BOSH Project restores sagebrush sea at a grand scale in southwest Idaho

Habitat improvements made possible by the BOSH Project will benefit sage grouse, song birds, small mammals and spotted frogs, among other species. (Photo courtesy of Ken Miracle)

This story was first published by Life on the Range.

In the spring of 2023, Bureau of Land Management fire crews burned juniper trees – cut in 2021 – to restore the sage-steppe landscape in the huge expanse of Owyhee County in southwest Idaho.

The spring burning projects are a key part of the Bruneau Owyhee Sage Grouse Habitat project, known as BOSH for short. A collaborative partnership of state and federal agencies, wildlife advocacy groups and private landowners seek to restore the native upland landscapes to a more natural condition – benefitting sage grouse, songbirds, antelope, spotted frogs and other wildlife.

The BOSH project is unprecedented in scope and scale – 30,000 acres of state and federal lands are being treated per year to halt juniper encroachment. In the sixth year of the project, 140,000 acres have been treated so far.

New scientific research has shown that conifer encroachment is the No. 2 threat to sagebrush ecosystems, just behind the threat of invasive annual plants like cheatgrass.

When junipers take over the landscape, other native plants suffer, studies show. Pre-treatment, lost production of herbaceous production peaked at 14,030 tons in 2016, according to Yield Gap data produced by the University of Montana. Over the last 30 years, 104,742 tons of herbaceous production have been lost to juniper encroachment in the BOSH project area, according to Yield Gap data.

This photo shows Idaho meadow and upland habitat restored post-treatment. (Photo courtesy Connor White)

However, the land bounces back quickly following treatments – an increase of 5,000 tons of herbaceous production occurs per year, according to Yield Gap data.

“We’ve been taking a lot of photo points, post-treatment, springs, seeps, riparian areas to document the changes,” said Chris Yarbrough, habitat biologist for Idaho Department of Fish and Game. “Once trees have been removed, old seeps come back to life. Which is a fantastic benefit to wildlife, not just grouse but big game, Columbia spotted frogs, and a whole bunch of other critters.”

BOSH project could be single-largest restoration effort Working Lands for Wildlife has undertaken in sagebrush biome

Treatment plans are strategic: All of the juniper cutting units are within 10 kilometers of 70 sage grouse leks in the 617,000-acre project area.

The value of improving sage-steppe habitat for sage grouse and other critters inspired the BOSH team to go big.

“The BOSH project stands to be the largest single restoration effort we’ve ever undertaken in the sagebrush biome. Just to put this in context, it’s probably five-to-six times larger than any similar area we’ve undertaken to address this conifer issue,” said Jeremy Maestas, national sagebrush ecosystem specialist for Working Lands for Wildlife.

“When we take that bird’s eye view of the whole biome, the southwest portion of Idaho and the BOSH project is the bull’s eye, ground zero for some of the best sage grouse ecosystems that we have.”

Juniper trees have been encroaching on the sage-steppe landscape for decades, crowding out native vegetation, drying up seeps and springs, and sapping the productivity of the land.

“It simply outcompetes all other vegetation. They also suck out the available water. The juniper will eventually win,” said Connor White, BOSH Project manager for Pheasants Forever and the BLM.

University of Montana scientists matched aerial photography from 1950 with present-day in the Owyhees, showing the spread of junipers on the landscape.

Connor White, project manager for Pheasants Forever and the BLM (Courtesy of Life on the Range)

“Juniper management is a way to keep the sagebrush-steppe healthy,” White says. “The reason we’re seeing all of this juniper encroachment is because we’ve taken a lot of fire out of the system. Juniper is a native tree; it belongs out here on this landscape. Through our own actions, since we settled the West, namely fire suppression, we’ve had an incredible increase in junipers on the landscape. Anywhere from 125-625% increase, across the West as a whole.”

“So we’re mimicking fire by using mechanical cutting,” White adds.

In the Warner Mountains of eastern Oregon, following juniper removal, researchers documented a 12% increase in the growth rate for sage grouse populations. High-quality habitat increased by six times. A similar response is expected in the Owyhees.

“For the first time ever, we actually documented a population-level response by sage grouse to restoration actions,” Maestas says.

A strong partnership of 10 state and federal agencies, wildlife conservation groups and private landowners are working together to support the project. Treatments transcend land management boundaries using the All Hands, All Lands approach.

The partners collectively fund the project at a cost of $1 million to $2 million per year.

To oversee the project, project partners hired White to coordinate activities. White is an avid hunter and wildlife professional for Pheasants Forever.

Conifer control projects initially started in 2010 on private lands in the West, with funding from NRCS Working Lands for Wildlife. The projects benefitted sage grouse and livestock.

In 2013, the Life on the Range crew did a video documentary on a project in the Owyhees featuring local ranchers and Art Talsma (now retired) from the Nature Conservancy.

The intrusion of juniper trees into meadow and valley areas have had a direct negative impact on sage-grouse nesting habitat and brood-rearing habitat, Talsma says.

“The leks tell you where the sage-grouse want to be,” he says. “The bird wants to find a nest within one or two miles of the dancing ground where reproduction takes place. They look for sagebrush or bitterbrush habitat, and that’s where they will hide their nest. But they will not select the site at all if there’s a tall juniper tree there. So as juniper encroach on a meadow, the sage-grouse have to vacate it — they flat-out won’t stay there.”

The control method? Contractors used masticators to grind up juniper trees. That worked well at a small-scale.

Water sources, springs and seeps come back to life after conifer-removal in sagebrush biomes occur. (Courtesy of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

Jordan Valley Rancher Dennis Stanford liked the results.

“It’s a big help. It brings up the water table for one thing,” he says. “When you kill a juniper tree, you’re taking away something that’s wicking the moisture away from the sagebrush, forbs, grasses and everything else. So it’s a win-win situation. It’s more forage for the cows and better wildlife habitat for all wildlife.”

Following juniper control efforts, the number of male sage grouse have doubled on leks two to three years after treatment. Talsma expected similar results to occur in Wilson Meadow on Stanford’s land.

“We find out from talking to the ranchers that the birds have been coming to this site for years,” he says. “Nearby here, we surveyed a site that had over 200 birds in the fall. And that’s just 3-4 miles from here. So we know, when we open it up, we’ll get the bird use back.”

Crews work year-round on project in the Owyhees

Over the last decade, NRCS has worked with more than 2,000 landowners across the West to improve sage grouse habitat on 700,000 acres of land.

Today, conifer-treatment projects are being done at a much larger scale – on public lands as well as private lands.

To treat 30,000 acres per year in the Owyhees, crews work year-round to stay on course.

In the spring, once the junipers dry out, BLM crews fan out to burn downed trees cut in the previous 18 months. The timing is crucial so the dead junipers burn, but the sage brush doesn’t.

“Conditions today are ideal,” White says. “We’ve got about 50 degrees, light breeze, and relative humidity is right where we want it. The brush is not receptive to fire, but the fuels are, so it’s ideal conditions.”

The burning activity invigorates the soil and accelerates the return of native grasses to the landscape. The new regrowth benefits the land and many species of wildlife.

In the summer, chainsaw crews move into the country to cut junipers.

Hiking through the sagebrush, the crew drops juniper trees as they go.

“Right now, as of today, we’ve got 50 chainsaws running between the BLM cutting and the stuff on the private, so they’re pretty well dialed at this point and everything is looking really good,” White says.

Each member of the crew packs water bottles, chainsaw fuel, bar chain oil and blade-sharpeners so they can stay on the move.

Crew boss Juan Salazar-Sanchez says they enjoy the work. “Yeah, I like it. I’ve been doing this all my life.”

How many acres do they cover in a day?

“All depends on how many trees we have per acre,” he says. “Sometimes we can cover an acre in an hour, sometimes 25 acres in eight hours. In one area by Oreana, it was only nine acres, but it took us 190 hours to get it done. That was so many!”

The crew, based in Bend, Oregon, works 7.5 hours a day and camps overnight near cutting units to stay close to the job. They make $22-$23 an hour. “Yep, it pays the bills,” Salazar-Sanchez says.

White works with the crews to make sure they meet the proper standards for dropping and limbing trees so predators can’t perch on the limbs.

“We try to be out here a couple of times a week, so we invest a lot of staff time to make sure they’re following contract specifications, and that’s on us to make sure they’re doing that,” White says.

Crews learn to protect old-growth junipers

One important aspect: Crews are trained how to identify old-growth juniper trees, which are left in place.

“One of the things when we’re out here cutting junipers at a landscape scale, we don’t want to cut the old-growth,” notes Lance Okeson, manager of the BLM Fuels Program. “That’s the treatment parameters, cut the younger trees, and leave the old growth.”

BLM Fuels Program Manager Lance Okeson explains the characteristics of an old-growth juniper tree. Chainsaw crews leave the old-growth trees in place. (Courtesy of Life on the Range)

White and Okeson educate crews to look at the tree’s shape, bark, moss, lichen and location to determine if it’s an old-growth tree.

“Size doesn’t have anything to do with it. It’s about all of those characteristics and having them present on a tree that we would call it an old-growth tree,” Okeson says.

When things cool off in the fall, the BLM burns junipers under the right weather conditions to remove trees and eliminate the fire hazard. A heavy equipment operator stacks the trees into large piles next to public roads, and BLM crews burns the piles. They do this in the winter, too.

White explains it’s important to remove the fuel hazards next to public roads in the Owyhees because during the hot summer months, a wildfire could break out, and those roads would need to be used as fire breaks. They do the jackpot burns 200 feet on either side of the roads.

“So if we come in under conditions like we’ve got today, and do some burning, we’ve just set them up to have a much greater chance of success, when that wildfire occurs,” White says. “Managing the fuel break essentially, managing the fuels.”

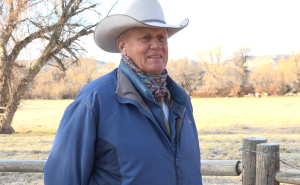

Ranchers are supportive of the project as well. Chuck Hall treated his mountain property in the Owyhees.

Bruneau rancher Chuck Hall (Courtesy of Life on the Range)

“Properties like that don’t come up very often. In ’07, I bought it. It’s been my happy place to go,” Hall says. “It’s a great place to have peace of mind, raise cattle, just enjoy life mostly, I’ve really enjoyed it. It’s always 10 degrees cooler than it is down here.”

Hall sees a lot of sage grouse on his land.

“My places was chicken capital in that whole country. In July and August, they’d flock into the water and they’d hang out around the house even,” he says.

Hall treated junipers on his property 3-4 years ago and liked the results.

“I cut about 75 big trees, and within a week, 10 days, the spring came back. It always ran, but it ran twice as much or more than it did,” he says. “Those trees sucked up a lot of water. It made a big difference.”

Hall sees a lot of benefits for ranchers and wildlife.

“That’s a godsend for us cowboys,” he says. “We’re going to have more water, more grass; it’s going to take some time, but I’m quite certain it’s worth it.”

White is happy with the results so far. He peers off in the distance, looking into the vast open spaces of the Owyhees, with South Mountain off in the distance.

“Since sage grouse are a landscape-level species, we have to design conifer treatments that are also at a landscape scale,” White says. “So everything behind me, from here to there (motions with his arms) was treated in 2020 or 2022. Thousands and thousands of acres. Like we like to say in our shop, horizon to horizon.”

“We’ve learned over time that it’s much more effective to go where grouse still remain, and grow those core areas through this restoration practice,” Maestas, the national sagebrush expert, says. “We’re seeing an immediate response in a lot of projects where grouse will show up literally following the equipment as we remove trees from the landscape. It’s like instant habitat creation.”

“Overall, we’re thrilled with the results,” says Yarbrough with Idaho Fish and Game. “The scale at which these acres are being improved is nothing that’s been done before in this country, so it’s been really neat to see all the partners coming together and tackle this issue of encroaching conifers. That has been awesome to see.”

End note: The public is welcome to cut juniper trees for firewood in the Owyhee project area. Contact the BLM Owyhee Field Office in Marsing or the BLM Boise District to obtain a firewood permit.

Steve Stuebner is the writer and producer of Life on the Range, a public education project sponsored by the Idaho Rangeland Resources Commission.

The post BOSH Project restores sagebrush sea at a grand scale in southwest Idaho appeared first on Idaho Capital Sun.