Bud Anderson, America’s last World War II ‘triple ace,’ dies at 102

Brig. Gen. Clarence “Bud” Anderson, the last American fighter pilot known as a “triple ace” for downing 16 German planes during World War II, died in his sleep May 17 at his home in Auburn, California. He was 102.

Born in Oakland, California, on Jan. 13, 1922, Clarence Emil Anderson Jr. joined the U.S. Army Air Forces on Jan. 19, 1942 and earned his pilot’s wings at Luke Field, Arizona, later that year. He entered World War II as part of the 357th Fighter Group, the first unit in the U.S. Eighth Air Force to enter combat equipped with the North American P-51 Mustang.

Over the course of the war, the Mustang was credited with downing nearly 600 enemy planes — including a record 17 of Nazi Germany’s Messerschmitt Me-262 jets — and destroying more than 100 aircraft on the ground. It also produced a record 42 aces, including Anderson, who at the end of the war had 16.25 victories to his credit. (Pilots are awarded a fraction of a “kill” if multiple airmen contributed to a plane’s downfall.)

That dogfighting earned him the moniker of “triple ace,” the military name for the rare pilot who has downed at least 15 aircraft in combat. Some others who achieved the same include Brig. Gen. Robin Olds, who shot down 17 aircraft during World War II and the Vietnam War; Capt. Joe Foss, who destroyed 26 aircraft in WWII; and Maj. Richard Bong, who totaled 40 aircraft kills in WWII.

Anderson then helped shepherd the U.S. military into the jet age as a test pilot at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio, and as a top test official at the Air Force Flight Test Center at Edwards AFB, California.

“He flew many models of the early jet fighters and was involved in two very unusual flight test programs,” Anderson’s website says. “He made the first flights on a bizarre experimental program to couple jet fighters to the wingtips of a large bomber aircraft for range extension. Later he also conducted the initial development flights on the F-84 Parasite fighter modified to be launched and retrieved from the very large B-36 bomber.”

He later commanded an F-86 squadron during the Korean War; oversaw an F-105 wing in Japan and flew Republic F-105D fighter-bombers over Vietnam as commander of the 355th Tactical Fighter Wing.

Anderson flew more than 130 different types of aircraft and logged more than 7,500 flying hours in 30 years of continuous military service, according to his website.

By the time he retired in 1972, then-Col. Anderson had accumulated five Distinguished Flying Crosses, 16 Air Medals, two Legions of Merit, a Bronze Star and a Commendation Medal. In 2022, the Air Force promoted him to the honorary rank of brigadier general.

Anderson married Eleanor Cosby in 1945 and raised two children. Eleanor died in 2015.

“We were blessed to have him as our father,” his children, Jim Anderson and Kitty Burlington, said in a statement on the pilot’s website. “Dad lived an amazing life and was loved by many.”

Anderson flew his first combat sortie on Feb. 5, 1944, and returned content that at least he had not “screwed up” and had gained invaluable experience and confidence in the process.

Anderson looked back on his breakthrough first aerial victory in a 2022 interview with Military Times.

“On March 8 we were heading home, three or four guys, with [1st Lt. John England] along with us. We saw a Boeing B-17 below us, smoking, so we were headed over there when three Messerschmitt Me-109s came up. … They didn’t even see us,” he said. “We cut them off at the pass and I saw one and said, ‘This one’s mine.’ I wanted one bad.”

The aircraft first engaged in concentric circles, he said: “It’s hard to get a shot in at 90 degrees.”

“I was pulling a lot of Gs,” Anderson said. ”I fired blind, and when he next came in view, black smoke was coming out — I got him in the coolant system. He went up and bailed out.”

But he soon questioned whether he had made the “luckiest shot in the world” — or if England, flying nearby, had gotten the kill instead.

Later at the officer’s club, once Anderson had convinced himself he wasn’t the victor, England ran over.

”'Best shooting I’ve ever seen in my life!’” Anderson recalled his wingman saying. “‘You hit that son of a bitch out there at over 40 degrees!’”

“The moment he turned, I ran — literally — to get on the telephone and claim my first victory,” Anderson said.

All of Anderson’s aircraft, P-51Bs and Ds, bore the moniker “Old Crow,” after the whiskey. Anderson’s last successes were two destroyed Focke-Wulf Fw-190s, and one probable kill.

“That was my first mission over Berlin,” he said. “I don’t think it was sensational. The quality of the Germans went down by then. One Fw-190 dived under the clouds; I just slid down and blew it up.”

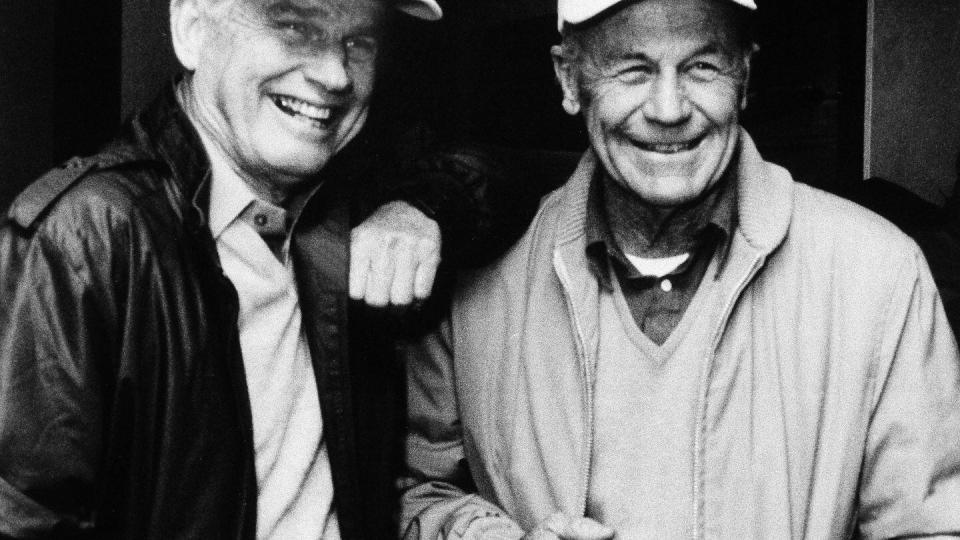

While assigned to the 357th Fighter Group, Anderson sparked a lifelong friendship with another fighter ace: Capt. Charles “Chuck” Yeager, the pioneering test pilot who became the first person to fly faster than the speed of sound.

In January 1945, the two set off over the Alps on a “sightseeing tour” for their last mission, Anderson recounted.

But as Anderson and Yeager were dropping their auxiliary fuel tanks on Mont Blanc and trying to set them on fire for fun, their wingmen elsewhere had more pressing matters at hand.

“When I learned that while we were joyriding over the Alps, the rest of the 357th had scored a one-day record of 56.5 shootdowns,” Anderson said. “I got sick!”

By then, Anderson had definitively made up his mind about the plane he flew.

“The P-51 was a great airplane,” he said. “I think it saved the world.”