'Buddy sap' is no friend to maple syrup producers. Now local researchers have a test for it

A new test developed by researchers at Carleton University to detect low-quality sap is being hailed as a solution to prevent thousands of litres of maple syrup from going down the drain every spring.

Bad sap is referred to as "buddy sap," and it's almost impossible to detect before it's turned into syrup, said Brian Barkley, the owner of Barkleyvale Farms in Chesterville, Ont.

"You can't taste it, you can't smell it, you can't see it. It only appears after you've done all the work of boiling it all down," said Barkley, who's run the farm since 1974.

The resulting syrup tastes like a "burnt Tootsie Roll," he said.

That inability to predict when sap goes bad means producers must often halt their work well before the end of the season, Barkley said.

"They're potentially not producing syrup that they could be out of fear that [they'll] go to all the work of putting all the sap into the machinery, boiling it all down and everything — and then it's not going to be usable," Barkley said.

"That's a lot of work and a lot of wasted expense."

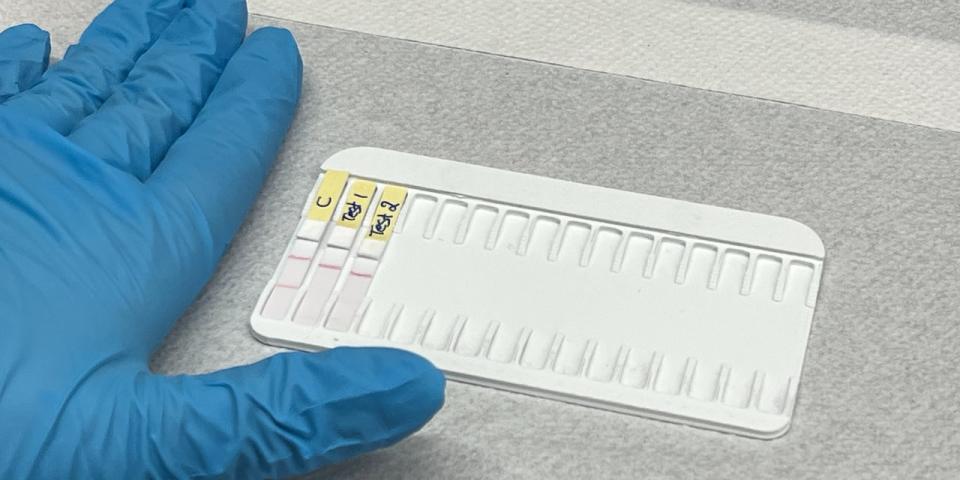

The sap tests resemble COVID or pregnancy tests. Two lines indicates that the sap is still good, while one line indicates it's gone bad. (Giacomo Panico/CBC)

How the test works

Developed by the Laboratory for Aptamer Discovery and Development of Emerging Research (LADDER) at Carleton, the test involves using a strip similar to a COVID or pregnancy test.

The strip is placed in the sap sample and left for two minutes, after which one or two lines will appear. Two lines indicate the sample is clean. One indicates it's buddy and can't be turned into maple syrup.

The research team worked closely with local producers to develop the test, said Erin McConnell, a research scientist involved in the project.

"We can say to people like Brian, we can build this tool for you. We can work with you from the very beginning of the project. We're working with maple syrup producers to really find out what's practical," she said.

Brian Barkley, right, visits the Carleton University lab to see how sap samples are tested, while researcher Erin McConnell, left, looks on. (Giacomo Panico/CBC)

Old tricks not as helpful

Maple syrup producers often rely on "farmers' tricks" or "old wives' tales" — like watching for pussywillows or listening for frogs in the swamp — to determine if sap is still usable or not, Barkley said.

Those old tricks were "surprisingly pretty good," he said, but have proved less reliable this year.

"The weather patterns have just been so screwy, it's so unstable. So all of a sudden, a lot of the old signals were quite variable," Barkley said.

The LADDER team has conducted studies in the field with several producers in the Ottawa Valley and southern Ontario. They're hoping to expand their study to reach more producers across the province.

McConnell said so far, the results have been promising and the team is preparing to have the tests ready to go by next summer.

"Next year we hope to roll out the test kit to those same producers, and bring new ones into the trial," she said.

For research team member Shahad Abdulmawjood, a PhD candidate in chemistry who fell in love with maple syrup when she arrived from Iraq about a decade ago, the success is twice as sweet.

"Now I'm an official Canadian," she said. "It makes me so happy that I was able to help."