Britain Before Brexit: an intimate portrait of the country and its people

Britain is divided, by twelve regions, a statistical arrangement designed to help governments see the life of the population in graphs, charts, and tables. I’m looking at Britain through these regions too, but not statistically; not through numbers that ignore the brilliant details of everyday life, but through the lens of my camera, on the ground, up close.

East of England

Luton greets me off the train with a megalomanic self-portrayal:

‘Opportunity. Aspiration. Prosperity. £1.5bn investment; 18 million passengers through the airport and further investment; increased connectivity by road, rail, and air; 10 new large businesses; five new hotels, a fit-for-purpose central rail station; a new skills and training programme for Luton residents; 5G and super fast broadband; 18,500 new jobs; 5,700 new homes; more residents connecting with their local councillors; town centre improvements; 5,000 families will be supported in parenting; return to work for 250 young people each year; investment in green travel; improved school results; 25 per cent increase in ‘early years’ learning; two new schools; fewer children under five with child protection plans; improved levels of mental wellbeing; 500 community volunteers in training and development opportunities; fully joined up health and social care services; Luton will be a dementia-friendly town; reduction in fly-tipping and other environmental crimes’.

I stand perplexed and re-read the text on the poster. Stalinist Five-Year Plan announcements come to mind, with their litanies of unachievable industrial and social advancements. I think too, of Winston Smith’s telescreen in George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, broadcasting an exaggerated list of achievements designed to cover up a less emphatically positive and progressive reality. Is this British propaganda in Luton? Political spin applied to urban planning? The same self-aggrandising, rose-tinted censorship for which the North Korean Ministry of Tourism is daily derided? In any case, when I walk into town, I am pleased not to find a utopia, but a town of positives and negatives, of charming imperfections, of intriguing contrasts and in-betweenness.

On the bus to Cambridge, I overhear two British university students describing how at school they had once been top of the class, had been major players in all areas, had been the best at many things, but now, at Cambridge University, they had become average, no longer influential, with only memories of past glories. I think this is an identity crisis common to Britain and the British, a deep-seated patriotic nostalgia stimulating the creation of such glorifying self-portrayals as Luton’s.

In a pub in Norwich, I ask a man at the bar what the best thing to do is in town. “Go back to where you came from”, he replies. This isn’t xenophobia, but an indulgent joy in hating the place where one is from, ironically, lovingly, as if it were a best friend whose company one pretends not to cherish. It strengthens the sense of belonging to the so-called “left-behind Britain”, where people say: “It’s bad, but it’s ours”, and where visitors are advised not to stay, because there’s “nothing to see and even less to do”. A lady tells me during the karaoke interval that she’d never do what I’m doing and travel around Britain. “Why not?”, I ask, “because it’s too familiar?”. ”No,” she answers, “because it’s crap”.

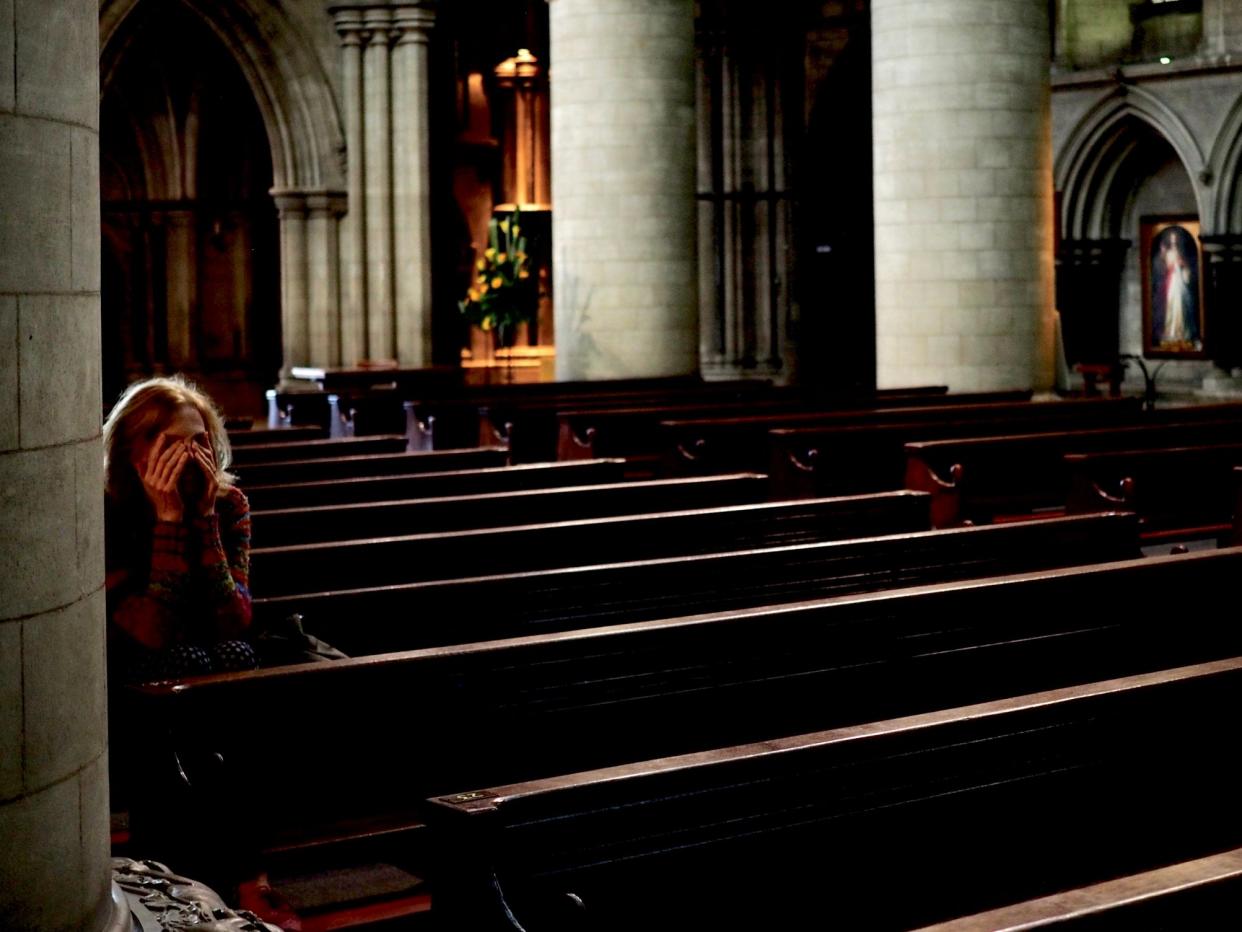

I wake up in Great Yarmouth and turn on Breakfast News. One of the presenters introduces the political editor from Brussels with: “We’ve been talking about Brexit now for what seems like forever. Seriously, can you tell us anything new this morning?” She’s right, I think. There’s so much talk about Britain and Britishness right now, in 2018, on the precipice of Brexit, but not a lot of looking. Of course, there’s Martin Parr and David Hurn and Simon Roberts and others, whose work is inspirational and poetic and important, but these photographers exist as a tiny minority in the face of a majority of voiced opinion. I get out of bed and turn off the TV. And as I walk out into the rain, over to Joyland, with its eye-bulging anthropomorphisms and end-of-season blues, across the sands to the Winter Gardens and Pleasure Beach, and finally, up to the front seat of a double-decker bus, getting a good view of Acle Straight’s eight-mile monotony stretching out before me across the moorland, I realise I’m happy to be looking at Britain, pleased to be thinking about Brexit outside the walls of the generic studio debate, a format that fails to show the theatre of Britain’s streets, their tragedies, ironies, chance moments of meaning, split-second dramas, and that cannot describe with its empty words and dry statistics the complex realities of Britain and its population, in its beauty, in its humour and sadness, in its contrasts, ambivalences and contradictions.

For more of Richard Morgan’s work you can visit his website here