ByGone Muncie: The Granville Whitecap's night of terror in 1895

About 11 p.m. Monday, Feb. 25, 1895, four masked men burst through Amanda Hamilton’s front door at her house in the village of Granville, about nine miles northeast of Muncie. According to the Muncie Daily Times, the assailants seized Amanda then hogtied and gagged her. She was pulled outside and ruthlessly whipped “in a fiendish and brutal manner.”

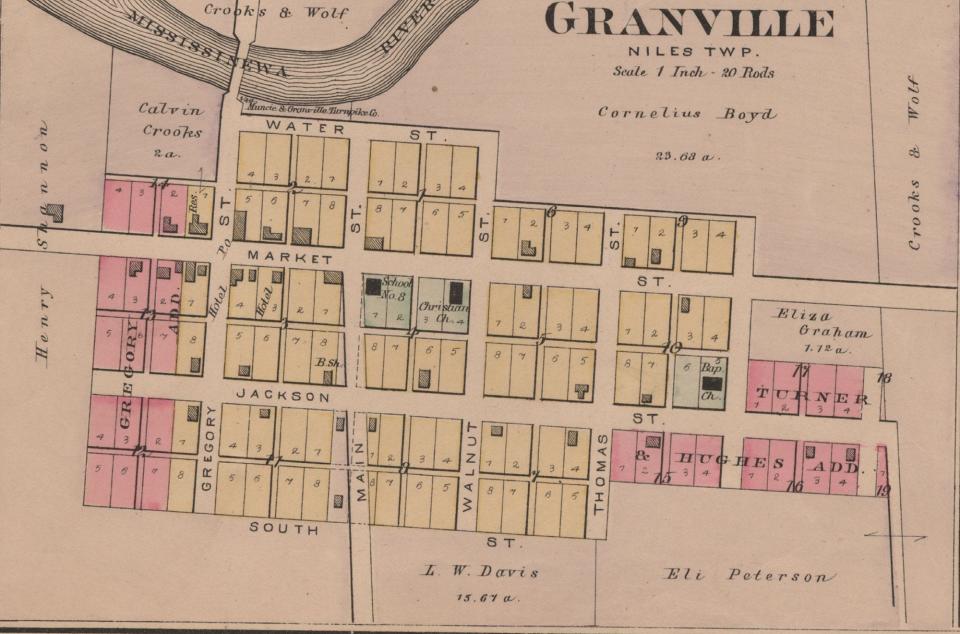

In the commotion, Amanda’s 9-year-old daughter Lillie ran to her grandmother Eliza Graham’s house next door, “to tell Grannie that her mother was being killed.”

Eliza, who was 72 at the time, ran out to save her daughter from the goons. She later testified that the men wore white “paper flour sacks on their heads,” with slits cut to see and breathe.

One of the men yelled through gin-soaked breath, “give the old woman a few licks and that will settle her.”

Grannie Eliza shot back, “Whip me if you want, as you cannot cheat me out of many days.”

Apparently unable to challenge the logic, they stopped and Eliza dragged her daughter Amanda back inside.

The hooded attackers then entered Eliza’s home and found a sick Charles Hamilton suffering in bed. Charles was Amanda’s ex-brother-in-law and was boarding with Eliza. The men forced him outside where he too was “unmercifully flogged” with buggy whips.

The Morning News also reported that Amanda’s two young teenage sons Warren and Clay were assaulted, along with a neighbor named Lewis Beech, who tried to intervene.

After the beatings, the hitmen ransacked both homes, smashing dishes and breaking apart furniture. When they found a bloody Charles Hamilton hiding in Amanda’s kitchen, they held him “over a cook stove, burning the flesh on his hands and arms.”

Before exiting, they warned Amanda to leave the village with her family or else suffer worse violence.

Two days later, Amanda Hamilton made her way to Muncie and reported the attack to police. At the time, the Muncie Police Department ran a metropolitan jurisdiction that covered Delaware County.

Amanda told police she had lived in Granville for almost 20 years. As such, she recognized each assailant and identified them as Arthur Sherry, Elmer Bales, Rolly Wright, and Niles Township’s justice of the peace, Walter Berry.

MPD patrolmen Noble Thornburg and Lew Coffey rode out to Granville to arrest the villains on charges of assault and battery, public intoxication and trespass. The prosecutor later refiled charges accusing them of “riotous conspiracy.” All four pled not guilty and were released on bond.

Local papers identified Sherry, Bales, Wright and Berry as whitecaps, a kind of vigilante group organized to force "moral" standards and traditional (white male) rights through extrajudicial violence. Whitecaps employed many tactics, including warning letters, floggings, beatings, arson and lynching. Today we’d call them domestic terrorists.

The movement flourished throughout the United States after the Civil War. Whitecaps targeted anyone deemed immoral, especially women, immigrants, and African Americans who crossed white-drawn color lines. Assailants left threatening notices with a bundle of switches and then attacked at night in masks.

Whitecaps used comparable dress and tactics as the first Ku Klux Klan, but were separate groups with different objectives.

Whitecapping was popular in Indiana. One source indicated that it actually began in the Hoosier state sometime in the mid-19th century. The most famous Indiana whitecap incident was the lynching of the Reno Gang in 1868. Sixty-five whitecaps sacked New Albany’s jail on Dec. 11 and hung the marauders from a stairwell.

In 1892, Muncie madam Kate Phinney received a whitecap notice, threatening violence if she didn’t close her southside brothel and leave town. Neighbors grew tired of Phinney “operating her dens of iniquity,” according to the Daily Herald, and rose “in arms against her and contemplated taking the law into their own hands.”

Phinney paid the warning no nevermind and told a reporter that she had “one shotgun in readiness” with two more on the way to arm the prostitutes in her employ. They would “resist the white caps” with any means necessary.

In 1897, whitecappers using the name “Delaware County Gang” were employed to terrorize an eastern Madison County farmer named Fred Bronnenberg. Fred had “gained the ill-will of the neighborhood” when he opposed a new road slated to go through his property. Whitecaps set his fence on fire and left a notice to “keep your horses out of the barn if the road is not opened.” The letter, written in red ink, closed: “this is a warning for you. Delaware County Gang. Sign of fire.”

One morning in mid-October of 1898, Arnold Zeph, a bartender at Henry Foreman’s southside saloon, went to open the joint and discovered a whitecap notice at the front door. Foreman had recently hired an African American porter named Cicero Nelson. The poorly written letter warned Foreman to fire Nelson because, “we don’t want no negrows in Shedtown.” The Daily Times reported that the letter was the “culmination of an effort to get rid of Nelson, begun several weeks ago.” Whitecaps torched the saloon four days later.

The 1895 assault in Granville was the only reported brutally violent whitecap attack I could find in Delaware County’s history, but whitecaps remained active in the area until at least 1907.

Amanda Hamilton was a whitecap target likely because she was divorced. Local rumors also spread because her ex-husband’s brother was boarding across the way with her mother, Eliza. The News wrote that both women “lived quietly, interfering with no one but from time to time, rumors were circulated by meddlesome neighbors that they were conducting a bawdy house.” This wasn’t true, but even if it was, the violence wasn’t justified.

At the first hearing, the defendants’ lawyers argued for a change of venue to evaluate testimony and evidence. A second hearing was held at a schoolhouse in Royerton by Hamilton Township’s justice of the peace, George Mansfield. Amanda and her family testified along with neighbors, all of whom “made a very strong case against the accused.” But prosecutors didn’t have enough physical evidence, apparently, and the case passed to a Delaware County grand jury. According to the Morning News, “there was much more beneath the surface that had never been brought out.”

After that, the story disappears from the record.

I can’t find a follow up in any surviving local newspaper and court records go cold. Like so much violence against women in American history, the whitecap attack in Granville was swept under a rug of social convenience and forgotten.

Chris Flook is a Delaware County Historical Society board member and a senior lecturer of media at Ball State University.

This article originally appeared on Lafayette Journal & Courier: Reign of homegrown terrorists known as Whitecaps ended in 1895