Boynton Beach cemetery buried a stranger in their family plot, couple says in lawsuit

A family plot at Eternal Light Memorial Gardens in Boynton Beach has a stranger buried in it.

While not the fault of the soul trying to rest in peace, the cemetery double sold the space and must move the remains, Stanton Schwartz and his wife Susan Gad Schwartz say in a lawsuit.

Eternal Light wants to resolve the dispute “amicably” and has offered Stanton Schwartz another grave site, but the couple rejected that idea. After all, they purchased four adjacent plots in order to be together with her deceased parents as they were in life, and to honor a pact that they be buried side by side.

“I should not be in this terrible position where my wish to be buried together with my husband and my parents has been destroyed,” Susan Schwartz said.

Her husband’s plot is the one occupied by someone else, whom the cemetery won’t identify due to its policy that “all client information remains confidential,” said Claire Piché, area managing partner for operations at Eternal Light.

“This is a very sensitive matter, and all this anguish could have been avoided had Eternal Light lived up to its motto of ‘service you can trust,’” said Stanton Schwartz, 76.

“In direct contravention of these final arrangements and Plaintiffs’ ownership rights,” according to the lawsuit, Eternal Light violated the Florida Funeral, Cemetery and Consumer Services Act and “permitted the unauthorized remains to be interred in Mr. Schwartz’ grave space. This wrongdoing was concealed by Defendant, who had knowledge but failed to promptly notify all interested parties despite its legal obligations.”

The Schwartzes noticed something awry during one of their visits to the grave of her parents, Joseph and Evelyn Greenblatt. Her father died in 2016 at age 96 and her mother died in 2008. Their gravestone, which reads “Your life gave us meaning,” sits next to a bench inscribed with the Greenblatt name.

When the couple inquired at the cemetery office, an employee pulled out a map, searched records and assured them their two plots had not been disturbed. But when friends of the family visited weeks later, and also became suspicious, they were told Stanton Schwartz’s plot, purchased for $6,415 in 2007, had been double sold. And had a coffin in it.

“This is the type of business where you have to do it right the first time because burial is a very emotional subject,” said Cristina Pierson, the Schwartzes’ attorney. “It’s not like, sorry, I sold you the wrong Toyota.”

Eternal Light’s offer to give Stanton Schwartz a plot elsewhere “requires too much sacrifice from the family,” Pierson said. The cemetery does not want to move the remains already in Schwartz’s space because under Jewish law disinterment disturbs the soul, exposes the body and is disrespectful to neighboring corpses.

“I believe the cemetery does not want to create another problem, but unfortunately they’ve already created a big one,” Pierson said.

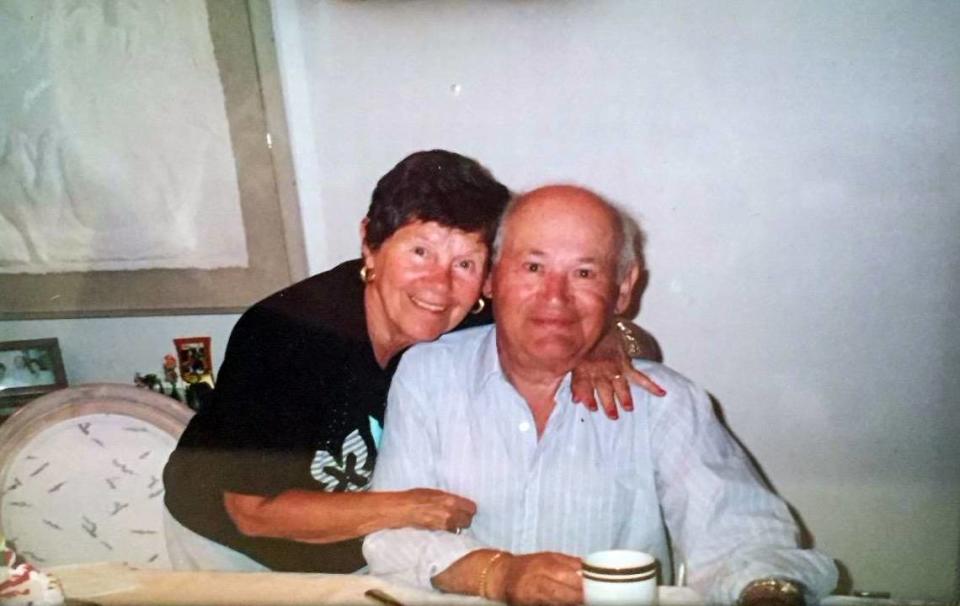

Holocaust survivors

Stanton and Susan Schwartz were exceptionally close to her parents, who were Holocaust survivors. The two couples lived next door to each other in Lake Worth, and when Evelyn Greenblatt died, Joseph Greenblatt moved in with his daughter and son-in-law.

They vowed to be buried together. So many relatives had died during World War II and were never found. Jewish law requires that all parts of the body, no matter what its state, be buried together.

“This was greatly important to all of them because Evelyn and Joseph were Holocaust survivors and most of their family members perished under dire circumstances without a final resting place and without the ability to be buried with family,” the lawsuit states.

Pierson typically works on commercial litigation and class action suits for her firm, Kelley Uustal. She took the Schwartz case not only because she found it “heartbreaking,” but because she is intent on finding out if there are other examples of double sold plots.

In a notorious cemetery scandal, Menorah Gardens and its parent company, Houston-based Service Corporation International, were sued in 2001 for overselling space and mishandling hundreds of bodies at crowded cemeteries in Palm Beach and Broward counties.

Relatives complained that bodies were buried in the wrong places or stacked to make more room; husbands were separated from wives; vaults were cracked open by a backhoe; remains were exhumed, and bones, skulls and shrouds were thrown into the woods.

A settlement required the company to pay $100 million in damages to 350 families and repair and reorganize graves. The cemeteries were reconsecrated under the direction of rabbis in 2008 and 2011, but some families said they would never know for certain if their loved ones were buried where they were supposed to be.