Who can I call about eviction, hunger, child care? Inside Hudson Valley's 211 helpline

The callers gave just a first name, or no name at all. For some, it was hard enough to place the call to ask for help — even though the number is just three digits long.

2-1-1.

Terry in Highland Falls watched floodwaters rise during July’s massive rainstorms and was worried about the safety of electric lines. He dialed 211.

Marta in Monsey wanted out of a domestic violence situation and had family on Long Island. She dialed. Adriana in Glen Cove was dealing with depression. She dialed.

Alvita is a home-health aide whose client, a female senior in Mount Vernon, was facing eviction. A church employee from Plattsburgh saw a family outside his church who had nowhere to stay. They spoke only Spanish. He dialed for them.

Whatever the reason for their call, and wherever they called from — whether from the tip of Long Island, across the Hudson Valley or in three Adirondack counties near the Canadian border — their calls connect to a non-descript 24-foot-by-24-foot room on Central Avenue in White Plains.

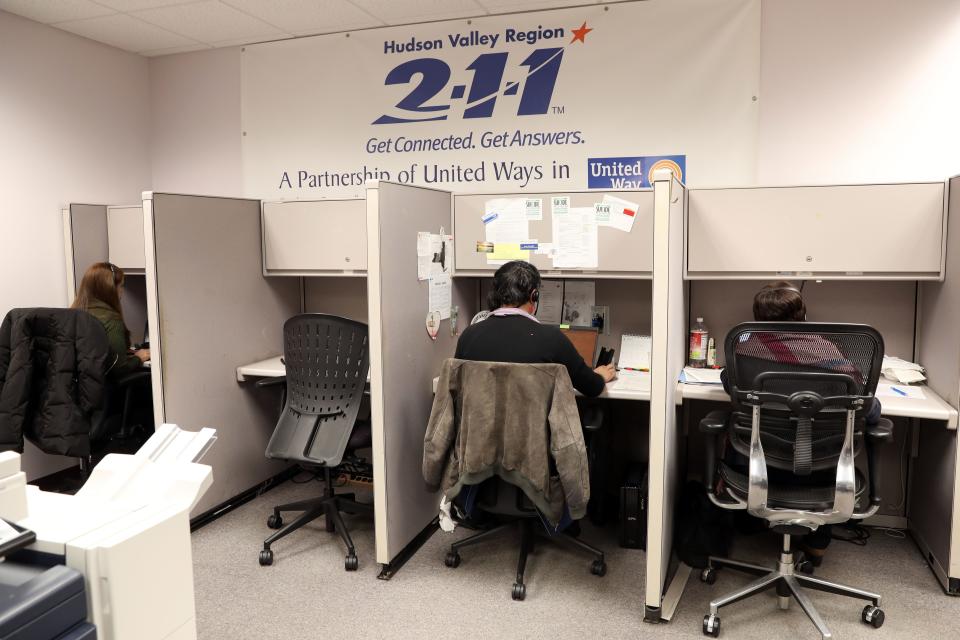

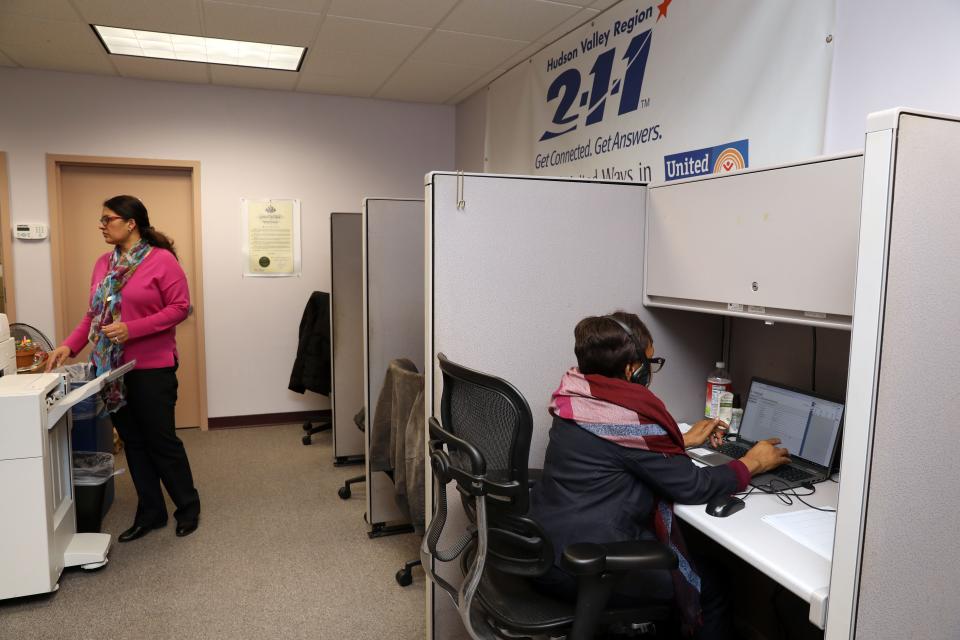

It's the United Way's Hudson Valley and Long Island regional 211 call center — and it's nothing fancy.

Eleven cubicles face the gray walls. A printer/copy machine dominates the middle of the room. Headsetted counselors field calls 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Some work from this office. Others work from home. A flat-screen monitor near the room’s only door shows manager Lini Jacob — chief information and referral officer at United Way of Westchester and Putnam — who is working and where.

Whether seated in a cubicle in this gray room in White Plains or at a laptop at home, counselors use the web-based portal to answer calls and access a far-reaching database to point callers in the right direction.

There are 12 counselors, and a few supervisors. In a major crisis — Hurricane Sandy, for example — volunteers are added to handle a crush of calls about shelters, where to find a shower, where food is being distributed.

The trained call specialist answers the phone with only their first name, and asks only for the ZIP code of the person calling, to provide specific location-based services.

The cost of a family in Lower Hudson How much does it cost a family to make it in Westchester, Rockland? You'll be surprised

One call, several referrals

Tom Gabriel, the president and CEO of United Way of Westchester and Putnam, said 211 is marking its 20th anniversary this year, with hotlines nationwide. Gabriel said the specialists know the right questions to ask.

“Someone’s calling up and saying, ‘I’m having trouble feeding my family. Can you tell me how I can get food?’ A trained call specialist knows to ask about everything that’s going on. ‘Have you lost a job recently?’ Then you dig a little and you find out this person is also facing an eviction, they need rental assistance, they need eviction prevention more than just the food pantry.”

One call can result in several referrals, to any of 25,000 programs in the Long Island, Hudson Valley and Adirondacks regions. Those programs update their offerings all the time, meaning that 211 has to update its database all the time. If a food pantry has several locations, but closes one for restocking, or changes its hours, the call center needs to know that.

The White Plains call center fields calls from Westchester, Rockland, Putnam, Orange, Dutchess, Ulster and Sullivan counties in the Hudson Valley, Nassau and Suffolk counties on Long Island and Essex, Clinton and Franklin counties in the Adirondacks. (A separate regional call center handles the Capital Region.)

Said Gabriel: "It's a grand total of about 6 million New Yorkers who, if they pick up the phone and dial 211, they're going to get us."

‘We offer hope to the hopeless’

Lini Jacob is soft-spoken, her presence warm. She’s the kind of voice you’d want on the end of the line if you were at the end of your rope. She reassures. So do her call specialists.

Call by call is met with a calm counselor on the other end of the line, a rare bit of human contact in a world too often turned over to touchtoned impersonality. The trained counselor’s first job is listen, to make a human connection. Then, by asking just the right questions, they tease out more details, facts that might suggest other services to help the caller.

Jacob puts it simply: “We offer hope to the hopeless.”

“There's a stigma in asking for help and it doesn't need to be there,” Jacob said. “With 211, there is that confidentiality piece. They don't know me. They are not seeing my face. So it's OK to call."

“Sometimes callers will reach the 211 line by saying ‘I'm looking for help for someone else,'" she continued. "But I will say that at the end of the call, sometimes they will say — if they connect with the staff during the conversation — ‘I want you to know that it was actually for me.’”

AVITA’S CALL: Seniors isolated by technology gap

Gabriel said seniors are reluctant to call, and isolated by a lack of technology. He shared the story of Alvita, a home-health-care aide, who called on behalf of her female senior client in Mount Vernon.

“She learned that her patient was given an eviction notice and was concerned about finding a new place to live but was also reluctant to reach out for help and did not have internet,” he said.

“Alvita asked about options for eviction prevention, as well as housing-search assistance focused on seniors, and promised to share them with her patient. As a result, we provided a number of referrals around legal services and supportive housing for seniors.”

Can religious groups sidestep zoning? NY bill would clear path for religious groups to build affordable homes on their land

A spike in referrals

From calls to one number — 211 — came hundreds of thousands of other numbers — referrals — which have skyrocketed in recent years.

In 2023, counselors on the 211 regional help line in the White Plains office provided 661,006 information and referrals.

In 2022, there were 580,420.

In 2021, there were 452,109.

In 2020, when the COVID pandemic hit, referrals spiked nearly 16%, to 523,919.

In 2019, information and referrals totaled 452,839.

TERRY’S CALL: A call about one emergency reveals another

Calls to 211 increase during natural disasters, when a crisis can reveal several looming problems.

Gabriel shared the story of Terry, who called from Highland Falls when July rainstorms caused massive flooding in Orange County.

“He asked how to have a building inspection performed to determine electrical safety,” Gabriel said.

“But after a short conversation, our 211 call specialist determined that Terry was a senior and lost important medications in the flooding. Besides giving him a referral to several housing-focused nonprofits, we also guided him to nonprofits providing medication expense assistance.”

Calls on the rise: Housing, food, child care, financial aid

The calls to 211's regional center have spiked in the past two years, in certain call areas. In 2023:

Housing insecurity calls were up 20%, on top of a 20% increase in 2022;

Food insecurity calls were up 40%, on top of an 80% increase in 2022;

Child care calls rose 30% on top of a 30% increase in 2022; and

Calls regarding financial assistance with rent or utilities were up 20%, after a 115% increase in 2022.

The spikes in 2023 followed staggering increases in 2022 came "when the rug got pulled out," Gabriel said, meaning when emergency rental assistance disappeared, when the child tax credit disappeared, when all of those stimulus measures disappeared.

MARTA’S CALL: Fleeing domestic violence, looking beyond her borders

Some calls are more desperate than others, and require a regional network that the call center can tap into during a crisis.

Gabriel shared the story of Marta, “a wife in Monsey (who) called seeking to escape a domestic violence situation.”

“Because she had family in Long Island, we connected her to a shelter program in that area. We made a follow-up call the next day to determine if additional assistance was needed and Marta told us she had spoken to the shelter on Long Island and that they were helping her.”

Connection, not algorithm

Jacob said the personal connection provides something Google can't.

"People wonder 'Why call 211 instead of googling information?' Of course, there is that human interaction. People calling the 211 line sometimes don't know how to express their needs. So imagine they're searching information. Google doesn't know how to talk them through what's going on. It's very limited."

Google, for example, can't hear the baby crying in the background and ask a mother, who is new to Putnam County, if she has applied for WIC or SNAP benefits.

A straightforward call might take five to eight minutes, Jacob said. Calls involving rent assistance or evictions could be 15 to 20 minutes. But crisis calls are open-ended and could last 40 minutes or longer, Jacob said, "because we are involving 911 in the mix."

A CALL FROM PLATTSBURGH: A family in need

Often, 211 is the first call someone makes when they need help, no matter what language they speak.

Gabriel shared the story of a church employee from Plattsburgh, in Clinton County, who called 211 to say there was a family outside his church, seeking shelter.

There was a language barrier — they only spoke Spanish, which the church employee didn’t speak. The call specialist spoke Spanish and learned that the family was from Argentina and had nowhere to stay and no family or friends to help.

Knowing that all homeless cases in Clinton County begin at the county’s Department of Social Services, the call specialist referred the family there.

Gabriel said that if a caller speaks Spanish, a staff member can take that call immediately. If they need help in another language, he said, “we connect to a third-party service immediately that can translate up to 200 different languages.”

'This job is not for everyone'

Spending a work day helping people who feel they have nowhere else to turn isn't easy, Jacob said.

"You may not know what others are going through," she said. "This is a reminder for me each day. 'Lini, stop complaining about what you don't have.' Because when you hear people asking for food, when you hear people say 'I don't have a place to stay...'"

At this point, Jacob loses her composure briefly, overcome by what she hears on a daily basis.

"You really need to be humble enough to help these individuals. You really need to have that part. This job is not for everyone," she said.

Most of the call center staff has been on the job for five or six years, Jacob said, who see the work as giving back to the community.

ADRIANA’S CALL: ‘A weight has been lifted’

Gabriel said one call for help can reveal a multitude of problems facing a family.

He shared the story of Adriana, a wife in Glen Cove, who called and said she had been suffering from depression for several months.

“After a brief back-and-forth conversation, our call specialist discovered Adriana and her family were food insecure,” Gabriel said. “Her husband had his work papers and was working as a landscaper, but in the winter he had no work, so the family was starving.”

The first referrals were to local food pantries, then to how to apply for SNAP benefits, then information about how to contact her utility company to sign-up for the low-income discount rate program, Gabriel said. She was also referred to the NAMI mental health warmline, a peer-run hotline that offers emotional support from volunteers who are in recovery themselves.

Said Gabriel: “At end of call she said, ‘I opened my heart to you and now I feel like a weight has been lifted.’”

Funding slackens

While the successes are real, the problem with 211, Gabriel said, is that its $1.2 million annual budget comes from government contracts and support, "and the main motivator on government is keeping costs to a minimum, and they almost never give cost of living increases."

"We have significant funding from Westchester County and they're incredibly generous and supportive of us. And we have smaller funding through Dutchess and Rockland and all the way up."

The $1.2 million budget covers 15 staff members with health care and 403(b)'s, but the pay isn't great — an entry-level minimum of $20 an hour — which is up from $16 when Gabriel started in 2019.

"We've made a significant investment in our staff. It's still not a good number," Gabriel said. "Frankly, we have to make it higher for these individuals, but we have we've only gotten a 2% raise from the county in probably ten years."

There are eight 211 call centers in New York, not all of which are served by the United Way. There is a bill in Congress to provide federal funding for 211, supported by the local delegation.

Unprecedented need

The pandemic brought unprecedented need, and unprecedented demand for 211, Jacob said.

These were people who had never asked for help in their lives. Their calls were tinged in anger.

"I remember a call from a man who had served in the military. He was so upset that he needed help. He kept saying: 'Why can't you help me out?'"

The 211 line also fielded call after uncertain call about where to get COVID tests, and then vaccines.

"We were that front line," she said. "People said: 'I've never asked for this kind of help in my life. I was making money but I got laid off. We were not ready for it.' It wasn't so much 'How can you help me?' as it was 'I need that help. You need to help me.'"

That kind of desperation has abated in most areas, but one: the crushing need for housing.

The housing needs have only increased, particularly with the loss of pandemic-era rent supports.

"In Westchester, subsidized or low-income housing is hard to find," Jacob said. "People are always looking for rent support. Regardless of the region, we do see an increase in housing cots, in people looking for rent help."

On the line: 'Thank you for listening'

The phone calls are mundane, even boring, but vital.

A woman called on behalf of a 76-year-old patient who needs to have meals delivered to her home in Mount Vernon. In less than five minutes, Josephine, the 211 call specialist, gave her four agencies that could help.

A woman from Mount Vernon called for help with her ConEdison bill. Call specialist Jessica learned that the woman wasn't facing a shutoff notice, that she had received help from the state's HEAP program to help New Yorkers heat or cool their homes, but that she needed more help. She gave the caller four phone numbers, closing the call by saying: "You're welcome. Be safe and take care."

A social worker from Yonkers called about a mother with two children who are in wheelchairs. "She's currently picking them up and bringing them in and out of the apartment," the caller explained, but hoping to find an apartment with a ramp or an elevator. Call specialist Charlie apologized for only being able to find two agencies that might provide help or advocacy. She closed the call with: "Thanks for calling 211. Call us anytime."

Call specialist Jessica answered another call, from a mother of two in Yonkers who heard about evictions in Dutchess County and was concerned. She wasn't facing eviction "just yet," and she was currently paying her rent, but she was eight months in arrears.

Jessica tracked what different agencies had told the caller, and helped her come up with three paths forward. She could petition social services for a "one-shot-deal" assistance to clear the arrears, explaining she wasn't looking for ongoing assistance. She could try to secure funding from other sources. Or she could work with her landlord on a plan to pay a little extra each month.

Before the call was over, the caller had four phone numbers to call, including for legal help — and a Plan A, B and C.

The caller sounded relieved to have a path forward.

"You have been a great help. Thank you so much," she said. "And thanks for listening." She closed the call with another "Thank you, Jessica" and a soft "God bless you."

Is making ends meet a struggle for you?

If you're having trouble getting by in Westchester, Rockland or Putnam counties, we'd like to hear from you.

How hard was it for you to find housing? Is your grocery bill unbelievable? How long did it take you to find child care you could afford? Share your story and you might be contacted for future stories about affordability — or unaffordability — in the northern suburbs.

Reach Peter D. Kramer at pkramer@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Rockland/Westchester Journal News: Hudson Valley's 211 helpline: Inside a front line on hunger, eviction