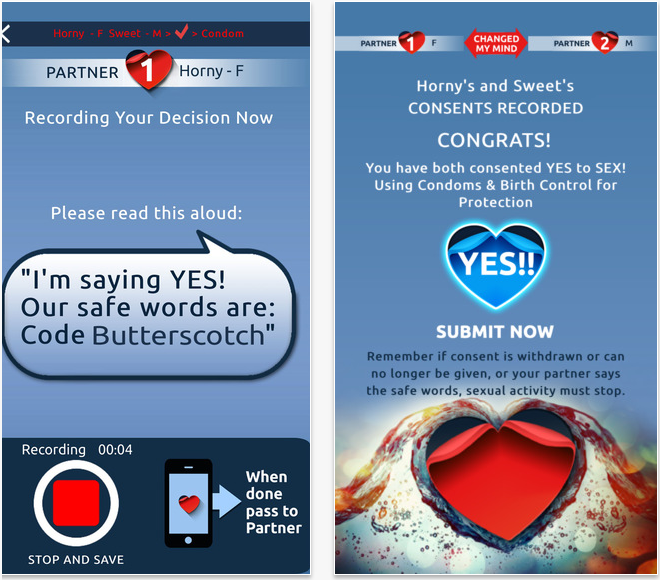

The creators of YES to SEX, a smartphone app that promises to help “all gender partners get and give a safe sexual consent in as little as 25 seconds,” have released a new platform that allows colleges and universities to customize the application to meet the specific needs of their campuses.

Like the original version of YES to SEX, YES to SEX EDU prompts each partner to select their gender, a word that best describes their sexual mood, and their preferred method of birth control, before instructing them to record themselves saying “Yes!” along with an agreed-upon safe word.

YES to SEX founder Wendy Mandell-Geller told Yahoo News that after launching the original version of the app in April, she soon realized its potential to make an impact on university and college campuses.

“We decided to launch at the end of the school year, because universities are creating and getting approval on their fall programs,” she said.

In addition to providing users with an up-to-date guide to giving and receiving sexual consent under Title IX, the app’s new college format can be customized to reflect each school’s policies — as well as its color scheme.

“Every school is different, so every YES to SEX EDU app will be slightly different and customizable,” Mandell-Geller said. “Knowing this, we plan to work with universities and colleges to tailor the app to their needs, demographic and problem set.”

YES to SEX, and now YES to SEX EDU, are part of a new class of tech products that have emerged in the past few years in response to increasing reports of rampant sexual assault on college campuses.

The first app that attempted to tackle this taboo topic with tech launched in September 2014. Cleverly dubbed Good2Go, the app attempted to clear up potential confusion over consent by prompting would-be partners to start by answering a series of questions to determine whether or not they were both, well, good to go.

Good2Go was met with harsh criticism upon its release.

“It goes without saying that barely anyone will use this tool, because there is probably no better way to kill the mood than opening up an app on your phone and shoving it in the face of the person you want to have an intimate human experience with,” Yahoo Tech’s Alyssa Bereznak wrote at the time.

“But the fact that this app exists proves something much more important: that people out there very wrongly think that sexual consent can be granted by something as simple as pressing a button on a phone.”

Good2Go was available in Apple’s App Store for just nine days before it was pulled from digital shelves, reportedly for violating the company’s rule against “excessively objectionable or crude content.”

In the meantime, other apps including YES to SEX have cropped up in its place. Last summer, the Florida-based Institute for the Study of Coherence and Emergence (ISCE) released a suite of apps under the name We-Consent.

In addition to the original We-Consent app, which allows both partners to record encrypted video statements of affirmative consent, the suite also includes three other apps. “What-About-No,” aims to help users take a tougher stance against unwanted sexual advances by playing a video of a policeman saying “No” for their partner and recording an encrypted video of them watching it.

“I’ve Been Violated,” lets victims record details and evidence of their sexual assault on a video that will be saved until they choose to file an official report. The “Party Pass” app aims to promote safe and responsible partying behavior. By using the app to scan a code displayed at the entrance to school-sanctioned parties, students pledge to “not engage in sexual relations for the next eight hours unless I have an explicit discussion about them with my prospective partner first.”

Like the new YES to SEX EDU, the We-Consent apps are designed with college campuses in mind.

“Individuals can help themselves, but they can’t really effect change,” said Michael Lissack, director of the ISCE and founder of We-Consent.

While the technology seems to have improved since the launch of Good2Go, the big question is still whether apps like these can be effective. The expert opinions are mixed.

Neena Chaudhry, director of education and senior counsel at the National Women’s Law Center, which works to enforce Title IX, said she thinks “anything that helps a student get clear consent is a good thing.”

Mahroh Jahangiri, deputy director of the anti-sexual violence advocacy group Know Your IX, argues that “Consent apps like YES to SEX and We-Consent only expand the problem of campus sexual assault.”

“These apps focus on a dangerously narrow understanding of verbal consent — one that disregards the coercive context in which it may be given… and the ways in which consent might be offered, exist for part of [a] sexual act but not others, or more importantly, withdrawn,” Jahangiri told Yahoo News.

“There are other ways to inspire conversations around healthy sex that do not ignore — and at worst, legally undermine — the many survivors who may have been assaulted after withdrawing consent, who have experienced intimate-partner violence, and those who said ‘yes’ under the influence of substances or other coercion,” she continued. “Instead of these ill-informed apps, schools should focus on implementing well-known best practices for better transparency and encouraged reporting.”

Sharyn Potter is an associate professor of sociology and co-director of a research unit called Prevention Innovations, Research and Practices for Ending Violence Against Women on Campus at the University of New Hampshire. She isn’t completely opposed to the idea of using apps to facilitate conversations around consent, but she said she does worry about the potential for coercion, or for even legitimate recordings to be used against victims later, if an assault does occur.

“If somebody does get assaulted because one person thought they were just going take off their shirt and the other person thought they were going have sex, I’m nervous the person who just wanted to take off their shirt wouldn’t report the rape, because she was recorded saying yes to the event,” Potter said.

“By having this ‘yes’ on video,” or on an audio file, Potter added, “it might make some more comfortable or give them a get-out-of-jail-free card.”

Still, she said, that doesn’t mean apps can’t help combat sexual assault. She pointed to another app called Callisto as an example of a successful use of the technology. Developed by the nonprofit Sexual Health Innovations and currently being studied on college campuses, Callisto lets victims save time-stamped sexual assault records that are only reported to a school’s Title IX coordinator if another student records an assault by the same perpetrator.

Both Lissack and Mandell-Geller see their apps as part of a larger social movement toward changing attitudes and behavior around sex and sexual assault.

“As a mother of three, an entrepreneur and an activist, I created the platform to empower people to speak up for his or her sexual health,” Mandell-Geller said. “When paired with a customized strategy, the platform teaches and empowers students to speak up. My goal is to be the one-second reminder that can change the course of any student’s life.”

Similarly, Lissack said he hopes to both “empower victims” and “evoke conversation” with his apps, but acknowledges that social change cannot be mandated or created overnight.

The “problem with this topic is people keep thinking about it as if it has easy, one-step solutions, but there are no easy one-step solutions,” said Lissack. “It’s like a vaccine. You don’t need 100 percent compliance, you just need something over 60 to 70 percent, and after that, the community effect works.”

Whether that community effect can be achieved remains to be seen. At this point, YES to SEX EDU and We-Consent remain in the pilot stages, though both Mandell-Geller and Lissack said they’re working on securing partnerships with colleges and universities ahead of the next school year.

“I think in theory it could be helpful,” said Chaudhry. “But the real question is: Are students finding it useful?”