Burnet bound: A spooky jail, a Texas fort and vanished Mormon mills await in this county seat

BURNET, Texas — The second stop during a July day trip to Burnet County was this handsome county seat that, on the face of it, has taken full advantage of the numerous fine stone quarries in the region.

Before that, I had visited Marble Falls, the largest town in the county, where I was drawn to a local history museum in an 1891 school building; the story of a pioneering woman mayor; an old-fashioned diner that serves famous pies and has been around for more than 90 years; a legacy flock of faithful, more than 120 years old, that plans a Black history museum; and a small cave with a murderous past.

Burnet, during my short stay, appeared a bit less oriented to the tourist trade than Marble Falls, perhaps because it does not sit right above a lake. Its historic downtown nevertheless looks spiffy and welcoming.

Like most Texas county seats, Burnet sits in the middle of the county. And its granite-faced, art-deco courthouse, along with allied agencies and businesses, is right in the middle of the town.

The original settlement came together in the late 1840s when a federal military fort was established in the Hamilton Creek Valley — which had served as part of a prominent Native American trail — to discourage Comanche raids. At first, the settlement was called Hamilton, or Hamilton Valley, after landowner John Hamilton, also namesake for the creek.

More:A short but intense visit to historical Burnet, Texas

In 1858, the village of 35 residents petitioned to change the name — another Hamilton already existed about 70 miles to the north. It became a wool distribution center when, in 1882, the Austin and Northwestern Railway reached Burnet via Bertram. Originally a narrow-gauge line because of the tight curves in the rugged Hill Country, it was converted to standard gauge in 1891.

Burnet remained a market town during the 20th century in part because it sits at the intersection of two main highways, U.S. 281 and Texas 29. Area parks, lakes, caverns and hunting leases have helped augment the town's economy and culture as it moved into the 21st century. The pandemic only increased the popularity of Hill Country cabins as remote getaways.

So says Blair Manning, the whip-sharp tourism and marketing director for Burnet County. Manning not only oversees short-term leases in the county's unincorporated areas; she has raised the visibility of regional tourist magnets from her roll-top desk at the newly renovated Burnet County Old Jail, which was reborn as a visitors center in April with a ceremonial "chain cutting."

Burnet County Old Jail worth a short visit

Quite a few Texas counties have preserved decommissioned county jails, usually not far from their courthouses. Some were designed to look like medieval dungeons. History buffs have turned a few of them into museums.

Yet few are as curiously authentic as the 1884 Burnet County Old Jail, decommissioned in 1982 and reopened earlier this year.

County Judge James Oakley took on the jail rebirth as a personal project. When I visited, he happened to be meeting with constituents there, and he told me about the careful building process, executed by county maintenance staff, that preserved, for instance, prisoner scratchings on the walls, as well as enlargements that make it an inviting, if a bit spooky events venue.

On the first floor, find a woven metal "drunk tank," manufactured in St. Louis, which held perpetrators of minor offenses, along with artifacts from the building's active years as a lockup, including a sign that announces visiting hours between 2 p.m. and 4 p.m., plus the warning: "Do Not Talk to Prisoners Through the Bars."

Oakley recalls that, during his childhood, his mother habitually walked him close to the jail on their way to the nearby Baptist church. Through the bars, prisoners beseeched favors from the passersby. Oakley assumed that his mother meant the route as a moral admonition for his future.

Texas history, delivered to your inbox

Click to sign up for Think, Texas, a newsletter delivered every Tuesday

Robert Brewer serves as tour guide at the jail. In costume, he playfully stood guard over the "drunk tank," where repeat offenders often let themselves in, slept off their stupors and then stayed for breakfast. A sheriff's log displayed nearby reveals that public intoxication and DWI were the most common crimes.

A memorial statue of Sheriff Wallace W. Riddell stands in front of the jail. Riddell, born in 1899, served as Burnet County Sheriff from 1939 to 1978. At that time of his death, he was the longest serving sheriff in Texas. His family lived in comfortable quarters inside the jailhouse. The family's two bedrooms are now outfitted with appropriate vintage furniture and décor.

A living source of historical background during the jail revival project was Vonnie Riddell Fox, 95, daughter of the long-tenured sheriff.

"She remembers how it was all set up," Brewer says. "The children slept in four beds in each corner of this room; the parents in the other."

One can only imagine what went on in the solitary confinement cells dedicated to more serious criminals, which stand at a good distance from a small women's cell and other ancillary rooms.

Fort Croghan's short days on the frontier

I didn't know what to expect to find at Fort Croghan, located on the south side of Texas 29 about one half mile west of U.S. 281. I missed the entrance twice.

As one enters the grounds, a utilitarian building to the right houses a museum run by the Burnet County Heritage Society. Deeper into the grounds, stone and wooden structures stand ceremoniously around a rectilinear open space.

Two of those buildings above Hamilton Creek date from the fort's short time as a frontier outpost, 1849 to 1853, part of the federal military's initial string of barrier forts that included Worth, Graham, Gates, Lincoln, Inge, McIntosh, Duncan and Camp San Elizario.

One of those oak-and-stone buildings served as a lookout on the west side of Post Mountain, which rises to the south of the fort. It was later transported to current site. The role of the other early fort structure, also small, was unclear to me.

More:The historical miracles of Marble Falls, Texas

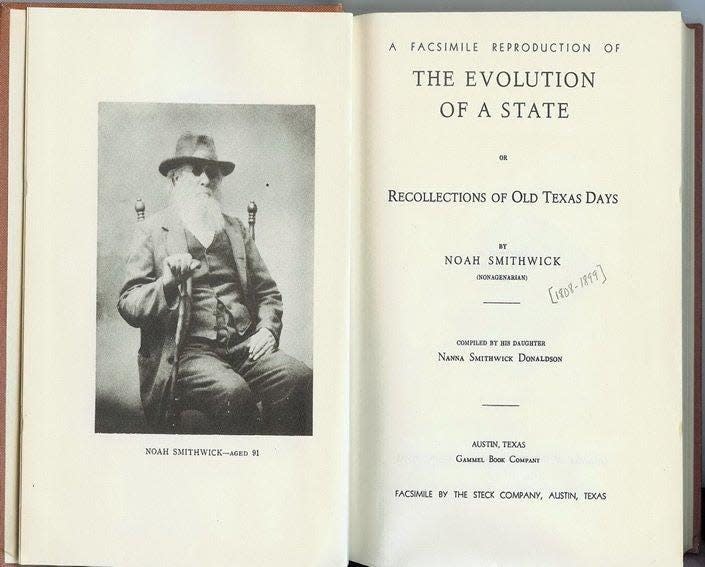

In his entertaining and trustworthy memoir, "The Evolution of a State: Recollections of Old Texas Days," Noah Smithwick, the fort's armorer, remembered that Henry McCulloch had maintained a camp of rangers near this spot, and that the fort "consisted of the usual log cabins, enclosed by a stout stockade, and was manned by one company of cavalry and one of infantry."

The fort was named in honor of Col. George Croghan and was previously located three miles down the creek. It became the headquarters for the Second Dragoons in 1853, but only few straggling guards remained until 1855 when it was abandoned.

Currently collected and neatly laid out on the grounds are a country schoolhouse, farm structures, store rooms and tools, all transported from around the county.

The best outfitted stone cabin was built by Logan Vandeveer (1815-1855) for his daughter on Hamilton Creek. Vandeveer was wounded at the Battle of San Jacinto during the Texas Revolution. He sold beef to federal troops at Fort Croghan.

By 1853, the frontier had moved west and some federal forces headed to Fort Mason, others to San Antonio. What remained of Fort Croghan was used intermittently for defense by Burnet settlers, but also as residences. By 1940, according to the Handbook of Texas Online, all that remained were foundations.

So little of the original material remains, it's hard to get a sense of what went on here. Still, it's worth a stop.

That utilitarian building up front, also operated by the heritage society, is packed with fascinating artifacts from the county's past, which two volunteers gamely explained.

Bursts of published Burnet County history

As J. Frank Dobie once wrote: Smithwick's "The Evolution of a State" is the "best of all books dealing with life in early Texas."

A blacksmith by trade, Smithwick was an inventor, frontiersman and astute businessman who wrote about his times at San Felipe de Washington and Fort Coleman, near Austin, and beyond. He's a terrific storyteller, a fair judge of character with a fairly open mind.

I had forgotten how much of Smithwick's amusing book is devoted to the earliest days of Burnet.

"As was the case in every settlement, as soon as practicable, a school was instituted, the promoters of the enterprise in Burnet securing the services of one W.H. Dixon, graduate of Oxford University, as teacher," Smithwick writes. "Under the efficient guidance of Professor Dixon, the school attained high rank among the educational institutions of the western country and became an important factor in the growth of the town.

"There, in a little one-room log house, the young idea was taught to shoot straight toward Oxford, Greek, Latin and the higher mathematics sitting in the same room with the little tot with his pictured primer. As in most schools of that day, elocution was assigned a high place, and embryo Websters and Adamses and Bentons harangued the school and its visitors at frequent intervals."

More:What history tells us about devastating Texas droughts

Smithwick wrote about the petty corruption, minor feuds and dashed ambitions at Fort Croghan. He hunted bears, rounded up wild cattle and entertained visitors from the rest of Texas in his modest digs. He got to know fellow inventor Gail Borden (1801–1874) of condensed milk fame, and Captain Jesse Burnam (1792–1883), active during the Texas Revolution, who had retired to Burnet County near Double Horn.

Smithwick describes weddings, rousing camp meetings and roving orators. He grew particularly close to a group of breakaway polygamist Mormons whose previous mills had been washed out near Austin (Mormon Springs below Mount Bonnell) and Fredericksburg (Zodiac on the Pedernales River). They had set up a mill on Hamilton Creek south of Burnet, which came with its own flooding problems.

Smithwick delighted in finding ways to improve the mill and he eventually purchased it from the Mormons. He opened a store in what was called Morman Mill Colony, then later moved to the Double Horn settlement a few miles down the Colorado River from Marble Falls, before leaving for California at the start of the Civil War.

In advance of my day trip, I enjoyed a short book, "Front Page News from Burnet, 1929-1939" by John Hallowell. Hallowell's is a year-by-year account of news stories that appeared in the Burnet Bulletin during that decade.

While the local fallout from the 1930s drought and the Great Depression are ever present in this book, the Bulletin newspaper cheered the arrival of the big highways, the labor by the Civilian Conservation Corps on Longhorn Caverns, and the back-breaking work on Buchanan Dam, which, to my surprise, was started by a private utility company, then abandoned in the mid-1930s. Congressman James "Buck" Buchanan, chairman of the House Committee on Appropriations from 1933 to 1937, came up with the federal money to rescue the project, which was taken over by the Lower Colorado River Authority.

Lyndon Baines Johnson succeeded Buchanan as U.S. representative and he helped shepherd the larger Highland Lakes project to its completion.

In addition to these two books, I'm fond of the slim volumes of community history put out by Arcadia Press. If you are familiar with this valuable series, they are laid out on similar templates and focus on historical images accompanied by chunks of local history.

Two for your Texas history collection regarding Burnet County: "Marble Falls" by Jane Knapik and Amanda Rose, and "Burnet" by Carole A. Goble. Although it take less than an hour to read each of the books in this history series, they turn into invaluable reference works.

Michael Barnes writes about the people, places, culture and history of Austin and Texas. He can be reached at mbarnes@statesman.com.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Burnet: A spooky jail, rekindled Texas fort and vanished Mormon mills