Brutal witchcraft: What it really feels like to drive an F1 car

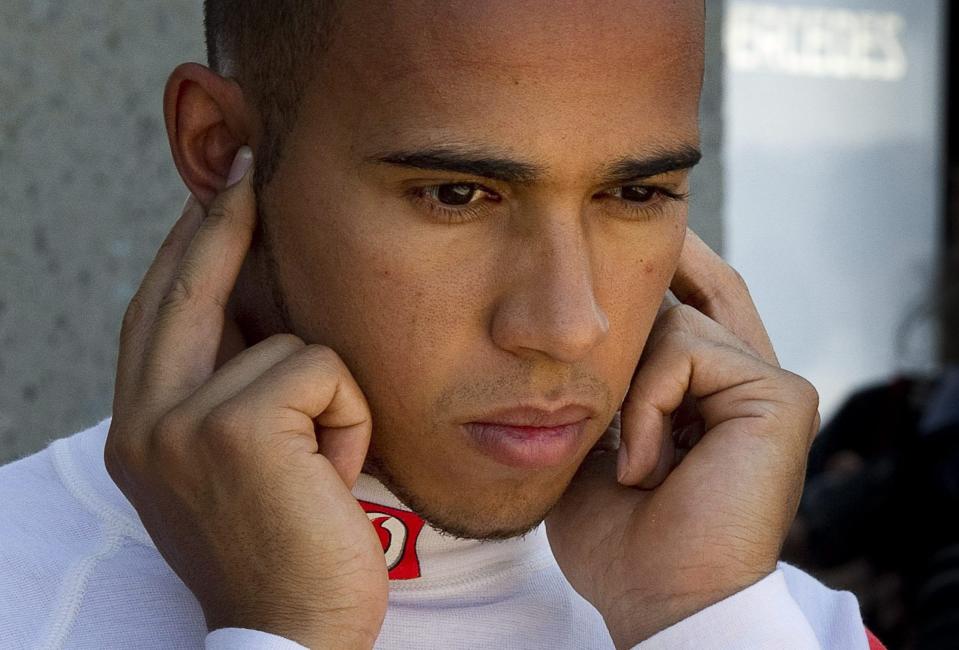

Lewis Hamilton is zeroing in on yet another Formula 1 championship and, despite having an up-and-down season, he has regularly made the challenge of driving an F1 car look like … well, look like no challenge at all.

So how much of an assault on the senses do F1 stars endure in one of these machines?

I spoke with someone who should know – David Coulthard, whose F1 career spanned 247 races and included 13 wins.

If Coulthard is right, then there could be more than a little wizardry (or witchcraft) at work …

Vision: The view’s not great but at least you can see the telly

Sitting in an F1 car is a bit like sitting on a beanbag, albeit one made of carbon fibre, with your feet on a stool… and doing 200mph.

Your bum is practically on the ground, and your head is less than half as far from the road as it would be in a family saloon. It’s not a great vantage point.

As if the helmet and head-and-neck restraint system weren’t enough to further restrict a driver’s vision, F1 cockpits also have high sides, to protect those racing stars when things go wrong.

But it’s amazing what F1 drivers can see, even when travelling at north of 200mph.

Coulthard said: ‘You’re very aware of everything. If a photographer was to move at a corner, and you knew the guy, you’d recognise him and you’d mention it to him afterwards, which always kind of freaks them out.

‘If a marshall isn’t looking at you but is looking around the corner, that probably indicates that there’s been an incident. There might be a flag coming out.’

Then there’s the importance of knowing what’s going on behind you. F1 mirrors may not look terribly impressive, and they do vibrate a lot, but they have their uses over-and-above helping make the car behind stay behind.

Coulthard said: ‘They’re very important because they give you your only reference as to what’s going on behind you.

‘I used to have them set so I could look at the rear tyres, to gauge wear, blistering, things like that.

‘It’s not what you’d consider fantastic visibility but everything counts – a little peep through a keyhole is enough for a pervert…’

And then there are the huge screens dotted around tracks.

Drivers find it easy to see the trackside screens, even at a twisty circuit such as Monaco,

Coulthard added: ‘Monaco’s a great place – when you come out of Sainte Devote and head up the hill there’s a time the car comes to the right then it moves to the left then you move it to the right, then you’re braking into Casino Square.

‘You have such a feeling of timing and what’s required that you can look up at the big screen and you can see if guys are pitting, for example.

‘In the race car you’ve only got the vision of what’s going on from your visor. The team will pass a lot of information to you but, if it’s happening live on the big screen, you’ll know before the team have time to get their finger on the button and tell you Hamilton’s just pitted. You use every tool at your disposal.’

Sound: Loud, but not turned up to 11

Coulthard raced when F1 still had screaming V8 and V10 engines, that could hit 19,000rpm and would damage a fan’s hearing if they forgot to put earplugs in.

Nowadays, things are much more well-mannered, though hardly soporific.

‘You hear everything but the engine’s behind you, so the noise is being pushed out the back – it’s a quieter version of what you experience outside the car,’ said Coulthard.

And do drivers struggle to hear team radio transmissions?

‘A lot of the time I can’t understand what teams are saying on broadcast but I could understand them when I was in the car,’ he added.

‘It’s like listening to pilot communications in an aircraft – if you sit in the co-pilot’s seat but you’re not in the moment, you’re not dialled in, you don’t understand.’

It’s an F1 cliché that a crowd’s roars can be worth half a second a lap.

But hold that cliché – Coulthard admits it’s ‘not very often’ you actually hear the roars.

‘I did hear it once when I overtook Jean Alesi, under braking, down at Stowe Corner. I took the lead and I could hear the Silverstone crowd cheering, because my engine was on over-run, I was braking and there wasn’t much mechanical noise.

‘Even a V10 is only noisy when you push the loud pedal. An engine on idle or over-run is, relatively speaking, quite quiet.

‘It’s like when a rock band does an acoustic song – it’s still loud but, relative to the ear-splitter they were playing before, it’s not loud.’

Smell: Would you like oil or rubber with that?

It might seem like being cocooned inside a helmet, with air whizzing past at high speed, would mean there was little to sniff at in F1.

But the hot gasses coming off the cars have an aroma of their own, a mixture of oil, unburned fuel, brake dust and tyre smoke, depending on how the car’s being driven.

Coulthard, who is now a TV pundit and ambassador for beer giant Heineken, said: ‘You smell the track. You smell oil. You smell the tyres. You smell the hot fumes.

‘You smell the difference when you’re in the open air of the start-finish straight at Monza versus going through the forest at the back of the track.

‘The air is the same air that the public’s breathing. The way that you can smell what type of trees are around you when you’re walking through a forest is the same for us.’

Taste: Well, that depends…

Drivers do get to taste something less unpleasant than burning rubber. They all have an electrically-powered fluid bottle containing their favourite rehydrating drink.

But Coulthard usually opted to drive without the benefit of even additional water, never mind exotic electrolyte drinks or the alcohol-free Heineken ‘0.0’ which he is now an ambassador for.

Coulthard said: ‘I never used to carry the drink systematically because of the weight.’

A litre of water weighs 1kg and, as Coulthard says, weight is performance in F1, and so at hot races he would keep his mouth lubricated with chewing gum rather than water.

‘Carrying 10kg equates to about three-and-a-half to four tenths of a second extra per lap.

‘So carrying the water on board takes away performance, especially if you’re tall like me, because tall people already weigh more.

‘If you can’t train to be capable of doing a two-hour grand prix [without the water] then there’s something not right about your preparation.’

Having said that, at particularly gruelling races, such as the (now defunct) Malaysian Grand Prix, driving without additional fluids can bring its own penalty.

Coulthard said: ‘I did end up on a drip a couple of times, and I did end up feeling ill after some very hot and humid races, but that’s part of driving in F1. I suppose the guy who wins a boxing match has a bit of a sore head the next day…’

In terms of race preparation, the days of a James Hunt turning up dehydrated and hung over before qualifying are long gone. Indeed, Coulthard and Heineken spend a lot of time getting the ‘When you drive, never drink’ message out.

He said: ‘You couldn’t do it now. It was his (Hunt’s) time. They were having their last night out potentially.

‘It was a very dangerous sport and they were the modern-day gladiators going into battle, with not a high level of certainty that they were going to come back without an injury. Today you’d be very surprised if you were to come back with an injury.

‘When I was driving, I never felt in danger but I was conscious of the fact it was potentially dangerous. I’m not a risk taker – I wouldn’t have done it if I felt the odds weren’t stacked in my favour because it’s not the way I’m wired.

‘F1 is not a game of chance – it’s a science project which brings high-level engineering and precision manufacturing and quality mechanics together, and puts it in the hands of an individual who can feel the car as an extension of their body, who can take it to its physical limit and exploit its performance.’

Touch: As delicate as an F1 sledgehammer

Modern-spec F1 cars regularly subject drivers to forces up to 6g – that means their body feels six times heavier than it is as they corner at 150mph or brake from 200mph to 50mph within a few tens of metres.

Coulthard said: ‘When you brake it feels like someone hitting you in the back of the head with a sledgehammer, because it’s a very violent force that comes on with a spike.

‘You hit the brake pedal with a force of 120kg, which is a huge amount of effort, but part of that force is generated by the deceleration and you leaning on the pedal.’

In-car footage shows drivers ‘submarining’ down into their cockpits under heavy braking, despite being strapped in incredibly tightly by their harness systems.

There’s not much in the way of shock absorption in an F1 car, compared with a road-going vehicle. In fact, half of the suspension comes from those fat tyres.

So drivers do get a thump when they hit kerbs.

Coulthard said: ‘You feel it in the car, though the tracks have been largely sanitised. If you go back 30 years, kerbs were something that would split the car in two.

‘Yes, they attack your senses when you go over the rumble strips but, as long as it’s not damaging the car, then, if it’s giving you the opportunity to go faster, then you will do it.

‘A racing driver would learn the Japanese national anthem backwards while juggling chainsaws if it would give two-tenths of a second off lap times.’

What is truly amazing is just how much punishment these cars can take in a crash while protecting the driver.

When Robert Kubica crashed at the 2007 Canadian Grand Prix, he went almost headfirst into a concrete barrier at 186mph.

Sensors indicated he had decelerated with a force of 75g – at the moment of impact, Kubica was being squeezed against his restraints with a force of five tonnes. He got away with a sore ankle.

So, what’s it really feel like? Witchcraft…

Over the years, Formula 1 rules have changed to restrict the speed at which cars can travel and corner, but driving one remains among the most remarkable of experiences.

Coulthard said: ‘All of your senses are heightened to the point where you’re at maximum fight-or-flight mode, in order to get the best out of yourself.

‘You are totally focussed on the moment. You’ve got stacks of information pumped away in your cerebellum, and you’ve got age and experience and what have you.

‘You’re making decisions based on the feel through the seat of your pants, vibration through your back, noise through your ears, feeling through your hands, everything is to the point where the car is an extension of your body. You intimately know your car.

‘The reality is – you’re living like a witch.’