Breaking Down Constitutional Originalism

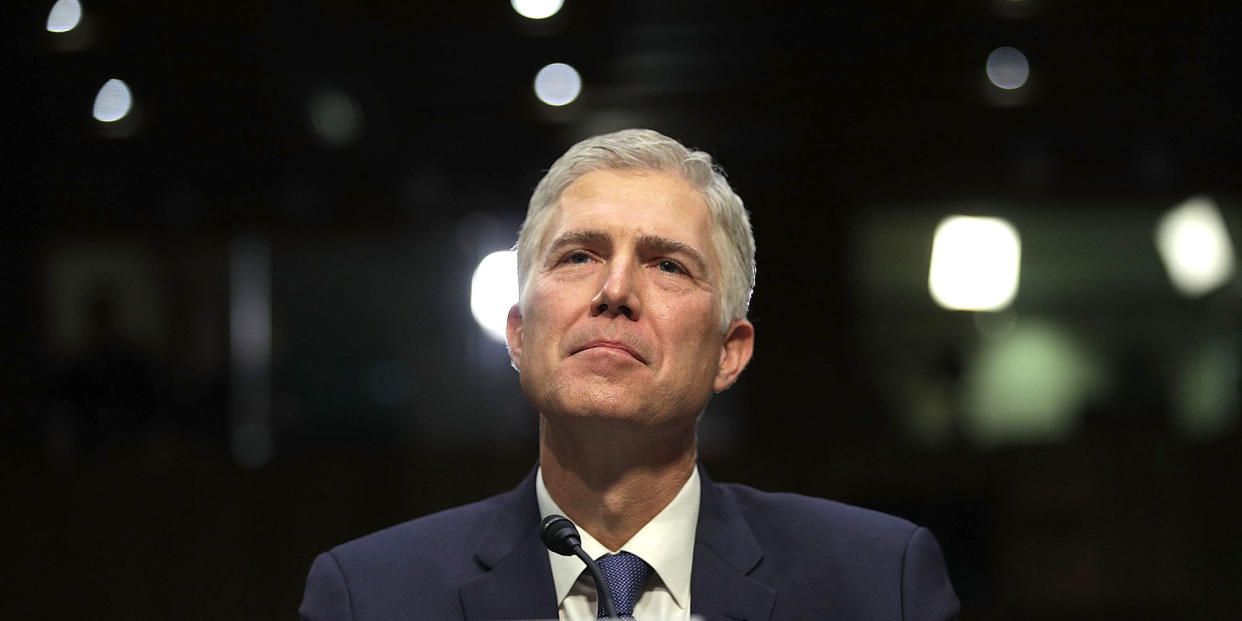

This week, Donald Trump's pick for the Supreme Court seat vacated by the late Antonin Scalia, Neil Gorsuch, started his Senate confirmation hearings. That Gorsuch is even being considered angers many Democrats, given that Republicans didn't extend the same courtesy to Merrick Garland, the moderate appeals court judge President Barack Obama nominated for the Supreme Court after Scalia's death, and whose nomination was summarily blocked by an obstinate GOP. In any event, Democrats now have to decide whether they block this nominee or hold their fire for the next, and presumably more radical, judge to come up for confirmation.

Part of the case for Gorsuch (or the case against him, depending on your view) is that he says he's a constitutional originalist, a legal ideology most closely identified with Scalia, the judge whose seat he may fill. Constitutional originalism is the theory that judges should interpret the Constitution as its authors meant it when they wrote it - that the Constitution is not a living, breathing document as more progressive legal scholars claim, but a black-and-white document to be read according to the literal text and what the writers meant when they penned it. It's a compelling vision, one that positions judges not as moral agents but simply neutral translators of the written word, seeking solely to carry out the law and not create it.

But it's also a false one - a role that is both impossible and undercut by its own conceit, given that the writers of the Constitution arguably intended for it to be a living document. And yet Gorsuch remains a proponent. Here's why his originalist theory is bullshit.

1. No one is really an originalist.

No, not even Scalia, who decided plenty of cases according to his own whims and opinions. Take the District of Columbia v. Heller case, about a D.C. law restricting handgun ownership. Until recently, judges generally interpreted the Second Amendment according to the same narrow interpretation many historians say the founders held, as evidenced by the text itself: that the Second Amendment doesn't give individuals the right to bear arms, but rather provides for the right of well-regulated militia to exist. There’s also significant historical evidence that the framers didn’t intend to protect individual rights to bear arms - when the Constitution was being created, several states proposed language that would have done just that, and they were rejected by the framers in favor of the militia language of the Second Amendment. Nor, of course, did the semi-automatic handguns at issue in the Heller case exist in the 18th century. But the “originalists” on the Supreme Court nevertheless interpreted the Second Amendment as protecting an individual right to handgun ownership, flying in the face of the text itself and the founders’ intentions. The same issue has come up in cases relating to corporate speech in the form of political donations - when the founders penned the First Amendment, did they really intend for corporate entities to be deemed “people” under the law, and for the First Amendment’s broad protections of speech to encompass a corporation’s unfettered ability to give money to politicians? Never mind; originalists say their impartial reading of the text and history of the Constitution is right, and the more liberal legal minds who also say they are impartially reading the text and history are wrong. It turns out people disagree about the precise meaning of words and sentences, and history is not clear on exactly how the founding fathers believed their words should be applied to conflicts and circumstances they couldn't even imagine. It also turns out even judges will twist and shape-shift their allegedly consistent legal philosophies to get the outcome they want.

2. Societies evolve, and that's a good thing.

And our laws should reflect that evolution. Our understanding of human rights has gotten more sophisticated; so has the science on how we live, experience pain, and develop. The knowledge that the human brain isn’t fully developed in teenagers, for example, wasn’t around when the authors of the Constitution prohibited “cruel and unusual punishment,” nor was there the same understanding we have now about intellectual disabilities. That information has impacted court decisions on capital punishment, as it should. And eventually, many progressive lawyers hope, our evolving human rights norms will put America in line with the rest of the developed world in outlawing capital punishment entirely.

3. Words evolve to reflect changing norms.

Terms that are linchpins of constitutional interpretation - “equal,” “cruel and unusual,” “unreasonable search and seizure” - didn’t mean the same thing in the 1790s as they mean now. Do we really want jurists to interpret “equal” the way it was meant when the Declaration of Independence declared that “all men are created equal” - excluding all women and men who weren’t white? As societies change, words do too, sometimes expanding and sometimes sharpening into focus. Figuring out what the framers meant is important, but 18th-century definitions of “equal” or “cruel” shouldn’t dictate 21st-century norms.

4. Technology evolves, and the law has to keep up.

Take the Fourth Amendment, which guarantees “[t]he right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures” without a proper warrant and probable cause. Under a strict textual reading, would the Fourth Amendment apply to cars, which the founders didn’t have? What about to government wiretaps of personal telephones, which also didn’t exist when the Constitution was ratified? A strict reading would allow broad government surveillance and the exact kind of tyranny the founders were trying to block. But unless the understanding of the text keeps pace with rapidly changing technology and innovation, the words and intentions of the Constitution will become obsolete, and we will all be worse off.

5. Originalism is a cover for legal discrimination.

Originally, people who were not white, Christian, land-owning men were not treated particularly well in the United States, and were not granted a full set of rights and liberties. A strictly textual reading of a law isn’t neutral; it also invites in the reader’s own biases and assumptions. And when that reader is looking to the historical record for the original meaning, well, a lot of our laws originally allowed a lot of terrible acts. Take the 14th Amendment, which was penned after the Civil War and provides for equal rights and protections under the law. The 1896 case Plessy v. Ferguson addressed the question of whether the equality promised by that Amendment prohibited segregation, and the Supreme Court found that it did not - that “separate but equal” was still equal, and permissible. It wasn’t until a half-century later, in Brown v. Board of Education, that the Court reversed itself, in a decision that was notably based not just on the text of the 14th Amendment itself, but also a showing that conditions for African-Americans were not equal to those of whites under Jim Crow, and that this inequality had starkly negative psychological and social impacts on black children. The words of the text didn’t change, but the Court’s - and society’s - understanding of “unequal” did.

6. Not even the founders were originalists.

If originalist judges want to follow the word and intent of the founding fathers, then they should trash originalism as a concept. The framers of the Constitution didn’t offer any instructions for how to interpret the document, nor did they get into specifics on what each of its provisions meant. Instead, they proffered broad concepts that, two centuries later, remain broadly applicable. This was a prescient decision, and one reason the United States is the oldest constitutional democracy in the world - precisely because our founding principles are sacred but nimble, and not constrained to a particular time period.

7. The founders weren’t fortune tellers and couldn’t predict every possible legal issue.

Many of the realities of modern life didn’t exist in the 18th century and nor were the founders capable of foreseeing every possible rights violation. If you’re a strict originalist - which in reality not even self-identified originalist judges really are - then it follows that if the founders didn’t specifically bar the government from doing something, the government is free to do it. This, of course, would be disastrous - what would block the government from imposing a China-style one-child policy or mandating sterilization of all men caught possessing marijuana?

8. No one really wants to live in an originalist country.

An originalist America is a worse America. Erwin Chemerinsky, the dean of the UC Irvine School of Law, puts it best:

Never in American history, thankfully, have a majority of the justices accepted originalism. If that were to happen, there would be a radical change in constitutional law. No longer would the Bill of Rights apply to state and local governments. No longer would there be protection of rights not mentioned in the text of the Constitution, such as the right to travel, freedom of association, and the right to privacy. This would mean the end of constitutional protection for liberties such as the right to marry, the right to procreate, the right to custody of one’s children, the right to keep the family together, the right of parents to control the upbringing of their children, the right to purchase and use contraceptives, the right to abortion, the right to refuse medical care, the right to engage in private consensual homosexual activity. No longer would women be protected from discrimination under equal protection.

And yet that’s the reality of originalism.

9. A Constitution that doesn’t reflect changing norms and realities is a Constitution that would eventually prove itself ineffectual and irrelevant.

Had the framers of the Constitution created a rigid, dead document, the American project may very well have failed. The judicial system is one crucial piece in our balance of powers, and if it’s a neutered body only capable of addressing the country like it’s still 1789 and we live in a country of farmers and slaveholders, it will simply be incapable of carrying out its role checking and balancing the modernized legislative and executive branches.

Of course the Constitution should be interpreted as it’s written. But “originalism” is a farce, something no judge in American history has adhered to - including the theory’s biggest proponents. Instead, it’s a rational-sounding cover for a more insidious set of right-wing beliefs, a way to allow rampant discrimination against actual people while protecting the interests of corporate “persons” and promoting the extreme ideologies of lobby groups. It’s a philosophy that deserves no place on today’s court.

Correction: A previous version of this article said handguns didn’t exist in the 18th century. The author was referring to the type of modern handguns at issue in the Heller case; however, this was unclear and has been clarified.

Follow Jill on Twitter.

You Might Also Like